CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU |

DECEMBER 2021

Data Point: Checking

Account Overdraft at

Financial Institutions

Served by Core Processors

Data Point No. 2021

-11

Nicole Kelly and

Éva Nagypál, Ph.D.

1

Table of contents

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 2

2. Data ........................................................................................................................ 7

3. Overdraft policies ............................................................................................... 14

3.1 Overdraft programs .................................................................................15

3.2 Opt-in ....................................................................................................... 17

3.3 Fee waiver policies .................................................................................. 20

3.4 Decisioning policies ................................................................................ 23

3.5 Transaction posting order ...................................................................... 29

4. Overdraft and NSF revenue ............................................................................... 35

4.1 Overdraft fees, incidence, and revenue .................................................. 36

4.2 NSF fees and revenue ............................................................................. 42

4.3 Sustained negative balance fee revenue ................................................. 45

5. Linked accounts ................................................................................................. 47

6. Appendix A: Information Request ..................................................................... 48

7. Appendix B: Comparing credit unions using varying processing

solutions .............................................................................................................. 61

2

1. Introduction and Summary

This Data Point describes practices and outcomes at several thousand credit unions and banks

in 2014 regarding the payment of debit transactions

1

that exceed a consumer’s account balance

(commonly known as “overdraft”).

2

While the data underlying the report are from a few years

ago and may not always reflect current practices and outcomes, to our knowledge, these are the

most detailed and wide-ranging quantitative data the Bureau or others have collected on

overdraft practices at small institutions.

This publication complements earlier publications produced by the Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau (“Bureau”) about consumer checking account overdraft programs. A large

part of our 2013 White Paper

3

and our 2014 and 2017 Data Points

4

focused on overdraft

practices and outcomes at a number of large banks (“large study banks”) under the Bureau’s

supervisory authority.

5

Those publications summarized aggregated and anonymized

transaction-level data from the large study banks.

6

In contrast, the vast majority of financial

institutions (FIs) covered in this Data Point have assets under $10 billion.

In order to understand and assess risks and benefits to consumers from overdraft programs, the

Bureau studied how the policies that influence consumer outcomes related to overdraft vary

across the broader market, including at FIs with assets under $10 billion. Given the large

number of smaller institutions (of the over 12,000 FIs in the United States, more than 99% had

1

A debit transaction is any transaction that, if paid, decreases a checking account’s balance.

2

Alternatively, a financial institution may decline the debit transaction or return it unpaid due to non-sufficient

funds.

3

CFPB, 2013, “CFPB Study of Overdraft Programs: A White Paper of Initial Data Findings”.

4

Trevor Bakker, Nicole Kelly, Jesse Leary, Éva Nagypál, 2014, “Checking Account Overdraft,” CFPB Data Point; and

David Low, Éva Nagypál, Leslie Parrish, Akaki Skhirtladze, Corey Stone, 2017, “Frequent Overdrafters,” CFPB Data

Point.

5

The Bureau has supervisory authority over large banks and credit unions with assets over $10 billion, as well as their

affiliates. See 12 U.S.C. § 5515(a).

6

Those data cover the January 2011 through June 2012 time period. Note when comparing the findings of those

publications to this Data Point that the data in this report cover a later time period. Also, there are differences

between the findings using the aggregated data in the 2013 White Paper and the transaction-level data in the 2014

and 2017 Data Points, partly due to metholodogical differences, such as the exclusion of inactive accounts.

3

assets under $10 billion during the period covered

7

), “core processors”

8

who offer deposit,

payment, and data processing services to these FIs were viewed to be uniquely positioned to

provide information efficiently and effectively on the overdraft programs of smaller FIs. In 2015,

the Bureau collected anonymous institution-level information from several core processors

about overdraft program configurations, fee revenue, and consumer overdraft use across credit

unions and banks of various asset sizes for a 12-month time period predominantly covering

2014. The data obtained informed us about overdraft at 3,904 FIs maintaining 30 million

consumer checking accounts. We generally refer to these FIs as the “core processor sample” and

the data collected about these FIs as “the dataset.” This report contains findings derived from

the core processor sample.

It should be noted that the findings presented in this Data Point are limited to the FIs whose

data were obtained in 2015 through our request to the core processors who used these

processors on an outsourced basis. While the sample represents 25.4% of credit unions and

58.0% of banks offering checking account services, it may not be representative of small

institutions overall. Moreover, the findings are based on information provided by the core

processors on how their services were configured at the direction of their client FIs. Thus, we are

not reporting information directly obtained from the FIs themselves.

Overall, we document substantial variation in the policies reported for the FIs in the core

processor sample. This variation notwithstanding, it is notable that on average FIs with an

overdraft program in the dataset derived similar amounts in annual overdraft revenue per

account as the large study banks examined in our earlier reports. Specific key findings from our

analysis are as follows:

9

Findings for the core processor sample:

In the dataset, nearly all (92.9%) of the banks had an overdraft program, while such

programs were less common among credit unions, with 60.9% of them having one.

7

National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) and Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Call

Reports, 2014 quarter 4.

8

Core processor companies provide operations and accounting systems to banks and credit unions. Among other

services, these systems generally perform deposit and payments processing and maintain account balances. Smaller

FIs generally find it more economical to use platforms developed by third parties, such as core processor

companies, bankers’ banks, correspondent banks, or corporate credit unions, than to develop their own systems.

9

Some of the terms used in this section may not be familiar to readers not acquainted with overdraft and transaction

processing. Definitions of all terms used and sources are provided in the main text.

4

Among FIs with an overdraft program, overdraft decisions were predominantly

automated.

FIs with an overdraft program often had policies in place to waive fees in certain

circumstances. For the observed banks, this was typically done by waiving fees when an

account was overdrawn by a small amount or the transaction overdrawing the account

was small (de minimis policies) or by having a daily cap on the number of fees that could

be incurred. For the observed credit unions, fee waivers were more commonly offered

through forgiveness periods during which consumers could deposit funds after an

overdraft transaction to avoid an overdraft fee.

Credit unions and banks in the dataset had a variety of decisioning policies that affected

overdraft. Specifically:

When deciding whether to authorize or decline an ATM or debit card transaction,

virtually all FIs in the dataset considered an account’s available balance. To

determine whether to pay or return a debit transaction that was not already

authorized, observed credit unions nearly uniformly (99.5%) used an account’s

available balance, while observed banks were somewhat split between using available

and ledger balance (45.2% vs. 54.8%). Correspondingly, virtually all observed credit

unions used available balance to determine whether to charge an overdraft or non-

sufficient funds (NSF) fee, while observed banks were split between using available

and ledger balance.

About a third of observed FIs made funds received through electronic direct deposit

available for a consumer’s use generally before the settlement date, with the share of

banks that did so increasing with asset size.

Over 90% of observed credit unions and over 60% of observed banks limited the

amount by which an account could be overdrawn, either with a common limit for any

eligible account or with a specific limit set for each account individually. The

prevalence of individualized limits increased with asset size.

Observed credit unions and banks also had a range of practices regarding the order in

which they posted transactions. This ordering may have impacted the number of

overdraft fees incurred if an account became overdrawn. Specifically,

Banks in the dataset predominantly processed a day’s transactions grouped by

transaction type after the close of business each day (“nightly batch processing”),

5

while credit unions in the dataset most often used a combination of intraday posting

and nightly batch processing. Correspondingly, credit unions in the dataset were

more likely to charge intraday overdraft fees.

While the posting of credits before debits was the prevalent practice among all

observed FIs, it was more common at banks than at credit unions in the dataset.

Almost two-thirds of observed credit unions but less than a quarter of observed

banks posted debits chronologically when transaction timestamps were available.

Ordering transactions by size was more common among banks in the dataset than

among credit unions. Observed banks that ordered transactions by size were nearly

evenly split between those that ordered largest to smallest and those that ordered

smallest to largest.

Most observed FIs with an overdraft program offered consumers the option to link their

checking account to a savings or credit account to cover transactions that would

otherwise result in a negative balance. The data received from the core processors

indicate that the share of consumers linking their checking account to either a savings or

a credit account at the observed banks and the share of consumers linking to a credit

account at the observed credit unions was generally under 10%. However, about 70% of

checking accounts at the credit unions in the sample were linked to savings accounts.

Findings with comparison to large bank practices and outcomes:

Consumers could opt in per Regulation E to accept overdraft fees on automated teller

machine (ATM) and one-time debit card transations at about two-thirds of observed FIs

with an overdraft program. The share of consumer checking accounts in our dataset

identified to have opted in at the FIs with this option was 29.9% at credit unions and

20.2% at banks. In comparison, the share of checking accounts opted in at the large

study banks offering this option was 19.4%.

10

Per-item overdraft fees at the FIs in the dataset were lower than the average overdraft fee

among 44 of the nation’s 50 largest banks during the same time period ($34.05), with an

average fee of $27.64 at observed credit unions and $29.55 at observed banks.

10

As noted in Footnote 6, the data for the large study banks and for the core processor sample cover different time

periods, so they are not exactly comparable.

6

The distribution of the annual number of overdraft fees across consumers at the FIs

served by the core processors was similar to that at the large study banks: overdraft fees

were concentrated among a relatively small share of accounts that incur over 10 fees in a

year (3.2% and 2.4% at the observed credit unions and banks versus 2.9% at the large

study banks).

Credit unions with an overdraft program in the dataset earned $42.33 in annual

overdraft revenue per account on average, while the average annual overdraft revenue

per account earned by banks with an overdraft program in the dataset was $40.37. By

comparison, annual overdraft revenue per account at the large study banks (that all have

overdraft programs) before and after the application of manual waivers was $45.21 and

$41.47, respectively.

Both the incidence of overdraft and overdraft revenues per account largely varied by

whether the FI had opt-in, with those that had opt-in charging a higher number of

overdraft fees and collecting more in overdraft revenues per account.

Nearly all FIs in the dataset charged per-item NSF fees if they returned transactions due

to non-sufficient funds in a consumer’s bank account. Typically, these fees were reported

to be the same as the per-item overdraft fee charged at a given FI. Annual NSF revenue

per account was reported in the dataset as $17.05 for credit unions with an overdraft

program and $9.73 for banks with an overdraft program, compared to $13.27 at the large

study banks.

Nearly three-fifths of banks and about one-fifth of credit unions in the dataset charged

sustained negative balance fees when an account remained overdrawn for a specified

period of time. Annual revenue per account from these fees across FIs with an overdraft

program that charge such fees in the dataset was $1.77 at observed credit unions and

$4.30 at observed banks, compared to $6.30 at the large study banks.

The following section provides a description of the data used to derive these results, and the

remaining sections outline these findings in greater detail.

7

2. Data

Core processors provide deposit, payment, and data processing services to FIs. FIs that use core

processors can generally configure the core processor software to reflect their policy and

processing preferences. Thus, the settings reported by the core processors in our surveys

indicate FI processing choices and generally provide an indication of the FI’s policies.

In 2015 the Bureau obtained information from core processors regarding these software settings

for 4,091 FIs. These data provide insights regarding the overdraft practices and consumer

outcomes at these FIs for a 12-month period predominantly covering 2014.

11

The data collection

consisted of an information request, included as Appendix A to this Data Point, comprising

multiple-choice and numeric questions to core processing companies.

12

The survey asked how

individual FIs using core processors on an outsourced, online basis (also known as an

“application service provider” or ASP model) directed the processors to set configurations to

administer their checking accounts and their overdraft program, if any.

