Long-Term

Community Recovery

Planning Process

A Self-Help Guide

December 2005

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .iii

FOREWORD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .v

I. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

PURPOSE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

WHAT IS LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

BENEFITS OF LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

USERS OF THE SELF HELP GUIDE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

II. BUILDING A LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PROGRAM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

STEP 1: ASSESSING THE NEED

Do we need long-term community recovery planning? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 2: SELECTING AN OVERALL LEADER and OUTLINING A LTCR PROGRAM

Where do we begin? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 3: SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT

Where can we get help? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 4: ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN

How do we keep the community informed and involved in the process? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 5: REACHING A CONSENSUS

How do we secure community buy-in to move forward? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 6: IDENTIFYING THE LTCR ISSUES

What are our opportunities? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 7: ARTICULATING A VISION AND SETTING GOALS

What will strengthen and revitalize our community? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

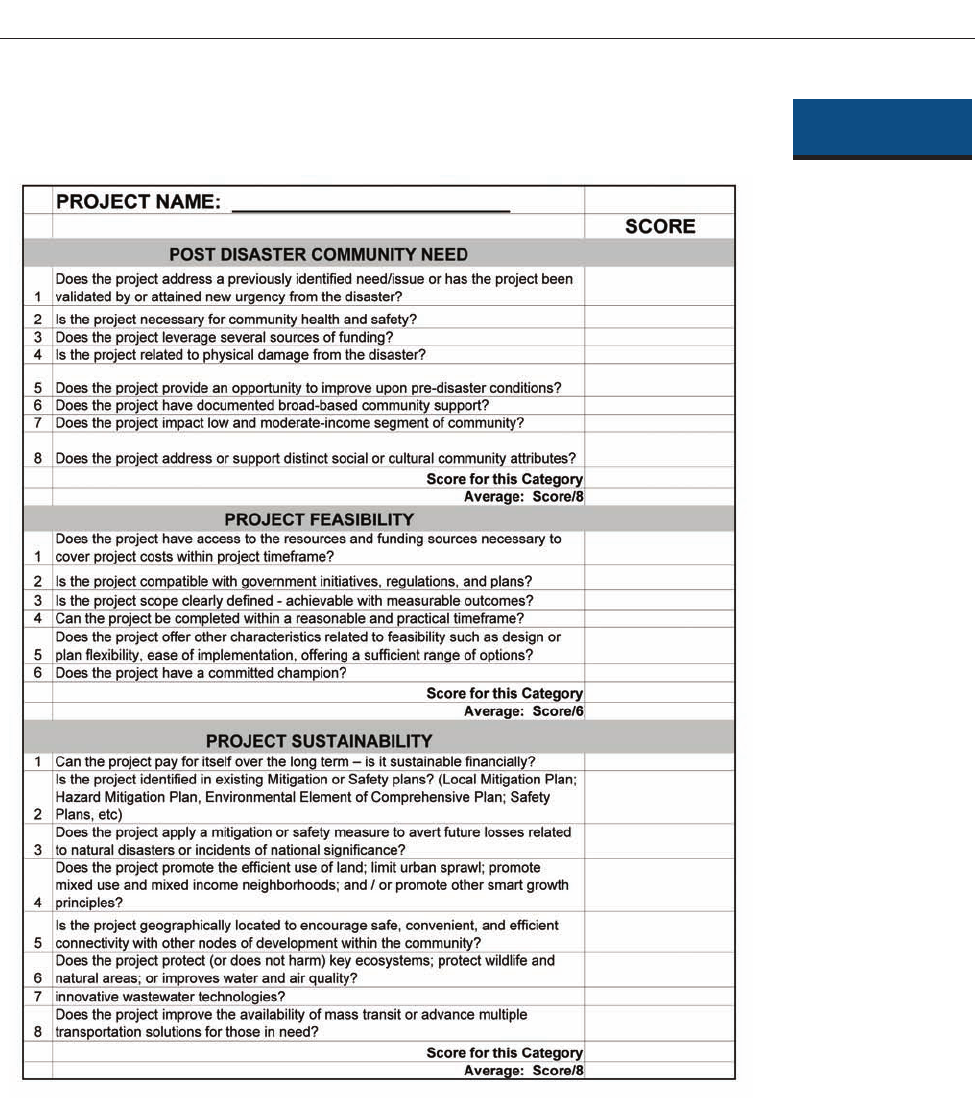

STEP 8: IDENTIFYING, EVALUATING AND PRIORITIZING THE LTCR PROJECTS

What makes a good project? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 9: DEVELOPING A RECOVERY PLAN