13

In addition, the core

processors were asked certain questions related to individual FI’s overdraft-related outcomes.

The core processors were not asked for and did not provide information that could be used to

identify individual FIs using publicly-available data. As a result, the data represent an

anonymous survey of the FI clients of the participating core processors.

It is important to note that the core processors in this study did not offer a single product;

rather, they each offered a collection of platforms. Combined, the core processors provided data

to the Bureau from a total of 26 platforms. These platforms varied significantly in size, with the

smallest serving very few FIs and the largest serving hundreds of FIs. Most platforms were

specialized by institution charter type: over two-thirds of the platforms served either just credit

unions or just banks. Functionality and capabilities varied across platforms. For example, a few

platforms didn’t have the functionality to offer Regulation E opt-in; however, this limitation did

11

The Bureau requested 12 full calendar months of data, if available. The earliest end of observation period was

October 2014 and the latest was June 2015.

12

The data for this report were obtained from core processors through a request pursuant to Section 1022(c)(1) &

(4)(B)(ii) of the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. For information about

privacy protections for these data, see the Bureau’s

“Market Analysis of Administrative Data Under Research

Authorities Privacy Impact Assessment.” Consistent with the Bureau’s rules, the data findings presented in this

report do not directly or indirectly identify the institutions or consumers involved. See 12 C.F.R. § 1070.41(c).

13

The core processors also sell their software to FIs that install and run it on the FI’s own systems. The core

processors could not provide any information about overdraft in these cases.

8

not preclude an individual FI from implementing an opt-in program through a separate third-

party arrangement or software. Readers should keep such differences in mind when looking at

the results.

Of the 4,091 FIs for which we received information, we excluded 187 due to a variety of issues

with the data we received.

14

Thus, this report analyzes the remaining 3,904 FIs. We refer to

these FIs as the “core processor sample” and the data collected about these FIs as “the dataset”

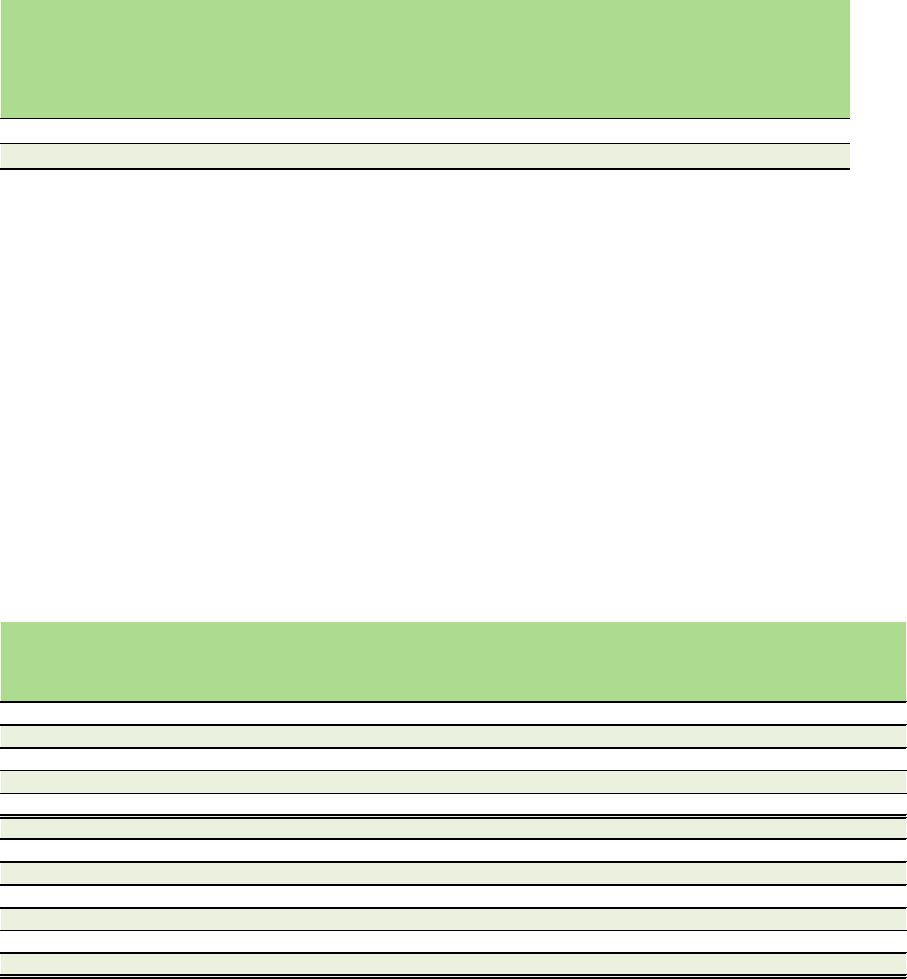

throughout this publication. Table 1 compares the distribution by asset tier of credit unions in

the core processor sample (which reports asset tier at a date at or very close to the end of 2014)

and those in the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) Call Reports at the end of 2014

(restricting to credit unions reporting share drafts, i.e., those offering checking account

services).

15

,

The core processor sample has a higher representation of credit unions with assets

under $100 million and does not include many of the larger credit unions with over $550

million in assets,

16

because, as we show in Appendix B, these larger credit unions were more

likely to license and run a core processor’s or other vendor’s software in house or use proprietary

solutions for their processing needs. Overall, the core processor sample captures 1,266 of the

4,979 credit unions offering checking account services at the end of 2014, 25.4% of the total.

14

Twenty-six FIs were excluded for not satisfying the inclusion criteria of being sizable, consumer-facing institutions

outsourcing to core processors (i.e., institutions with fewer than 10 consumer deposit accounts, brokerage or asset

management institutions, or institutions not receiving services on an outsourced basis were excluded). In addition,

89 FIs were excluded for having been in transition (converting to/from their respective platform, opening/closing,

or rapidly expanding or shrinking) since our questions were not designed to capture the dynamics of such

transitioning FIs, and 72 FIs were excluded due to the lack of information on critical variables (asset size or number

of accounts).

15

We used the public NCUA and FFIEC Call Report data files provided to us by SNL (www.snl.com). For both credit

unions and banks, the asset sizes (and later, revenue figures) in the core processor sample do not necessarily

correspond precisely to NCUA and FFIEC Call Report filings. This is for a number of reasons. First, the systems that

the core processors pull these measurements from are not necessarily the same ones used for filing Call Reports and

differences can exist due to accounting adjustments, differences in accounting periods, etc. Second, the core

processors’ relationships with FIs is at times at the individual institution level and at other times at the holding

company level so they may be reporting institution-level or holding company-level assets. The asset size from the

Call Report is institution-level asset size.

16

The size standards of the U.S. Small Business Administration indicate that banks and other depository institutions

may qualify as small businesses if they have $550 million or less in assets. See

https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/files/Size_Standards_Table.pdf

.

9

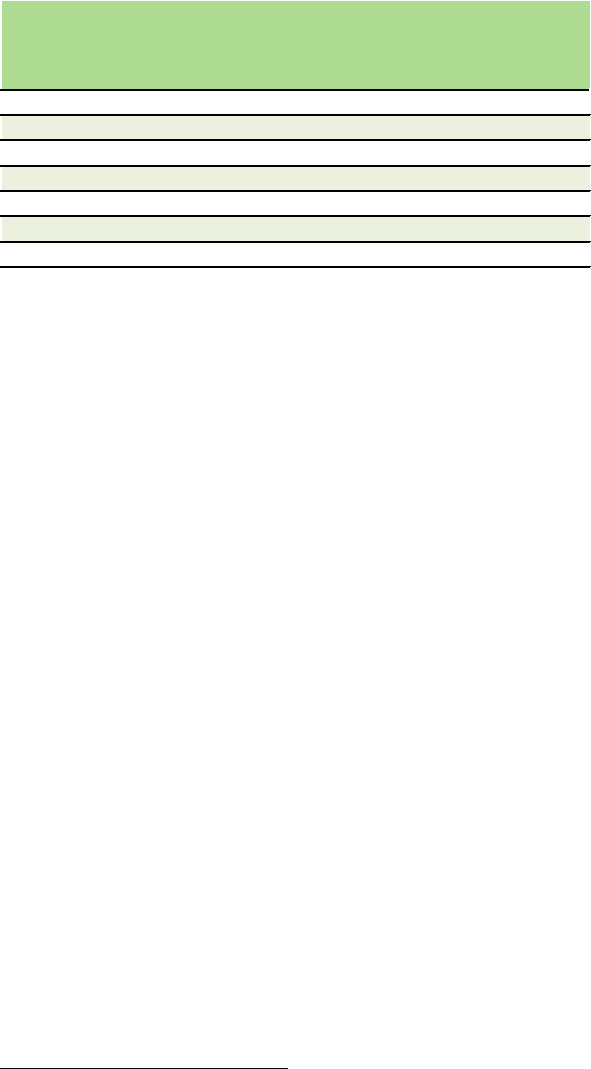

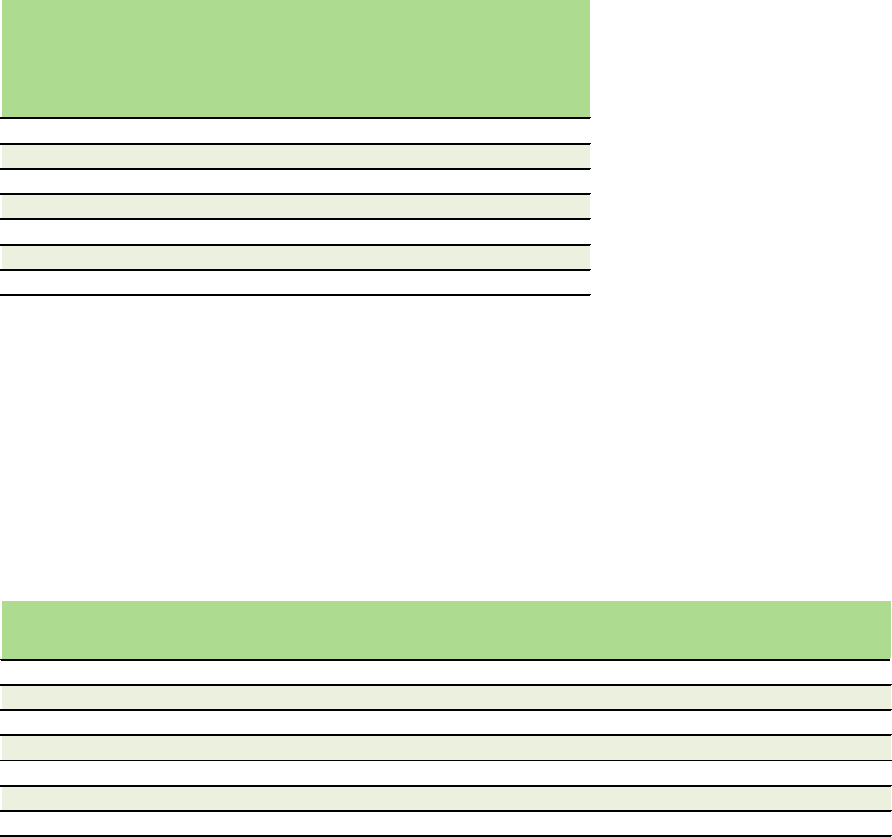

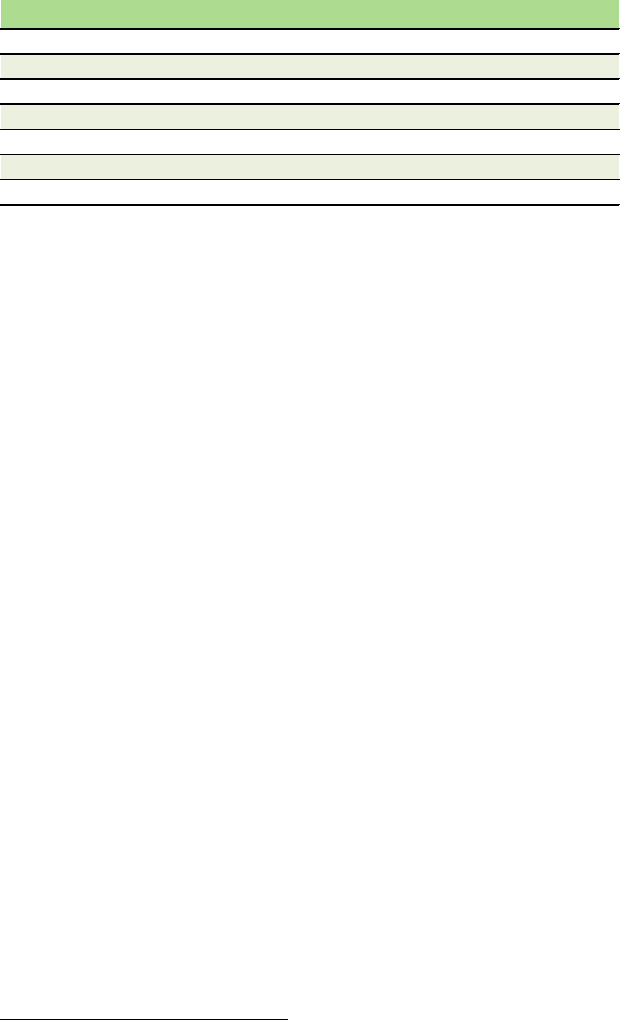

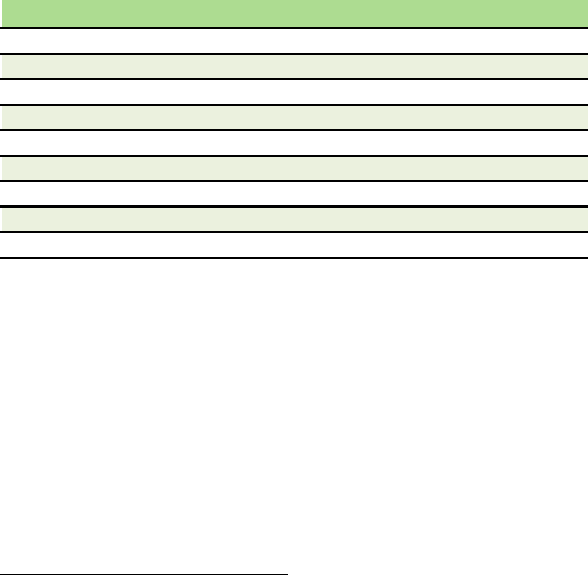

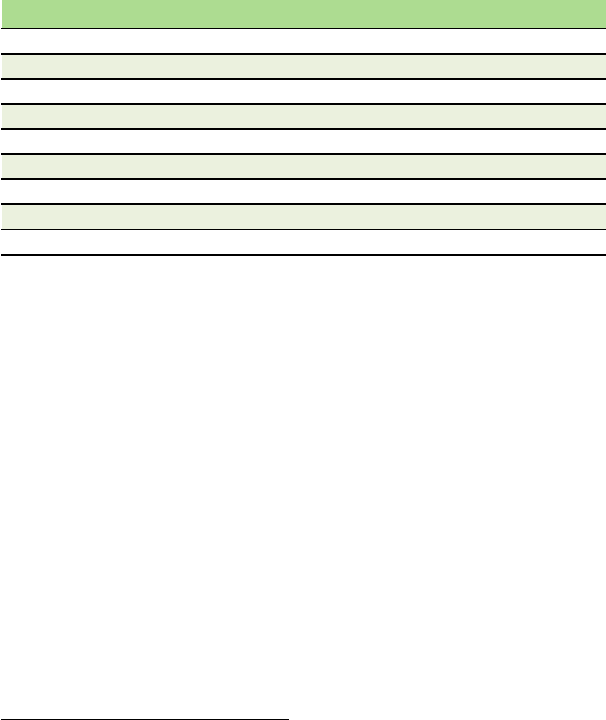

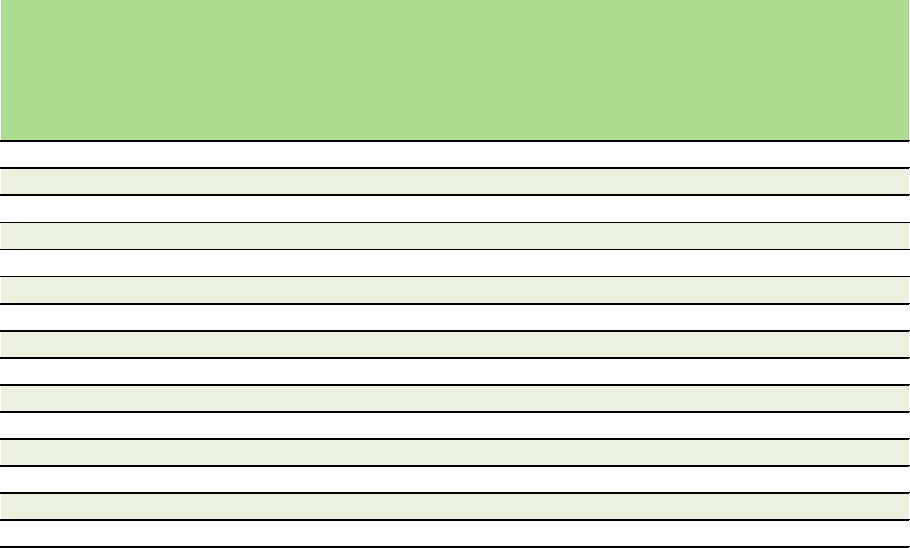

TABLE 1: DISTRIBUTION BY ASSET TIER OF CREDIT UNIONS IN THE CORE PROCESSOR SAMPLE

AND OF CREDIT UNIONS WITH SHARE DRAFTS IN THE 2014 CALL REPORT DATA

Asse t ti e r

Core processor

sa m pl e

NCUA Call Report

(credit unions

with share drafts)

$100M or less 80.4% 69.7%

$100M< to $550M 18.2% 22.0%

$550M< to $1B 0.9% 3.8%

$1B< to $2B 0.5% 2.8%

$2B< to $10B 0.0% 1.7%

More than $10B 0.0% 0.1%

Total 1,266 4,979

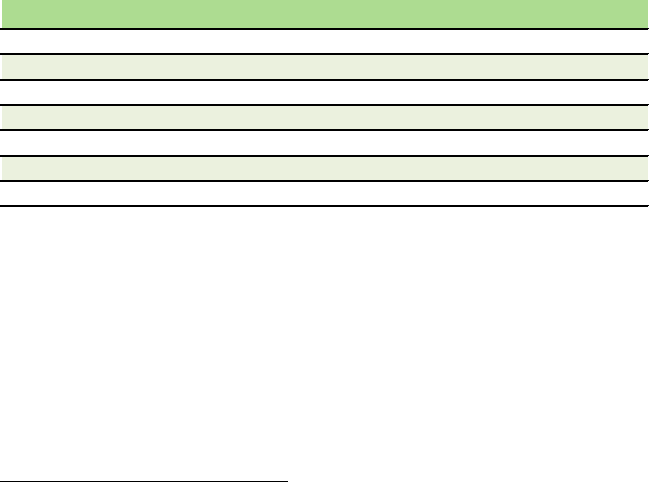

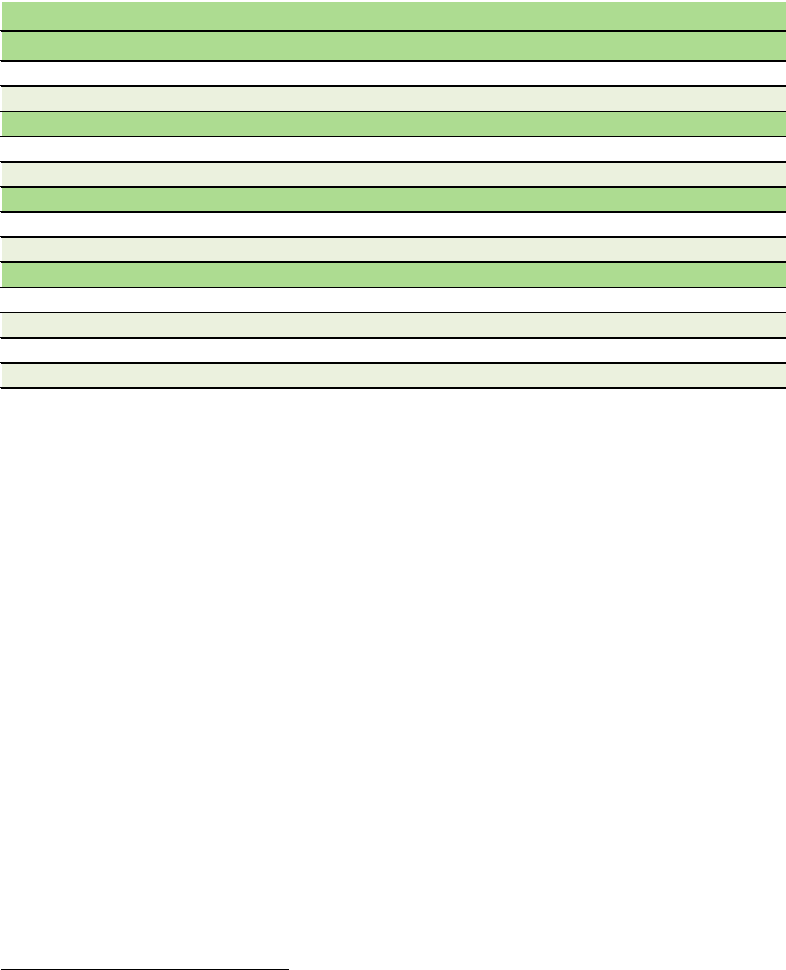

Table 2 compares the distribution by asset tier of banks in the core processor sample and in the

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Call Reports at the end of 2014

(restricting to banks with consumer deposit accounts to approximate for banks offering

checking account services). The two distributions line up with each other more closely than for

credit unions, though once again, larger institutions are underrepresented in the core processor

sample. Banks with over $2 billion in assets made up 7.3% of all banks with consumer deposit

accounts but only 3.9%

17

of the core processor sample. Overall, the core processor sample

captures 2,638 of the 4,550 banks offering checking account services, 58.0% of the total.

Comparing the asset tier distributions across institution types in the core processor sample, the

smallest asset tier ($100 million or less) contains just under a quarter of all of the banks in the

dataset while slightly more than four fifths of observed credit unions belong to this asset tier.

Institutions with assets over $550 million make up 20.1% of the bank sample but only 1.3% of

the credit union sample. Only 0.6% of the banks in the dataset had over $10 billion in assets.

The higher representation of banks in the core processor sample means that more than two-

thirds of the institutions in the sample are banks, even though there were more credit unions

offering consumer checking accounts in the U.S. than banks reporting consumer deposit

accounts in 2014.

17

Numbers reported in the text may not equal the sum of the individual components reported in the tables due to

rounding.