How do we put it all together? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 10: CHOOSING PROJECT CHAMPIONS

Who will provide leadership for each project? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 11: PREPARING A LTCR FUNDING STRATEGY

Where do we get the funding for these projects? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 12: IMPLEMENTING THE PLAN

How do we make it all happen? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STEP 13: UPDATING THE PLAN

When are we finished? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

III. WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .83

APPENDIX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .A - 1

LIST OF RESOURCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

LTCR PLANNING PROCESS CHECKLIST . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Table of

Contents

LTCR

TABLE OF CONTENTS

3

4

5

6

7

13

15

19

25

31

37

41

47

59

67

71

77

79

A - 3

A - 9

ii DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Table of

Contents

LTCR

LIST OF FIGURES

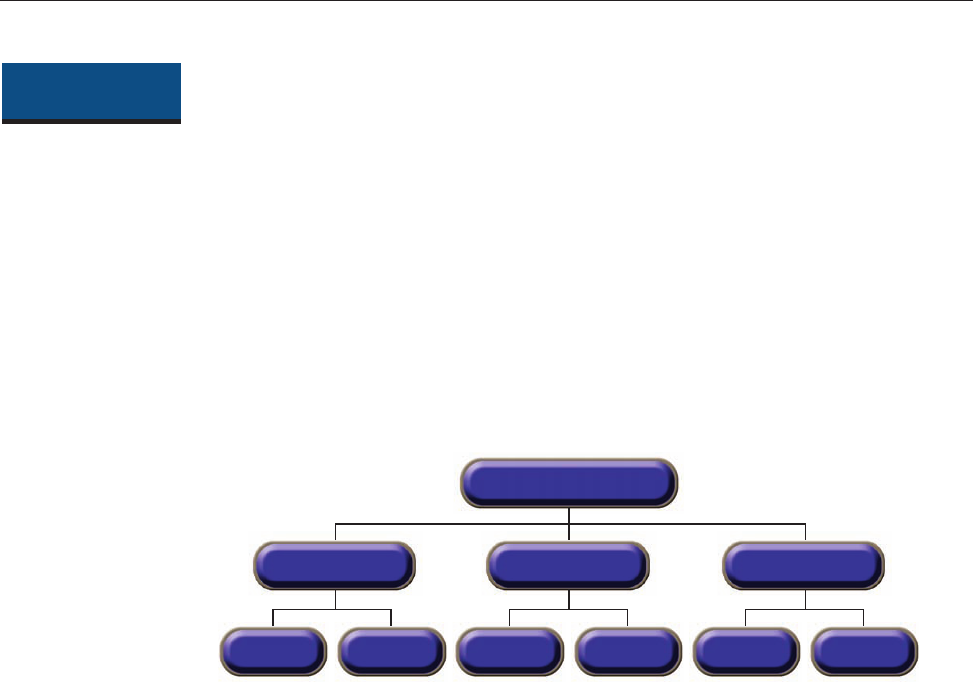

FIGURE 1 - CONCEPTUAL LTCR PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

FIGURE 2 - LTCR STEPS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

FIGURE 3 - LTCR STEPS AND OUTSIDE SUPPORT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

FIGURE 4 - NETWORK OF STAKEHOLDERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

FIGURE 5 - DECISION MAKING FRAMEWORK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

FIGURE 6 - EXAMPLE OF PROJECT GOAL STATEMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43

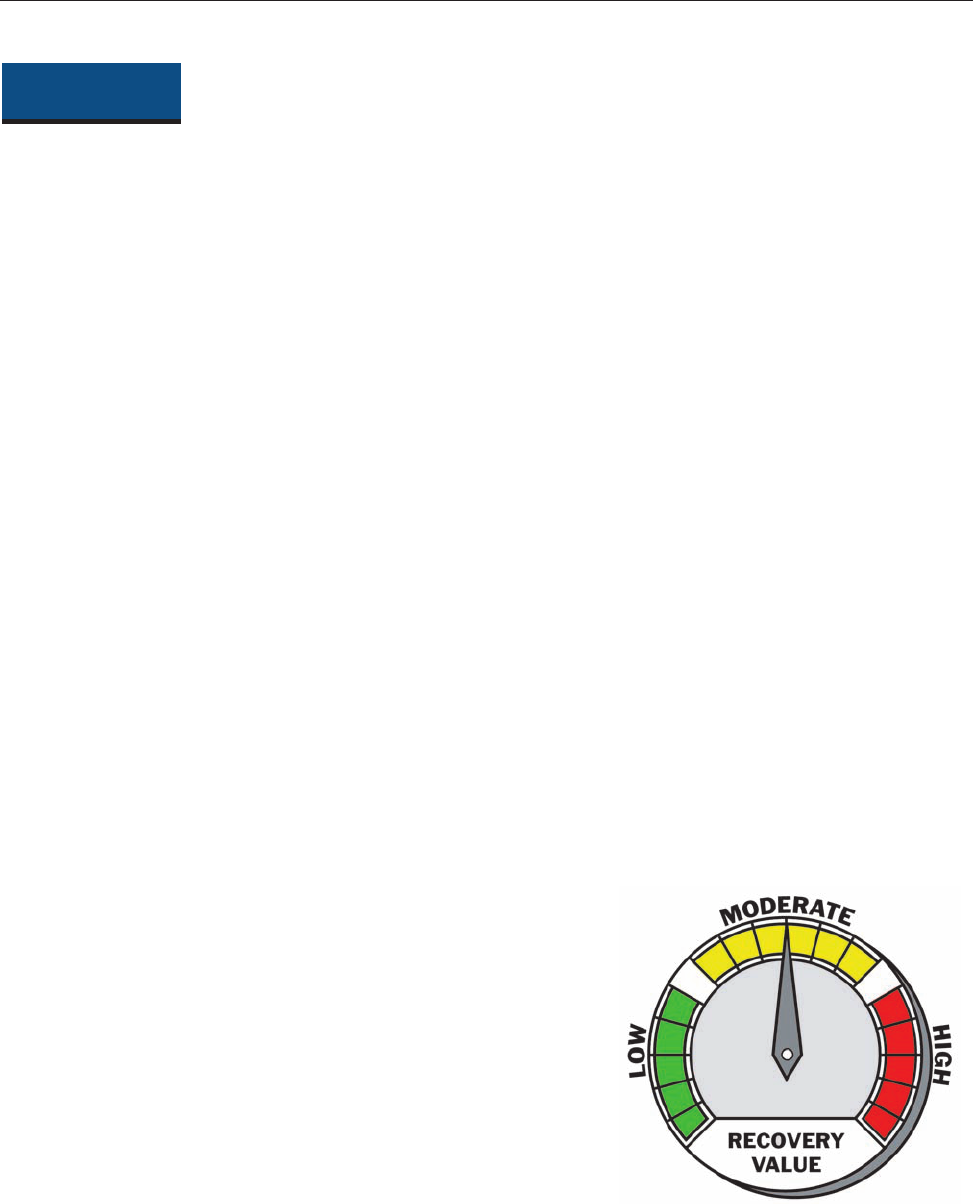

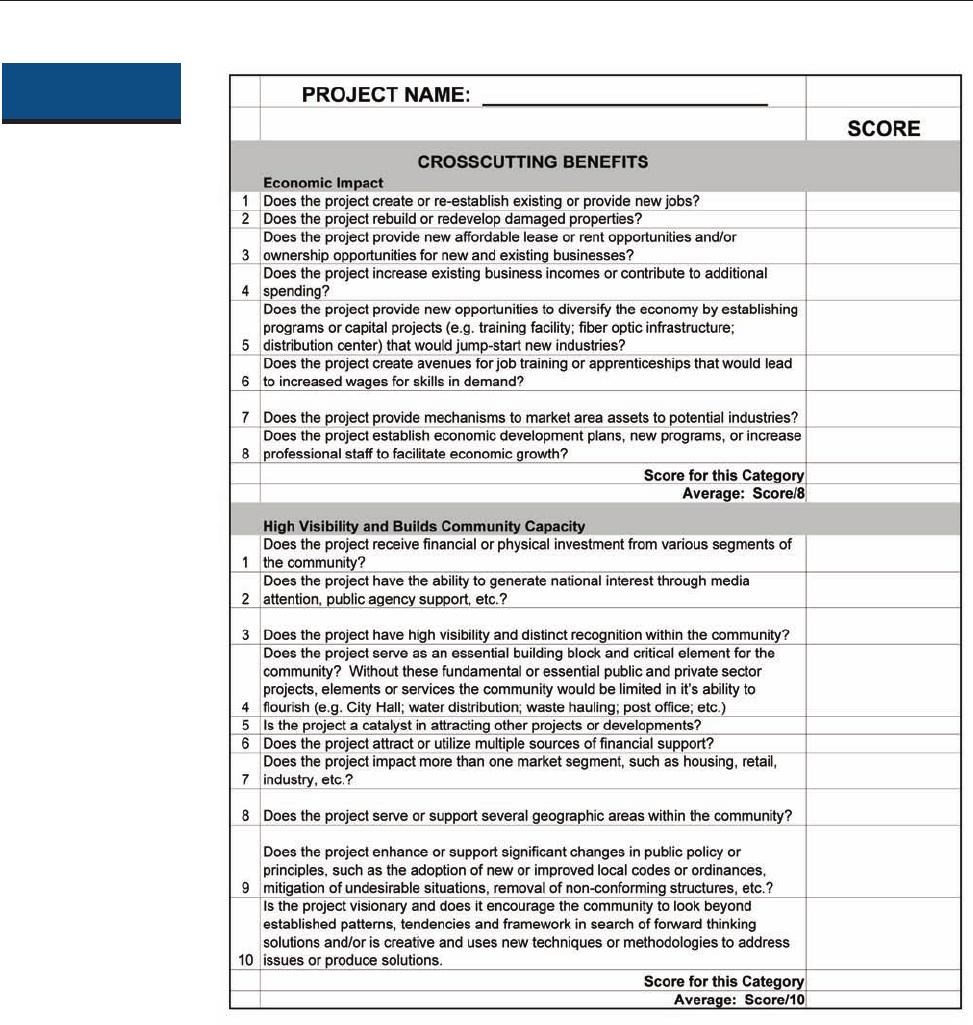

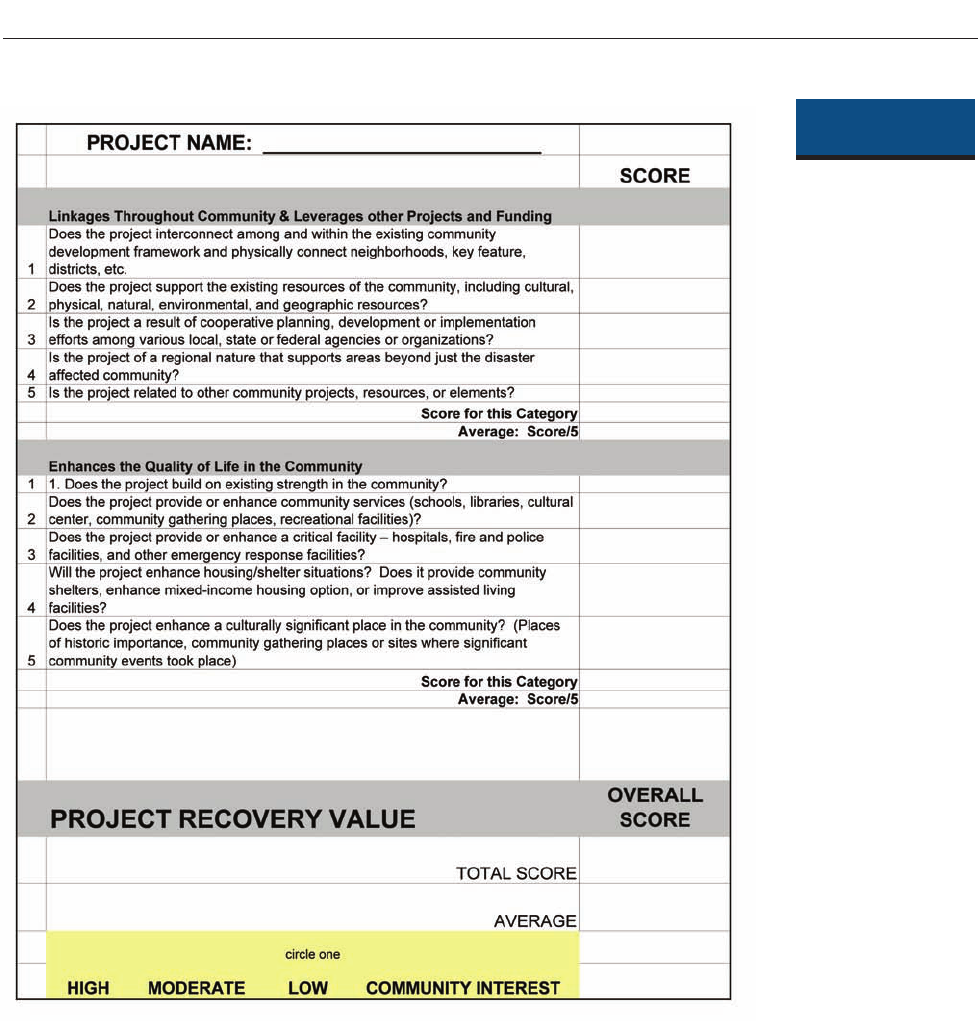

FIGURE 7 - RECOVERY VALUE DIAGRAM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .49