10

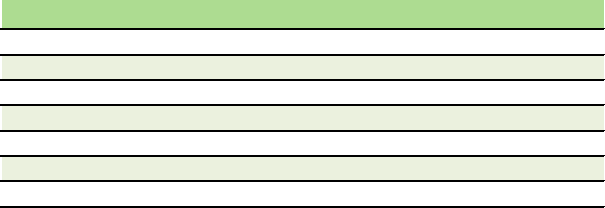

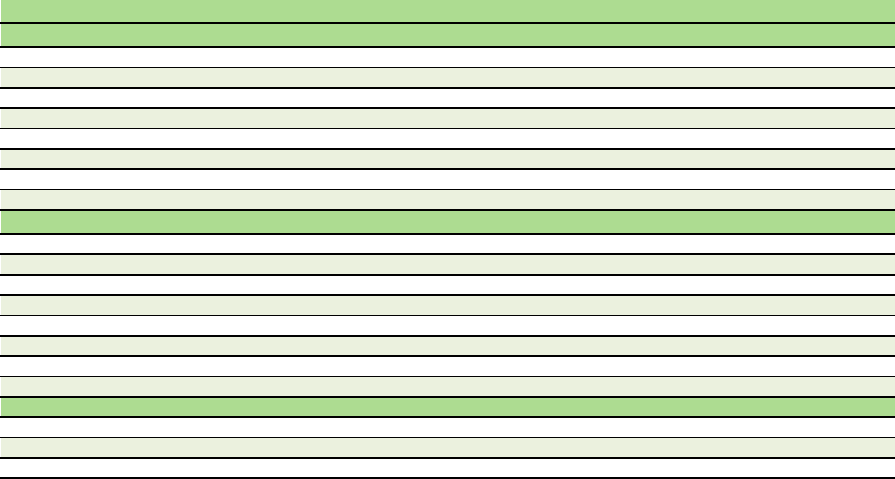

TABLE 2: DISTRIBUTION BY ASSET TIER OF BANKS IN THE CORE PROCESSOR SAMPLE AND OF

BANKS WITH CONSUMER DEPOSIT ACCOUNTS IN THE 2014 CALL REPORT DATA

Asse t ti e r

Core processor

sa m pl e

FFIEC Call Report

(banks with

consumer

deposits)

$100M or less 23.8% 23.3%

$100M< to $550M 56.1% 54.0%

$550M< to $1B 10.0% 9.7%

$1B< to $2B 6.1% 5.8%

$2B< to $10B 3.4% 5.2%

More than $10B 0.6% 2.1%

Total 2,638 4,550

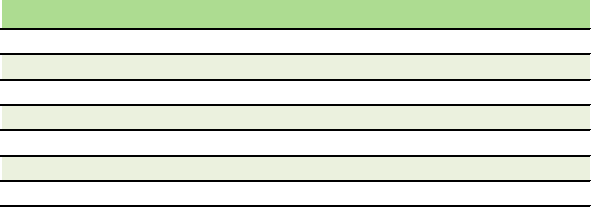

Table 3 shows the number of FIs and accounts in the core processor sample by institution type

and asset tier. Overall, the sample consists of about 30 million accounts at over 3,900

institutions. While most FIs in the dataset had $550 million or less in assets, a majority of

accounts were at institutions with assets over $550 million.

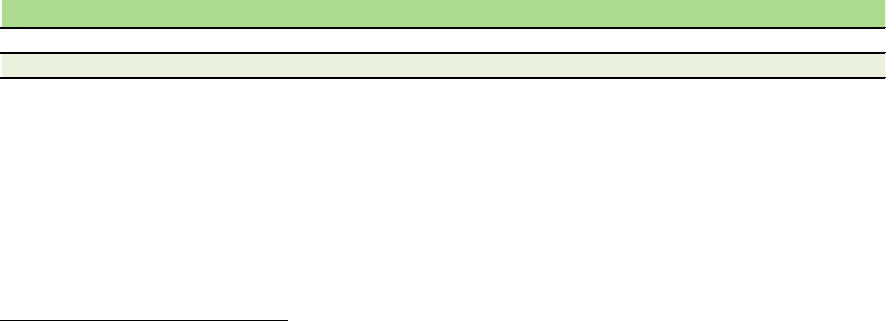

TABLE 3: NUMBER OF INSITUTIONS AND ACCOUNTS WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND ASSET TIER

CATEGORIES

Asse t tie r

Credit Union

FIs

Credit Union

accounts

Bank

FIs

Bank

accounts

$100M or less 1,018 2,598,884 627 1,788,796

$100M< to $550M 231 2,368,157 1,481 6,318,839

$550M< to $1B 11 323,340 264 3,155,608

$1B< to $2B 6 169,191 162 5,534,392

$2B< to $10B - - 89 5,599,730

More than $10B - - 15 2,150,455

Total 1,266 5,459,572 2,638 24,547,820

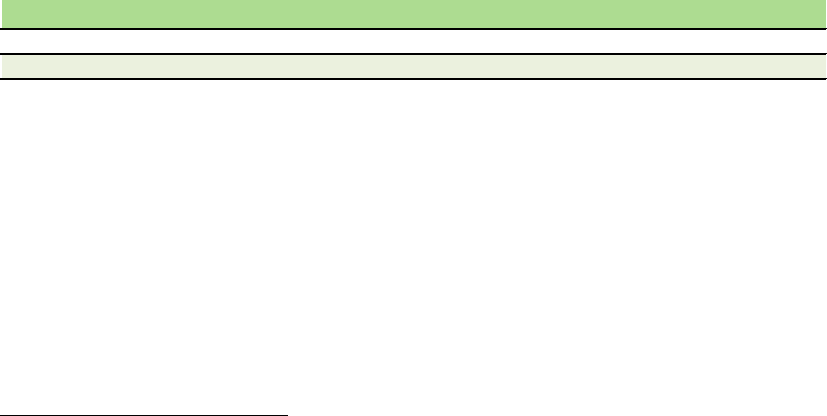

As can be seen in Table 3 above, there were only 11 credit unions in the $550 million to $1 billion

asset tier and six credit unions in the $1 billion to $2 billion asset tier in the dataset. There were

also only 15 banks with more than $10 billion in assets. These were also the categories for which

the share of FIs offering checking accounts that appear in the core processor sample was the

lowest. The core processor sample institutions were likely not representative of all credit unions

and banks that comprise these asset tiers (i.e., outside of this study). For example, the 15 banks

in the dataset with more than $10 billion in assets had 143,000 accounts on average. This figure

11

suggests that the banks in the dataset with $10 billion or more in assets were substantially

smaller, on average, than the nation’s very largest banks. Due to the small sample sizes and

shares represented, we do not report findings for these categories in subsequent sections of this

report, but they are included when calculating overall statistics by FI type.

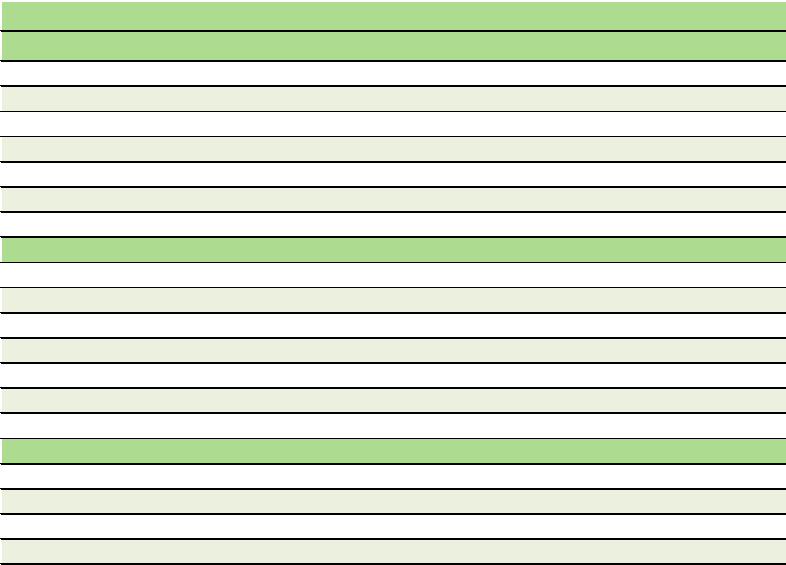

Table 4 shows the median number of consumer accounts at the end of the observation period at

the banks and credit unions in the dataset for each asset tier. Generally, credit unions in the

dataset had more consumer accounts than did banks in the dataset of the same asset tier.

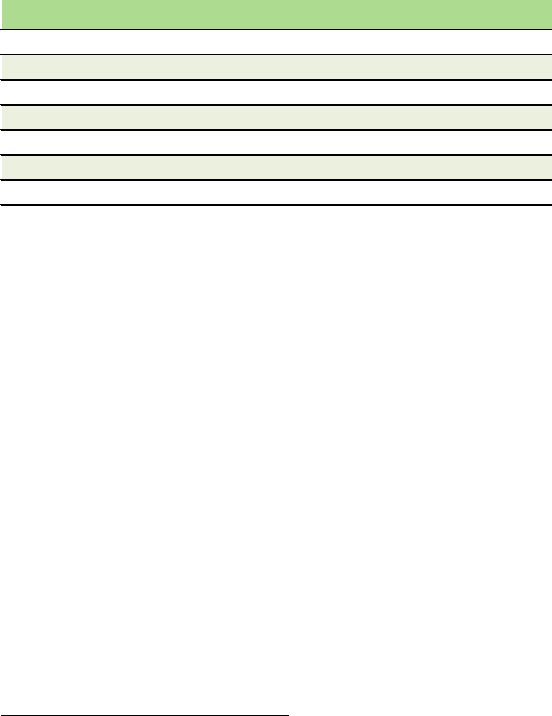

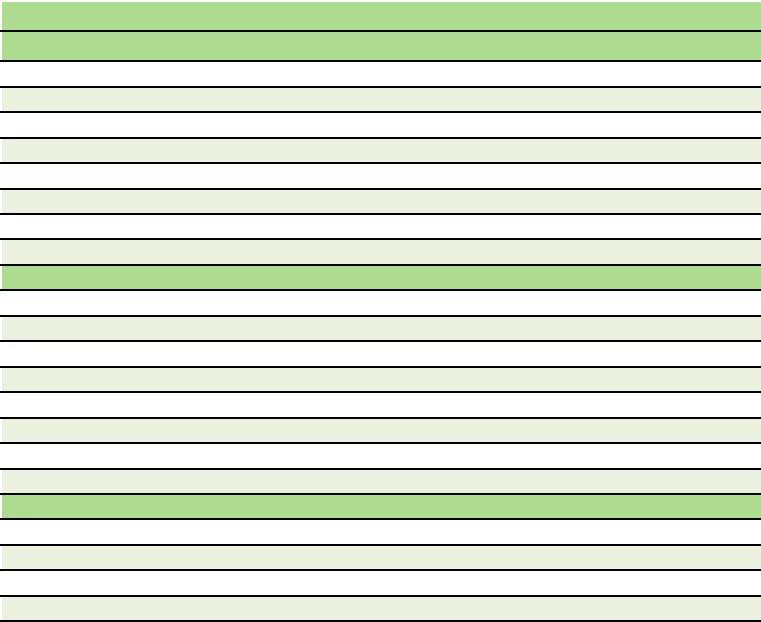

TABLE 4: MEDIAN NUMBER OF ACCOUNTS AMONG INSTITUTIONS WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE

AND ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

Asse t ti e r

Credit Union Bank

$100M or less

1,524 1,292

$100M< to $550M 8,015 3,330

$550M< to $1B * 9,651

$1B< to $2B * 19,707

$2B< to $10B 29,763

More than $10B *

Total 2,066 3,143

Note: * indicates small sample size.