FIGURE 8 - COMMUNITY INTEREST DIAGRAM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51

FIGURE 9 - LTCR GENERALIZED TIME LINE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .61

FIGURE 10 - CONCEPTUAL FUNDING SOURCE DIAGRAM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .72

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 iii

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this document involved planners and architects who have participated in

local long-term community recovery initiatives over the past several years, U.S.

Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

headquarters personnel, ESF 14 partners and the Florida Long Term Recovery Office

(LTRO).

The long-term community recovery (LTCR) process is evolving. This Self-Help Guide

should be viewed as a preliminary document or interim draft for field-testing and is aimed

at continuing to pilot some of the concepts and methods that have been successful in the

past. Subsequent versions of the guide should incorporate lessons learned from current

and future LTCR efforts with a focus on tightening the organization, the level of detail, and

the depth of information in each of the steps. This guide will need to be assessed with

respect to its usefulness as currently written and will be revised as necessary, based on

feedback from its users.

LTCR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

iv DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

LTCR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 v

Foreword

Following certain disaster events, state, tribal, and/or local governments may wish to

undertake a long-term recovery program in which FEMA - using its long-term community

recovery assessment tool indicates that supplemental federal support is not required. The

FEMA Long-Term Community Recovery (LTCR) Self-Help Guide (guide) is intended to pro-

vide state, tribal and local governments with a framework for implementing their own

long-term community recovery planning process after a significant disaster event. It is

assumed that any state, tribal, or local government undertaking a LTCR Self-Help program

will have qualified staff to manage the planning process.

Every disaster is unique, but there are basic principles that can be applied to assist in

long-term recovery from the disaster.

This LTCR Self-Help Guide:

• Provides step-by-step guidance for implementing a LTCR planning program

based on the experience obtained and the lessons learned by teams of planners,

architects, and engineers over a period of several years and multiple experiences

in comprehensive long-term community recovery.

• Incorporates case studies for each of the steps in a LTCR program.

• Offers guidance and suggestions for involving the public in the recovery program

• Provides method for developing a LTCR plan that is a flexible and usable

blueprint for community recovery.

The Self-Help Guide is based on the experiences gained and lessons learned by communi-

ties in developing and implementing a long-term community recovery program. The

guide incorporates the knowledge gained by dozens of community planners as they

undertook the LTCR program and developed LTCR plans in disasters that varied in scope

from a tornado in a small town to the World Trade Center disaster.

There also may be a need for communities to modify the process set forth in this guide to

suit their particular needs. It is important that each community assess its own capability

to undertake LTCR planning. The guidance provided in this guide is based on a process

that has worked - but where outside technical assistance has been provided. If, after

reviewing the guide, local officials do not feel they have the capacity to lead and manage

this effort, consideration should be given to soliciting assistance from any of the resources

listed in STEP 3: SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT.

The primary function of the LTCR Self-Help Guide is to provide a planning template to

communities that have been struck by a disaster and/or the community has the resources

to undertake a LTCR program on its own. But this guide also may be useful for FEMA LTCR

technical assistance teams as they work with communities on long-term recovery and

may even be of assistance as a tool for teaching community preparedness in terms of put-

ting infrastructure in place for a LTCR program before a disaster occurs.

LTCR

FOREWORD

vi DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

FOREWORD

LTCR

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 1

Chapter I

INTRODUCTION TO

LONG-TERM

COMMUNITY

RECOVERY

LTCR

INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

2 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

LTCR

INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

I. INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

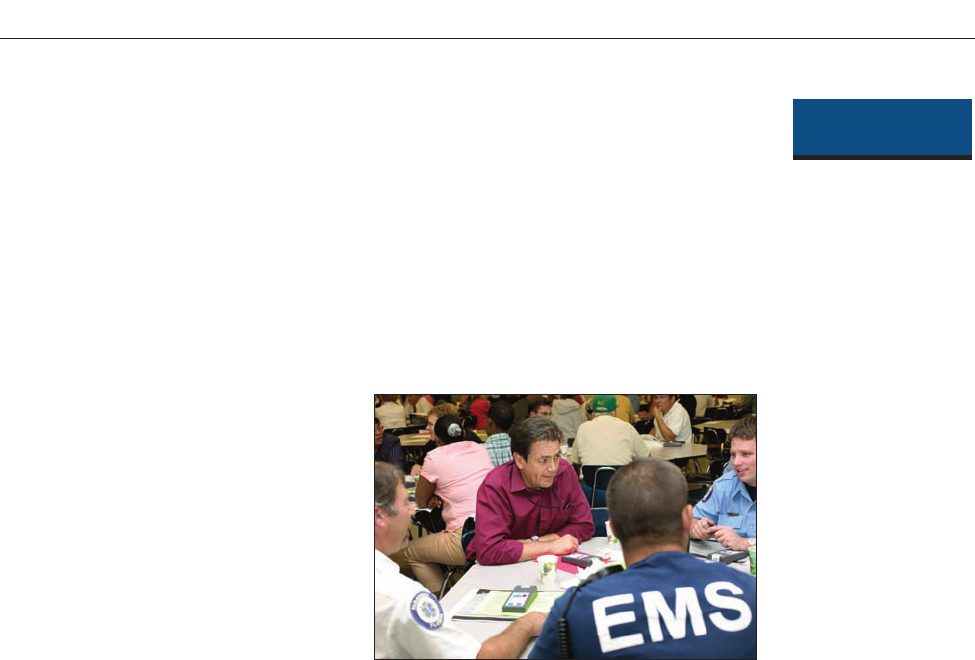

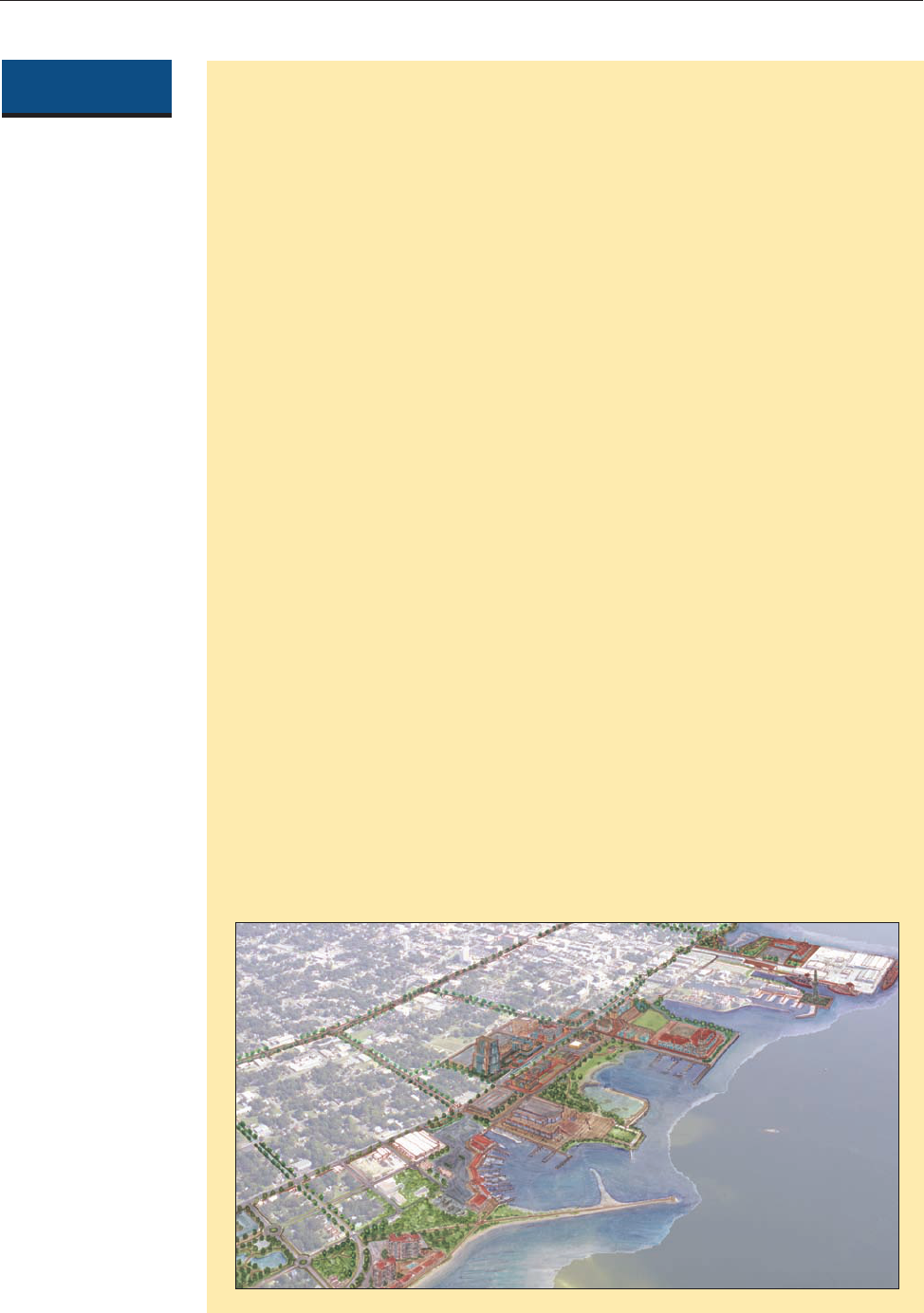

Stockton, Mo., a community with a population just under 2,000, was intent on recovering from

a May 4, 2003 tornado that completely destroyed its downtown, but community leaders were

unsure where to begin the recovery. According to Mayor Ralph Steele, some residents were

ready to build "a tin shack just to get back in business," but others wanted a more thoughtful

and comprehensive approach to recovery.

Supported by a FEMA long-term com-

munity recovery planning team, the

city initiated a three-month moratori-

um on building permits in the down-

town area. During that time, the city

undertook a LTCR planning program

with FEMA assistance and technical

advisors. The process involved local

officials, business owners, and resi-

dents and focused on making the com-

munity an even better place than it

was prior to the tornado. Downtown

business owners agreed to basic

design standards that focused on

brick facing for the buildings, consis-

tent setback standards, and an overall

redevelopment plan for the area.

Today, Stockton's downtown is alive

with activity from banks, a coffee and

gift shop, the county newspaper office,

various real estate and law offices, and

continued construction activity. Much

of the credit to the cooperative spirit

among the business owners, local gov-

ernment, and various state depart-

ments is the result of the LTCR plan-

ning process that stressed community

involvement and an outreach element

that solicited state and federal part-

ners in the recovery process.

Purpose

The purpose of this guide is to provide communities with a framework for long-term com-

munity recovery that has been used by FEMA and its technical advisors over the past sev-

eral years. This LTCR process has been successful in bringing communities together to