There are several caveats to consider about the statistics reported using the core processor

sample. First, the sample of credit unions and banks is not necessarily representative of the

universe of credit unions and banks, even after controlling for asset tier. This is most obvious in

the case of the three categories with a small number of observations identified above, but it may

also be true for the other categories. The sample is non-random by construction since the choice

of core processor, the choice of whether to use the core processor on an online or in-house basis,

and the choice of settings that influence whether a core processor had enough information on an

FI to report data were all systematic and were influenced by an institution’s underlying

characteristics. For example, the demographic characteristics of a credit union’s membership

could vary with the population served by the credit union and correspondingly members may

have had varying demand for online and mobile services. This, in turn, could have impacted the

credit union’s decision to use a core processor and, if doing so, which core processor to employ.

However, as discussed in more detail in Appendix B, the credit unions in the core processor

sample were very similar in critical aspects (number of checking accounts, median balances in

checking accounts, share providing an overdraft program) to credit unions generally that used

12

online services from core processors or other vendors. In addition, credit unions using online

services were generally similar to credit unions using a core processor’s or other vendor’s

software in-house, although the latter were somewhat larger in terms of assets and membership.

These findings suggest that there is not a significant issue with the representativeness of the core

processor sample in terms of the observable characteristics examined.

Second, the Bureau neither requested nor obtained direct reports from individual FIs about

their overdraft policies, practices, and consumer outcomes. Rather, we have indirect

information on these items that we obtained from reports on software configurations at core

processors providing services to the FIs. For ease of exposition, we often talk about FI policies

and outcomes for consumers with checking accounts, but it should always be kept in mind that

these are inferred indirectly through the core processors.

Finally, the data provided by the core processors in response to our information request were

extensively reviewed to minimize problems related to inaccurate or inconsistent reporting of FI

configurations and outcomes. In some cases, a platform may have provided certain features for

client FIs that were not used by those institutions. For example, there are instances where it was

reported that a feature, such as linked savings accounts, was used by just a few accounts. As the

core processors explained, this often happened when the FI was testing functionality and

created test accounts, but the feature was then not actually provided to the FI’s customers.

When questions were identified as part of this review with respect to the accuracy of the data

(for example, where information provided in different fields seemed internally inconsistent or

when a particular value provided seemed implausible), Bureau staff consulted with the core

processors providing the data and made revisions where appropriate.

18

In addition, we have

dropped outliers when calculating certain statistics in circumstances where a small number of

18

For example, data received by the Bureau could have simple coding errors such as reporting $0 in overdraft

revenue when an institution did not have an overdraft program. In that circumstance, the overdraft revenue would

be recoded as N/A (no overdraft program) rather than $0, which could otherwise be used to calculate an inaccurate

average overdraft revenue per account. Some data may also be internally inconsistent. An example of internal

inconsistency would be a core processor reporting that a particular FI did not provide opt-in while also reporting a

positive number for accounts at that FI that are opted-in.

13

outliers would otherwise skew our results.

19

Findings that exclude outliers are noted in the

relevant sections of this publication.

19

For example, when reporting annual overdraft revenue per account for banks with opt-in, dropping 5% of outlying

observations (2.5% on each side of the distribution) results in observations with less than $3.47 or more than

$112.44 in annual overdraft revenue per account being dropped. The presence of such outliers is most prevalent

when we calculate statistics based on multiple data fields provided by the core processors, such as when we combine

total overdraft revenues and total number of accounts to calculate overdraft revenue per account. If the two fields

are not comparable (in accounts covered or in time coverage, for example), this could lead to erroneous values. We

minimize the influence of such erroneous values by trimming outliers.

14

3. Overdraft policies

Consumers with checking accounts sometimes initiate debit transactions in amounts that exceed

their account balances. When that occurs, FIs may respond in a number of different ways. Many

FIs provide consumers with the option to link a savings or credit account to the consumer’s

checking account. When a consumer has linked an account this way, if there are available funds

in the linked savings account or available credit in the credit account, the FI pulls funds from the

savings or credit account to cover the debit transaction, often charging a fee for doing so.

Alternatively, if the transaction cannot be covered via a linked account, an FI can choose to pay

an overdraft when the consumer has insufficient or unavailable funds in the checking account.

20

FIs often charge an overdraft fee for paying such a transaction, subject to regulatory constraints.

The overdraft fee is typically a fixed amount per transaction. If the institution does not pay the

transaction, the transaction is declined or returned, and depending on the type of the

transaction and institution policies, the institution may charge an NSF fee. Generally, FIs charge

NSF fees for returned checks or ACH transactions but not for declined ATM or debit card

transactions.

21

20

There is no uniform terminology for various overdraft programs, especially since many FIs have branded their

overdraft programs with unique names. Regulation E defines an “overdraft service” to mean “a service under which

a financial institution assesses a fee or charge on a consumer’s account held by the institution for paying a

transaction (including a check or other item) when the consumer has insufficient or unavailable funds in the

account.” 12 CFR 1005.17(a). Broadly, the term “overdraft” is understood to mean any program designed to allow

consumers to draw funds or credit from other sources to cover items that otherwise would not clear against a

designated checking account. The source could be the institution’s discretionary funds or the consumer’s own funds

in a linked savings account or available credit in a linked credit account. The primary focus of this report is the

overdraft program typically provided by FIs for a fixed, per-transaction fee, that draw on the institution’s

discretionary funds, which we often simply refer to as “overdraft.” We will discuss linked accounts in more detail in

Section 5.

21

Most debit transactions can be categorized as ATM, debit card, check, or ACH transactions. While there are other,

less frequent, transaction types (such as cash withdrawals from a teller, wire or online transfers, etc.), for the sake of

simplicity, we will refer to these four major types in our discussion when talking about debit transactions.

15

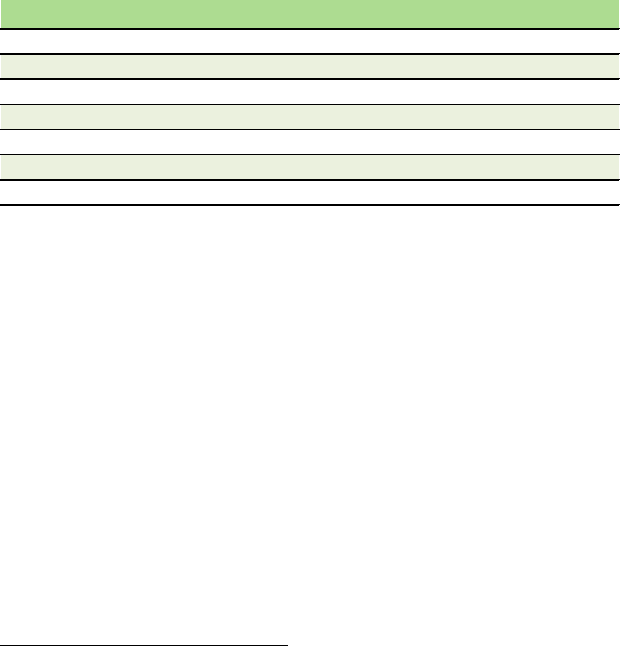

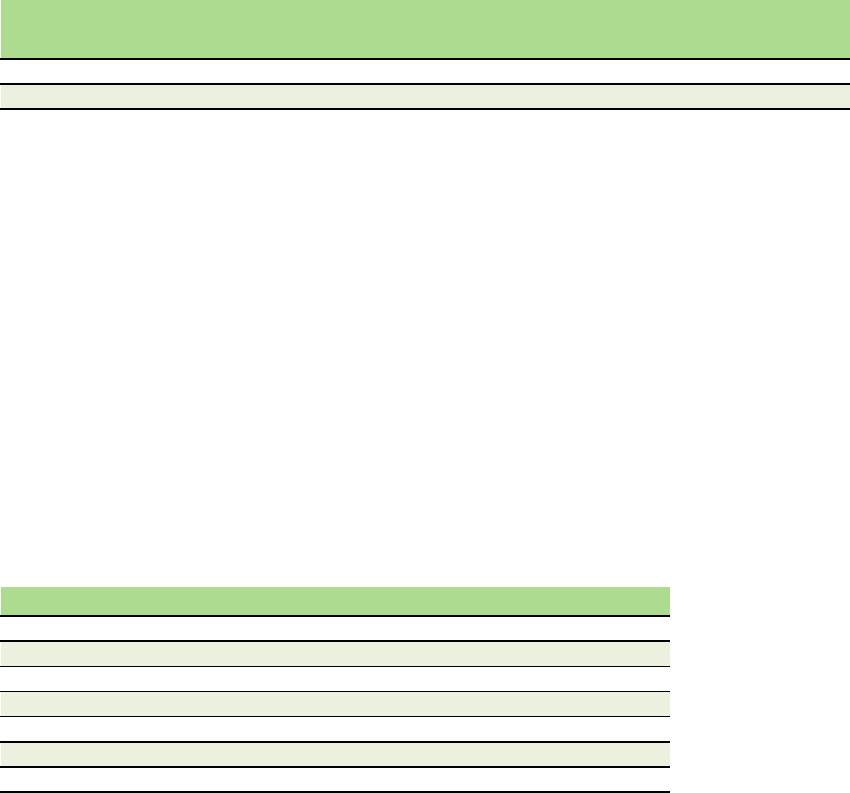

3.1 Overdraft programs

While overdraft is a common feature of checking accounts, it is not provided by all institutions.

In the core processor sample, 60.9% of credit unions and 92.9% of banks had an overdraft

program.

22

Table 5 shows the share of institutions that had an overdraft program by institution

type and asset tier. Overdraft programs appear less prevalent at the smallest institutions in the

dataset, especially at credit unions with assets of $100 million or less.

TABLE 5: SHARE OF INSTITUTIONS WITH AN OVERDRAFT PROGRAM WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE

AND ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

Among institutions in the sample that had an overdraft program, most made overdraft-related

decisions (discussed further in Section 3.4) using an automated system. At all observed

institutions using automated overdraft, some or all decisions were reviewed and could be

overturned manually. As shown in Table 6, only a handful of institutions were reported to

perform all overdraft decisioning manually, and these institutions were primarily small.

23

22

Data from the NCUA Call Report profiles at the end of 2014 show that, among all credit unions offering checking

account services, 61.1% had an overdraft program.

23

The information request relied upon the core processors to identify institutions with overdraft programs that only

use manual decisioning. However, certain FIs in the data that were reported to use manual decisioning were also

reported to provide overdraft on debit card transactions. Debit card network rules require that transaction

authorization/declination decisions are made in a near real-time manner, indicating that debit card transaction

authorizations, which then may result in an overdraft, are made in an automated fashion. These findings may

indicate that the core processors applied a broad definition of “manual decisioning” when providing responses.

Asset tier

Credit Union Bank

$100M or less 56.5% 89.1%

$100M< to $550M 79.2% 92.7%

$550M< to $1B * 96.6%

$1B< to $2B * 98.8%

$2B< to $10B 100.0%

More than $10B *

Total 60.9% 92.9%

Note: There are 1,266 credit unions and 2,638 banks in the sample,

of which 1,265 credit unions and 2,637 banks have information on

whether an overdraft program was provided.