focus on their long-term recovery issues and needs and to develop projects and strategies

to address those needs. The recovery effort for these communities is still underway, but

the LTCR plan and the process employed to develop the plan has been a critical part of

their recovery effort.

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 3

THINK BIG!

The LTCR Planning Process is an opportuni-

ty to "think big." Don't limit yourself to

merely putting things back the way they

were prior to the disaster. Keep in mind

the quote attributed to Daniel Burnham,

the pioneer planner and architect who

supervised the construction of the

Columbia Exposition in 1893 and devel-

oped the Plan for Chicago in 1909.

“Make no little plans; they have no magic to

stir men's blood and probably will

themselves not be realized. Make big plans;

aim high in hope and work, remembering

that a noble, logical diagram once recorded

will not die.”

Chapter I

LTCR

Surveying the damage in Stockton, Mo.

4 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

The first step in long-term community recovery is the recognition by the community of

the need to organize and manage the recovery process as opposed to letting repairs and

rebuilding occur without a cohesive, planned approach. While FEMA is able to provide

assistance to the most critically impacted communities that do not have resources to

undertake a LTCR process, FEMA will not be able to provide that level of assistance to all

communities. This guide is designed for commu-

nities with the resources to undertake the LTCR

planning process themselves.

While this guide is based on processes that have

worked in other communities, each community

is unique and the damages sustained in a disas-

ter are going to be unique for each community.

Communities may need to modify the LTCR plan-

ning process set forth in this guide to suit their

particular needs.

What is Long-Term Community

Recovery?

Long-term community recovery - it is necessary

to focus on both the long-term aspect of the

phrase and the community recovery aspect.

Removing debris and restoring power are recov-

ery activities but are considered immediate or short-term recovery actions. These actions

are extremely important; however, they are not part of long-term community recovery.