* indicates small sample size.

16

TABLE 6: SHARE OF INSTITUTIONS USING EXCLUSIVELY MANUAL OVERDRAFT DECISIONING

AMONG THOSE WITH AN OVERDRAFT PROGRAM WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND ASSET TIER

CATEGORIES

Asse t ti e r

Credit Union Bank

$100M or less

5.4% 3.6%

$100M< to $550M 1.1% 0.8%

$550M< to $1B * 0.0%

$1B< to $2B * 0.0%

$2B< to $10B 0.0%

More than $10B *

Total 4.2% 1.3%

Note: There are 771 credit unions and 2,450 banks with an overdraft

program in the sample, of which 755 credit unions and 2,450 banks

have information on overdraft automation.

* indicates small sample size.

17

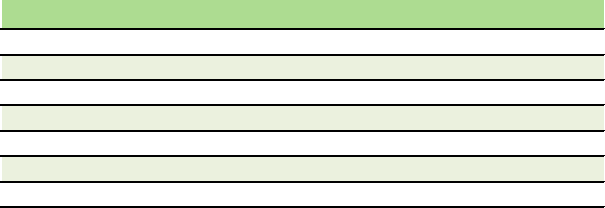

3.2 Opt-in

In 2009, the Federal Reserve Board amended Regulation E to regulate the practice of charging

overdraft fees on some transactions. Effective July 1, 2010,

24

institutions wishing to charge a fee

for overdrafts on ATM or one-time debit card transactions are required to obtain affirmative

consent; a consumer who does not provide affirmative consent is deemed to have not opted in.

While an institution may authorize ATM and one-time debit card transactions that result in a

negative balance on accounts that have not opted in, the institution may not assess fees for

paying these transactions.

25

Consequently, institutions typically decline ATM and one-time debit

card transactions on accounts not opted in that have an insufficient balance at the time of

authorization.

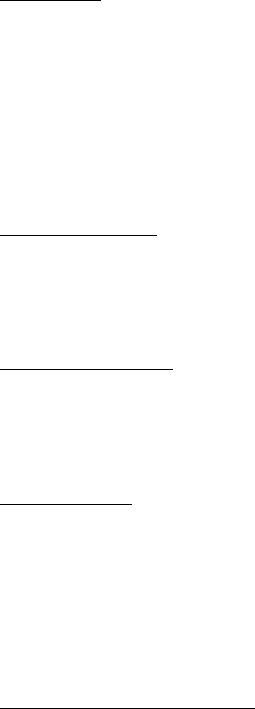

Table 7 displays the share of institutions with an overdraft program by institution type and asset

tier where consumers had the ability to opt in. Consumers had the ability to opt in at close to

three-quarters (73.2%) of observed credit unions and at three-fifths (60.7%) of observed banks

that had an overdraft program. Among both observed credit unions and banks, larger FIs were

more likely to have opt-in than those with smaller asset sizes. While there were institutions that

had opt-in on just ATM or one-time debit card transactions (but not both), 99.0% of observed

institutions’ opt-in regimes covered both ATM and one-time debit card transactions.

24

The amendment was effective August 15, 2010 for existing customers.

25

See 12 CFR 1005.17(b)(1).

18

TABLE 7: SHARE OF INSTITUTIONS WITH OPT-IN AMONG THOSE WITH AN OVERDRAFT

PROGRAM WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

As Table 8 demonstrates, the share of consumer accounts opted in (“the opt-in rate”) in the

dataset was generally higher at credit unions (29.9%) than at banks (20.2%) with opt-in.

26

However, the opt-in rate at the smallest banks (with assets of $100 million or less) in the dataset

was similar to the opt-in rate at credit unions. The overall bank opt-in rate in the dataset was

quite similar to that for the large study banks that provided the ability to opt in, which stood at

19.4% in 2011-2012.

27

26

Note that these are portfolio opt-in rates, i.e., they reflect the share of all accounts that were opted in at the end of

the observation period. The core processors did not report information on the opt-in rate of new accounts.

27

This latter number is derived from the monthly account-level data described in the 2014 Data Point but restricted

to institutions with opt-in.

Asset tier

Credit Union

Bank

$100M or less 68.5% 48.7%

$100M< to $550M 88.2% 59.9%

$550M< to $1B * 71.8%

$1B< to $2B * 80.0%

$2B< to $10B 83.0%

More than $10B *

Total 73.2% 60.7%

Note: There are 771 credit unions and 2,450 banks with an overdraft

program in the sample, of which 564 credit unions and 2,445 banks

have information on whether they provided opt-in.

* indicates small sample size.

19

TABLE 8: SHARE OF ACCOUNTS OPTED-IN AT INSTITUTIONS WITH OPT-IN WITHIN INSTITUTION

TYPE AND ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

Asse t Ti e r

Credit Union

Bank

$100M or less

30.3% 31.7%

$100M< to $550M 32.2% 19.3%

$550M< to $1B * 23.9%

$1B< to $2B * 21.7%

$2B< to $10B 14.4%

More than $10B *

Total 29.9% 20.2%

Note: There are 413 credit unions and 1,483 banks with opt-in in the

sample, of which 413 credit unions and 1,483 banks have information

on the share of accounts opted in.

* indicates small sample size.

The opt-in rate among credit unions with opt-in in the core processor sample varied

considerably, with a quarter of these credit unions having had opt-in rates of 13.2% or less and a

quarter having had opt-in rates of 38.4% or more. Similarly, a quarter of the banks with opt-in

in the core processor sample had opt-in rates of 7.8% or less and a quarter had opt-in rates of

28.8% or more.

20

3.3 Fee waiver policies

Many FIs have policies to waive overdraft and NSF fees under certain circumstances. One

example is a de minimis policy in which overdraft or NSF transactions are not assessed fees if

the transaction amount is below a certain size (a “per-transaction de minimis policy”) or if the

transaction would result in a negative balance that is less than a specified threshold (a “balance-

based de minimis policy”). Some institutions also have caps on the number of overdraft and NSF

fees that can be assessed in a business day. In addition, some institutions offer a forgiveness

period, a time period after the day an overdraft transaction posts during which the consumer

may deposit sufficient funds to return the account to a positive balance and avoid being charged

an overdraft fee.

28

De minimis policies

About one-fifth (20.1%) of credit unions in the core processor sample had some type of de

minimis policy, although it should be noted that less than 40% of credit unions with an

overdraft program had any information on such policies. As detailed further in Table 9,

observed credit unions more commonly employed a per-transaction de minimis policy rather

than a balance-based one. About two-thirds (67.3%) of banks in the dataset were reported to

have some type of de minimis policy. If offering any de minimis policy, banks in the dataset were

most likely to employ a combined per-transaction and balance-based de minimis policy.

TABLE 9: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY TYPE OF DE MINIMIS POLICY, IF ANY,

AMONG THOSE WITH AN OVERDRAFT PROGRAM

Institution type

Per transaction Balance-based Both None

Credit Union

17.7% 1.0% 1.3% 79.9%

Bank 5.5% 22.4% 39.4% 32.7%

Note: There are 771 credit unions and 2,450 banks with an overdraft program in the sample, of which

299 credit unions and 2,266 banks have information on de minimis policies.

28

FIs may also waive or refund fees occasionally on an ad hoc basis. This section does not capture such waivers or

refunds, only systematic policies.

21

The average per-transaction de minimis threshold was $9.45 among observed credit unions and

$8.80 among observed banks. The average balance-based de minimis threshold was $9.31

among observed banks.

29

Daily fee caps

Table 10 shows the share of observed FIs that imposed a daily cap on the overdraft and NSF fees

that an account could be charged. A higher share of observed banks appeared to have a daily fee

cap than observed credit unions, with the share increasing with asset size. Overall, 62.4% of

banks and 18.5% of credit unions in the dataset were reported to have a daily fee cap.

TABLE 10: SHARE OF INSTITUTIONS WITH A DAILY FEE CAP AMONG THOSE THAT CHARGED

OVERDRAFT AND/OR NSF FEES WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

While different configurations of fee caps are possible (for example, FIs may cap the combined

number of overdraft and NSF fees per day or cap each type of fee individually), for sake of

comparability, the cap amount is expressed as the maximum dollar amount of overdraft and

NSF fees that a consumer could be charged in one business day. Table 11 depicts the average fee

cap across observed institutions offering a cap, by institution type and asset tier. For banks, the

average daily fee cap was over $166, ranging from approximately $150 for banks in the smallest

asset tier to over $200 for the largest banks analyzed. The credit unions in the core processor

sample had an average daily fee cap of about $151. As we find in a subsequent section, the

29

As shown in Table 9, very few observed credit unions had a balance-based de minimis policy. Of those that did, no

dollar values were reported for the threshold.

Asset tier

Credit Union Bank

$100M or less 16.5% 50.4%

$100M< to $550M 21.2% 63.5%

$550M< to $1B * 68.4%

$1B< to $2B * 70.4%

$2B< to $10B 83.9%

More than $10B *

Total 18.5% 62.4%

Note: There are 1,217 credit unions and 2,630 banks that

charged overdraft and/or NSF fees in the sample, of which

745 credit unions and 2,267 banks have information on fee

caps.

* indicates small sample size.

22

average overdraft fee at these institutions was just under $30, implying that the number of fees

was capped at about five to six per day on average.

TABLE 11: FEE CAP AMOUNT AVERAGED ACROSS INSTITUTIONS WITH A CAP WITHIN

INSTITUTION TYPE AND ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

Forgiveness periods

Finally, forgiveness periods appeared more common at credit unions than at banks with the core

processors identifying 63.0% of credit unions as having provided these periods, compared to

1.2% of banks. Most commonly, a forgiveness period allowed a consumer to deposit funds to

cure a posted overdraft until a cutoff time that occured at or before the end of the next business

day (71.2% among credit unions and 85.1% among banks that were reported to have a

forgiveness period), though some institutions were reported to offer longer or other forgiveness

periods.

Asset tier

Credit Union Bank

$100M or less $163.65 $149.61

$100M< to $550M $119.12 $165.89

$550M< to $1B * $173.76

$1B< to $2B * $171.80

$2B< to $10B $201.01

More than $10B *

Total $151.18 $166.63

Note: There are 138 credit unions and 1,415 banks that had a

fee cap in the sample, of which 88 credit unions and 1,127

banks have information on the amount of the fee cap.

* indicates small sample size.

23

3.4 Decisioning policies

In general, FIs face two discrete decisions when faced with a transaction that would exceed an

account’s balance: first, whether to authorize/pay the transaction or decline/return the

transaction and second, whether to assess a fee with respect to the transaction. For ATM and

debit card transactions, these decisions can occur at separate points in time. The reason for this

is that an FI might not make a decision as to whether to charge an overdraft fee until the

transaction is posted to the consumer’s account, which can be one or more days after the

transaction was authorized.

30

For checks and ACH transactions, in contrast, the decisions of

whether to pay the transaction and charge a fee are generally made at the same time.

In this section we discuss the decisioning policies that the core processors reported for the FIs in

the sample. We also report results on whether and how institutions set an explicit amount by

which an account can be overdrawn (the “overdraft coverage limit”) that determined their

authorize/pay decision. We also discuss policies related to how quickly an FI made funds

deposited through electronic direct deposit available for consumers’ use as those policies could

affect whether a particular transaction was deemed to overdraw an account.

30

ATM and debit card transactions, once authorized, must be paid so that a decision to authorize is a commitment to

pay. Thus, these pre-authorized transactions are often described as “force-pay.” Checks and ACH transactions, in

contrast, generally are not authorized in advance and generally can be returned unpaid.

24

What is the difference between an available balance and a ledger balance?

Debits and credits to an account can take place before they settle (i.e., before funds are

disbursed between institutions) and post (i.e., the FI records the transaction on the

account). A consumer’s ledger balance is the net sum of all posted debit and credit

transactions against an account. The account’s available balance, in contrast, generally

keeps track of outstanding debits not yet settled and credits that have been posted but

are not yet cleared and thus fully available for withdrawal. Institutions’ information and

accounting systems use a set of rules to calculate the available balance by determining

when newly deposited items are deemed to increase the available funds in an account

and when a debit transaction is deemed to reduce the available funds in the account.

ATM and debit card transactions generally require an authorization at the time the

consumer initiates the debit. When a consumer’s FI provides an authorization, the FI

often reduces the consumer account’s available balance by the authorized amount.

Settlement and posting of ATM and debit card transactions can take place one or more

days after authorization, in part depending on the type of transaction (generally,

signature debit card transactions take longer to settle and post than ATM and PIN debit

card transactions). FIs are obligated to settle (pay the merchant’s FI) all ATM and debit

card transactions authorized up to the amount authorized. (For debit card transactions,

the authorization amount may differ from the actual amount of the transaction. For

example, at a restaurant the consumer typically authorizes the transaction for the pre-

tip amount while the actual amount of the transaction submitted for settlement

contains the tip.) Upon settlement, the transaction posts to the consumer’s account and

funds are deducted from the account’s ledger balance.

Most check and ACH transactions are not pre-authorized in the above manner.

Generally, an FI decides whether to pay or return these transactions when the

transaction is presented for posting. Rejected check and ACH transactions received are

returned, and FIs may assess an NSF fee in these instances. If the FI decides to pay a

check or ACH debit, the FI generally deducts the transaction amount from the account’s

available and ledger balance.

For a more detailed explanation, see the 2013 White Paper cited in footnote 3.

25

First, we requested information from the core processors on how their FIs determined whether

to authorize an electronic debit requiring authorization at the time of the transaction (ATM

withdrawals and debit card transactions) or decline it due to non-sufficient funds. As shown in

Table 12, we find that all banks and nearly all credit unions used available balance (reflecting the

funds immediately available for use) to decide whether to authorize these transaction types.

31

TABLE 12: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY BALANCE USED FOR

AUTHORIZATION/DECLINE DECISION FOR ATM AND DEBIT CARD TRANSACTIONS

Institution type

Available

balance

Ledger balance

Credit Union 99.6% 0.4%

Bank 100.0% 0.0%

Note: There are 1,266 credit unions and 2,638 banks in the sample, of

which 1,240 credit unions and 1,393 banks have information on the type of

balance used.

With regard to debits not already authorized (primarily checks and ACH transactions), FIs

usually determined whether to pay or return such transactions during posting, which occurs

after the consumer initiates the transaction. For such transactions, over 99% of credit unions in

the dataset were reported to use consumers’ available balance to determine whether to pay items

into overdraft or return them unpaid. In contrast, just under half of observed banks (45.2%)

relied on consumers’ available balance, as opposed to the ledger balance (balance of posted

transactions), to make this determination. These findings are summarized in Table 13.

31

In all instances in this section, we have combined the “available balance” (ledger balance adjusted for all

outstanding authorizations and holds on deposits) and the “adjusted available balance” (ledger balance adjusted for

certain outstanding authorizations and holds on deposits) responses under “available balance”.

26

TABLE 13: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY BALANCE USED FOR PAY/RETURN

DECISION ON DEBITS NOT ALREADY AUTHORIZED

Institution type

Available

balance

Ledger balance

Credit Union

99.5% 0.5%

Bank 45.2% 54.8%

Note: There are 1,266 credit unions and 2,638 banks in the sample, of

which 1,261 credit unions and 1,743 banks have information on the type of

balance used.

As can be seen in Table 14, nearly all credit unions (99.5%) in the dataset reportedly used

available balance to determine whether to charge an overdraft fee, while 44.4% of the banks in

the dataset did so. Among FIs for which the core processors reported an answer to both balance

questions, all but one was reported to use the same balance to decide whether to pay or return a

debit not already authorized, and — if the item was paid — whether to charge an overdraft fee.

TABLE 14: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY BALANCE USED FOR FEE DECISIONING

FIs that allow consumers to opt in per Regulation E must decide whether to charge overdraft

fees on ATM and one-time debit card transactions that result in an overdraft. As Table 15

demonstrates, 68.3% of the observed credit unions with opt-in decided whether to charge such

overdraft fees during posting after the transaction was presented for settlement. Among the

remainder of credit unions with opt-in, 6.8% reportedly determined whether to assess fees at

the time of authorization, while 24.9% reportedly did so at some other time (including during

posting at the end of the day on which the transaction had been authorized but before it was

presented for settlement). Less variability was present among the banks in the dataset with opt-

in, with 97.4% reportedly deciding whether to charge a fee during posting after a transaction

was presented for settlement, and the remainder doing so at the time of authorization.

Institution type

Available balance Ledger balance

Credit Union

99.5% 0.5%

Bank 44.4% 55.6%

Note: There are 1,217 credit unions and 2,630 banks that charged overdraft

and/or NSF fees in the sample, of which 1,201 credit unions and 1,483

banks have information on the type of balance used.

27

TABLE 15: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS WITH OPT-IN BY TIMING OF FEE CHARGING

DECISION FOR ATM AND DEBIT CARD TRANSACTIONS

As implied in Table 16, 91.5% of credit unions and 60.8% of banks in the dataset with an

automated overdraft program employed an overdraft coverage limit. FIs could either assign this

limit to each account individually (“individual overdraft limit”) or set a common limit for all

accounts (“common overdraft limit”). Within the dataset, the use of an overdraft limit overall

and the use of an individual overdraft limit specifically became more common as the FI became

larger.

TABLE 16: SHARE OF INSTITUTIONS BY TYPE OF OVERDRAFT COVERAGE LIMIT USED, IF ANY,

AMONG THOSE WITH AN AUTOMATED OVERDRAFT PROGRAM WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND

ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

Institution type/Asset tier

Individual

overdraft limit

Common

overdraft limit

OD limit used,

but type

unknown

No overdraft limit

use d

Credit Union - $100M or less

14.8% 29.8% 44.5% 10.9%

Credit Union - $100M< to $550M 24.1% 30.6% 44.1% 1.2%

Credit Union - $550M< to $1B * * * *

Credit Union - $1B< to $2B * * * *

Credit Union - Overall

17.0% 30.1%

44.5%

8.5%

Bank - $100M or less

11.4% 10.0% 18.7% 59.9%

Bank - $100M< to $550M 15.8% 15.3% 30.9% 38.0%

Bank - $550M< to $1B 23.8% 15.7% 34.3% 26.2%

Bank - $1B< to $2B 41.8% 16.4% 24.6% 17.2%

Bank - $2B< to $10B 46.8% 7.8% 28.6% 16.9%

Bank - More than $10B * * * *

Bank - Overall

18.9% 14.0% 27.9% 39.2%

Note: There are 739 credit unions and 2,419 banks with an automated overdraft program in the sample, of which

684 credit unions and 1,972 banks have information on overdraft limits.

* indicates small sample size.

Institution type

During posting,

after transaction

settled

At authorization Other

Credit Union 68.3% 6.8% 24.9%

Bank 97.4% 2.6% 0.0%

Note: There are 413 credit unions and 1,483 banks that provided opt-in in the sample, all of

which have information on the timing of the charge/no-charge decision.

28

While not strictly part of overdraft decisioning policies, an institution’s funds availability policy

determines how quickly a deposit is made available for the consumer’s use. Thus, funds

availability can affect whether or not an ensuing debit transaction overdraws an account. In this

regard, credit unions and banks appeared similar in the dataset as shown in Table 17, with about

a third of each generally making funds deposited through electronic direct deposit available

before the day of settlement and the remainder making funds available on the day of

settlement.

32

TABLE 17: SHARE OF INSTITUTIONS THAT MADE FUNDS DEPOSITED THROUGH ELECTRONIC

DIRECT DEPOSIT AVAILABLE BEFORE THE SETTLEMENT DATE WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND

ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

Asse t ti e r Credit Union

Bank

$100M or less 34.9% 30.1%

$100M< to $550M 48.9% 32.9%

$550M< to $1B * 28.0%

$1B< to $2B * 46.9%

$2B< to $10B 44.9%

More than $10B *

Overall 37.5% 33.2%

Note: There are 1,266 credit unions and 2,638 banks in the sample, all of

which have information on funds availability.

* indicates small sample size.

32

Specifically, our question asked about funds-availability practices regarding corporate to consumer (PPD) ACH

credits and was intended to capture an FI’s prevailing practice. Regulation CC ties funds availability for electronic

direct deposit to settlement, although it does not use that term. Specifically, 229.10(b)(1) states that an FI shall

make funds received by electronic deposit available for withdrawal “not later than the business day after the

banking day on which the bank received the electronic payment.” And, 229.10(b)(2), states that an FI is considered

to have received an electronic deposit when it has received (i) “Payment in actually and finally collected funds” [i.e.,

settlement]; and (ii) Information on the account and amount to be credited. In other words, Regulation CC requires

that funds from these deposits be made available on the day after the settlement date. In addition, in certain cases

the rules of NACHA, which govern the ACH network, require that funds from these deposits be available on the

settlement date.

Where the consumer does not use direct deposit, the law permits the FI to wait until the second business day after

the deposit to make the funds available. This information request did not include a question on how often FIs

imposed a waiting time, or the full waiting time, for such deposits.

29

3.5 Transaction posting order

FIs make many decisions regarding how transactions are processed. During the course of a

business day, an FI may have any number of transactions presented for settlement. FIs generally

receive checking account transactions in batch files. FIs may post these to the consumer’s

account as they are received in batches during the day (“intraday posting”), post these

transactions after the close of each business day (“nightly batch processing”), or use a

combination of these two options. FIs must also decide the order in which to post transactions,

such as whether to process credits before debits and whether to order transactions for posting

by type, size, timestamp, or a combination of these approaches. Although we did not ask the

core processors to provide comprehensive details, our information request asked several

questions related to how client FIs processed transactions.

First, Table 18 reports when FIs in the dataset processed transactions. Most banks in the dataset

(86.2%) used nightly batch processing, while most credit unions (82.4%) used a combination of

intraday and nightly batch processing. Among those observed institutions that used intraday

posting, nearly all (99.8% of credit unions and 100% of banks) assessed fees as those postings

occured throughout the day.

TABLE 18: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY TYPE OF TRANSACTION PROCESSING

SYSTEM USED

Institution type Nightly batch Intraday Combination

Credit Union 7.3% 10.4% 82.4%

Bank 86.2% 1.5% 12.3%

Note: There are 1,266 credit unions and 2,638 banks in the sample, all of which have

information on the type of transaction processing system used.

As noted previously, decisions must be made with respect to the order in which transactions are

posted to a consumer’s account. This ordering can affect the rate at which consumers incur

overdraft fees. Among FIs that were reported to engage in nightly batch processing (either

exclusively or in combination with some intraday processing), over two-thirds (67.6%) of credit

unions and 89.0% of banks processed all credits before any debits, as shown in Table 19.

33

Such

33

Intraday batches also must be ordered, but we did not collect information on the ordering of transactions within

batches that were posted intraday.

30

ordering lowers the likelihood of an account becoming overdrawn or a debit transaction being

returned due to non-sufficient funds. Of the remainder, nearly all processed only select debits

before credits according to their individual FI policy.

TABLE 19: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY THE ORDERING OF CREDITS AND DEBITS

AMONG THOSE USING SOME NIGHTLY BATCH PROCESSING

FIs using nightly batch processing may opt to post debits in the order in which they occurred

(chronological order) if those debits include a timestamp to make this possible (such as for

many teller and most ATM and debit card transactions). As Table 20 indicates, 64.7% of the

credit unions in the dataset employed timestamps to order debits chronologically, while 22.1%

of banks did so. The use of chronological ordering was somewhat more common among larger

institutions in the dataset.

TABLE 20: SHARE OF INSTITUTIONS THAT USED CHRONOLOGICAL ORDERING OF

TRANSACTIONS, IF POSSIBLE, AMONG THOSE THAT USED SOME NIGHTLY BATCH PROCESSING

WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

FIs are obligated to pay “force-pay” transactions, i.e., ATM and debit card transactions that the

FI has previously authorized, when they are presented for settlement. Of the banks in the

Institution type

Credits before

debits

Some debits

before credits

Debits before

credits

Credit Union 67.6% 32.4% 0.0%

Bank 89.0% 10.0% 1.0%

Note: There are 1,135 credit unions and 2,598 banks that used some nightly batch processing in

the sample, of which 1,115 credit unions and 2,527 banks have information on the ordering of

credits and debits.

Asset tier Credit Union Bank

$100M or less 63.6%

20.5%

$100M< to $550M 69.9% 20.3%

$550M< to $1B * 20.5%

$1B< to $2B * 33.1%

$2B< to $10B 46.1%

More than $10B

*

Overall 64.7%

22.1%

Note: There are 1,135 credit unions and 2,598 banks that used some

nightly batch processing in the sample, all of which have information on the

use of chronological ordering.

* indicates small sample size.

31

dataset that were reported to use nightly batch processing, 85.6% ordered transactions so that

force-pay debits were posted before those that were discretionary, i.e., not previously

authorized. The prevalence of this practice was reportedly lower among observed larger banks as

can be seen from Table 21. Credit unions in the dataset engaged in this practice less often than

observed banks, with 14.5% of observed credit unions having posted all force-pay transactions

ahead of other transactions which the credit union was not obligated to pay.

34

TABLE 21: SHARE OF INSTITUTIONS BY ORDERING OF FORCE-PAY DEBITS AMONG THOSE THAT

USED SOME NIGHTLY BATCH PROCESSING WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND ASSET TIER

CATEGORIES

When an FI uses nightly batch processing, it may group or “bucket” debits by transaction type

(e.g., debit card transactions vs. check), and then employ ordering rules within these groups

(“bucketed processing”). FIs may also commingle all debit transactions and apply rules affecting

the processing order to this single batch (“commingled processing”). Most of the FIs in the

dataset (80.8% of credit unions and 99.9% of banks) that used nightly batch processing were

reported to use bucketed processing as opposed to commingled processing, as can be seen from

34

Here and in some subsequent tables, credit unions are not broken out by asset tier due to small sample sizes in

some asset tiers and a lack of significant variation among the results across asset tiers with larger sample sizes.

Institution type/Asset tier

Force-pay debits

posted before

discretionary

de

bits

Some force-pay

debits posted

before some

d

iscretionary

debits

Credit Union - Overall 14.5% 85.6%

B

ank - $100M or less 93.4% 6.6%

Bank - $100M< to $550M 88.3% 11.6%

Bank - $550M< to $1B 80.6% 19.4%

Bank - $1B< to $2B 61.4% 38.6%

Bank - $2B< to $10B 57.1% 42.9%

Bank - More than $10B * *

Bank - Overall 85.6% 14.4%

Note: There are 1,135 credit unions and 2,598 banks that used some nightly batch processing in

the sample, of which 1,135 credit unions and 2,084 banks have information on the ordering of

force-pay debits.

*

indicates small sample size.

32

Table 22.

35

Of those credit unions that commingled all debit transactions, 27.0% ordered these

transactions from smallest to largest for posting (by the size, or absolute value, of transaction

amount) with the remainder not using size as an ordering criterion, including not using largest

to smallest ordering.

36

TABLE 22: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY TYPE OF NIGHTLY BATCH PROCESSING

USED AMONG THOSE THAT USED SOME SUCH PROCESSING

An FI that uses bucketed processing must determine which types of transactions (e.g., ATM,

debit card, check, ACH, etc.) to put in which bucket, in what order to post the buckets, and how

to order the transactions within each individual bucket.

To elicit information about these choices, we first asked the core processors to report how the

transactions in the bucket containing debit card transactions were ordered. Table 23 reports

these results for FIs that used bucketed nightly batch processing. Among credit unions reported

to use bucketed processing, 89.5% did not use size as an ordering criterion and another 9.7%

ordered transactions from smallest to largest. In contrast, 15.2% of banks reported to use

bucketed processing did not use size as an ordering criterion, with the remainder being roughly

evenly split between banks ordering transactions from smallest to largest (44.5%) and largest to

smallest (40.3%).

35

While 19.3% of the credit unions in the data commingled debit transaction for nightly batch processing, this

approach was concentrated among the smallest credit unions. 22.1% of credit unions with assets of $100 million or

less commingled debits, while just 3.4% of credit unions in the next asset tier (more than $100 million and up to

$550 million) did so.

36

Due to the very small share of banks that commingled debit transactions for nightly batch processing, we do not

report a similar statistic for these institutions.

Institution type Commingled

Bucketed

Credit Union 19.3%

80.8%

Bank

0.1% 99.9%

Note: There are 1,135 credit unions and 2,598 banks that used some

nightly batch processing in the sample, of which 1,060 credit unions and

2,460 banks have information on the type of nightly batch processing used.

33

TABLE 23: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY TYPE OF ORDERING USED WITHIN THE

DEBIT CARD BUCKET AMONG THOSE THAT USED BUCKETED PROCESSING

Next, we inquired about the buckets that did not include debit card transactions, with the

possible answers being: (1) transactions in at least one of these buckets were ordered from

largest to smallest; (2) transactions in at least one of these buckets were ordered by size, but

none are ordered from largest to smallest; or (3) none of these buckets were ordered by size. As

can be observed in Table 24, most banks reported to use bucketed processing employed some

type of ordering by the size of transaction within the non-debit card buckets, with 37.9%

ordering at least one bucket largest to smallest and an additional 58.8% ordering at least one

bucket by size in some other way. Credit unions reported to use bucketed processing were far

less likely to use size as an ordering criterion, with 66.8% not using size for ordering any of the

non-debit card buckets.

TABLE 24: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY TYPE OF ORDERING USED WITHIN THE

NON-DEBIT CARD BUCKETS AMONG THOSE THAT USED BUCKETED PROCESSING

Finally, we asked how the bucket containing debit card transactions was sequenced relative to

the buckets containing check and ACH transactions. Possible answers included: (1) the debit

card bucket was processed before any check or ACH buckets; (2) the bucket containing debit

card transactions also included check or ACH transactions; or (3) at least one bucket containing

checks and/or ACH transactions was processed before the bucket containing debit card

Institution type

Largest to

smallest

Smallest to

largest

No size ordering

Credit Union 0.8% 9.7% 89.5%

Bank 40.3% 44.5% 15.2%

Note: There are 856 credit unions and 2,458 banks that used bucketed nightly batch processing

in the sample, of which 836 credit unions and 2,386 banks have information on the ordering

inside the debit card bucket.

Institution type

Some largest to

smallest

Size ordering, but

no largest to

smallest

No size ordering

Credit Union 27.6% 5.6% 66.8%

Bank

37.9% 58.8% 3.3%

Note: There are 856 credit unions and 2,458 banks that used bucketed nightly batch processing

in the sample, of which 500 credit unions and 2,386 banks have information on the ordering

inside non-debit card buckets.

34

transactions. Most banks reported to use bucketed processing ordered the debit card bucket

before the check/ACH buckets (61.3%) or had the same bucket contain debit card and check or

ACH transactions (30.4%). Credit unions reported to use bucketed processing were less likely to

separate debit card and check or ACH transactions: 74.5% were reported to have the same

bucket contain debit card and check or ACH transactions as reported in Table 25.

TABLE 25: SHARE OF CREDIT UNIONS AND BANKS BY ORDERING OF THE DEBIT CARD BUCKET

AMONG THOSE THAT USED BUCKETED PROCESSING

Institution type

Debit-card bucket

processed before

check/ACH

buckets

Debit-card bucket

includes

check/ACH

transactions

Some check/ACH

buckets

processed before

debit-card bucket

Credit Union

1.4% 74.5% 24.1%

Bank

61.3% 30.4% 8.3%

Note: There are 856 credit unions and 2,458 banks that used bucketed nightly batch processing

in the sample, of which 572 credit unions and 1,521 banks have information on the ordering of

the debit-card bucket.

35

4. Overdraft and NSF revenue

To better understand the revenues that FIs in the dataset derived from the various fees related

to debit transactions that exceeded an account’s balance, we look at revenues and the

components of revenues, including fee amounts and the incidence with which these fees were

charged. For overdrafts, we report information both on fees and incidence, while for NSFs we

have just fee information. We also report on the share of FIs in the dataset that charged

additional fees when an account balance remains negative for a specified period of time

(“sustained negative balance fees”) and the revenue per account derived from these charges.

36

4.1 Overdraft fees, incidence, and revenue

Table 26 displays the per-item overdraft fee averaged across institutions with an overdraft

program within institution type and asset tier categories.

37

Across the sample, the average per-

item overdraft fee was $27.64 at credit unions while it was $29.55 at banks. The average

overdraft fee increased with asset size among observed banks: those with assets between $2

billion and $10 billion charged $32.22 on average, 15.9% higher than the $27.80 charged by

banks with assets of $100 million or less.

TABLE 26: PER-TRANSACTION OVERDRAFT FEE AVERAGED ACROSS INSTITUTIONS WITH AN

OVERDRAFT PROGRAM WITHIN INSTITUTION TYPE AND ASSET TIER CATEGORIES

Asse t ti e r Credit Union Bank

$100M or less $27.53 $27.80

$100M< to $550M $27.86 $29.52

$550M< to $1B * $31.25

$1B< to $2B * $31.51

$2B< to $10B $32.22

More than $10B *

Overall

$27.64 $29.55

FIs under $10B (Informa) $28.39 $31.89

Large banks (Pew) $34.05

Note: There are 771 credit unions and 2,450 banks with an

overdraft program in the sample, of which 751 credit unions and

2,432 banks have information on overdraft fees.

* indicates small sample size.

To provide context for these observations, we calculated the overdraft fee averaged across

comparable groups of institutions for the same time period from data provided by Informa, a

37

In our information request, we asked the core processors to indicate the amount of overdraft fee that client FIs

charged, if any. Some FIs varied the amount of the fee they charged, such as when fee amounts were tiered based on

the number of overdraft incidents in a business day. In cases of an institution charging a variety of overdraft fees, we

asked the core processors to provide the fee that was most frequently charged. While we allowed for reporting fees

that were not assessed on a per-transaction basis, no FI was reported to charge overdraft and NSF fees on a different

basis.

37

financial services market research company.

38

While the universe of institutions covered by the

data in this report and by Informa are different, the average overdraft fee statistics reported in