"Long-term" refers to the need to re-establish a healthy, functioning community that will

sustain itself over time. Examples of long-term community recovery actions include:

• Providing permanent disaster-resistant housing units to replace those destroyed,

• Initiating a low-interest facade loan program for the portion of the downtown

area that sustained damage from the disaster (and thus encouraging other

improvements that revitalize downtown),

• Initiating a buy-out of flood-prone properties and designating them community

open space, and

• Widening a bridge or roadway that improves both residents' access to

employment areas and improves a hurricane evacuation route

The LTCR program should focus on development of a recovery plan that incorporates the

post-disaster community vision and identifies projects that are aimed at achieving that

vision. A community vision may have been identified prior to the disaster, but visions

INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

Chapter I

LTCR

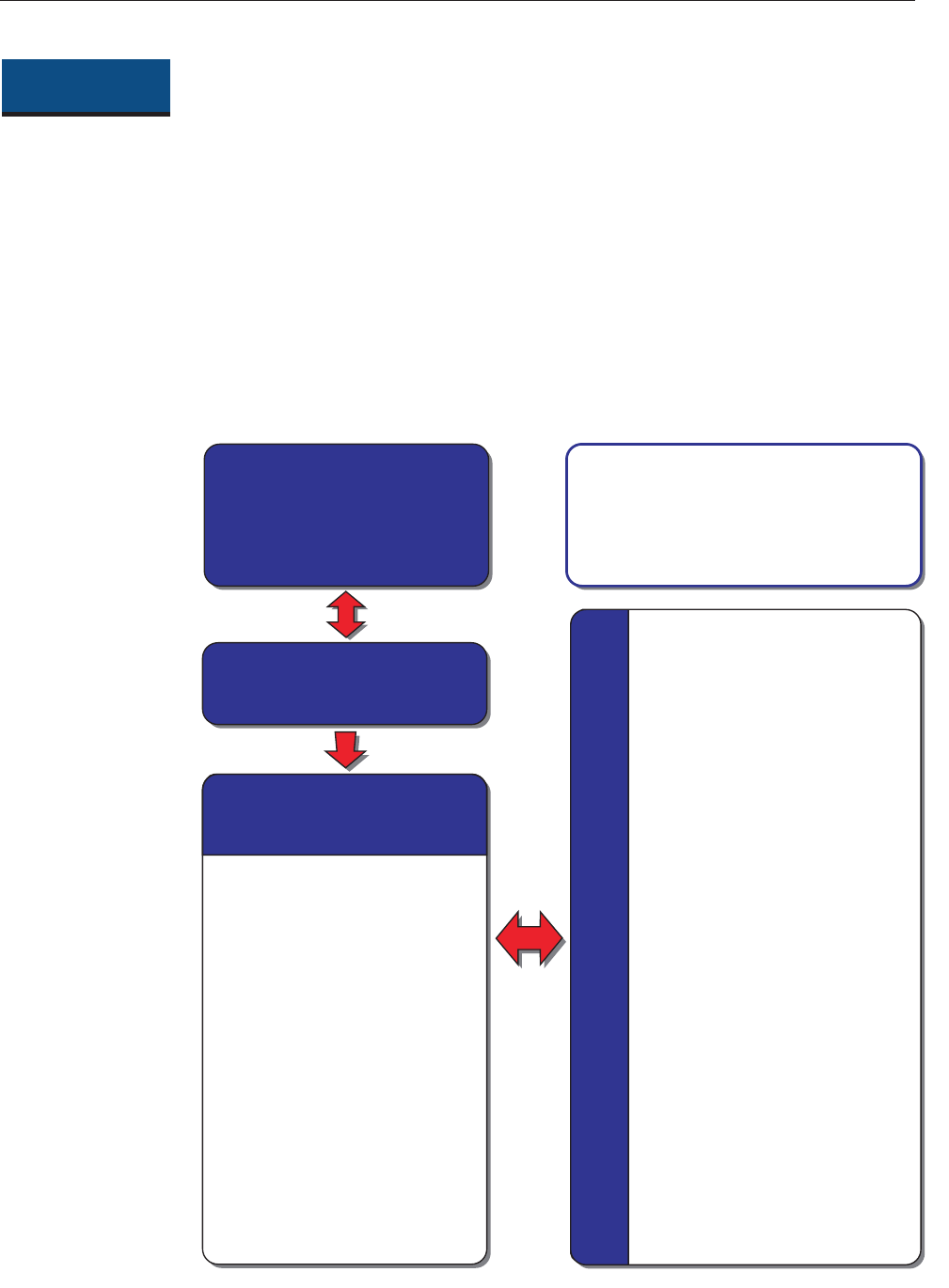

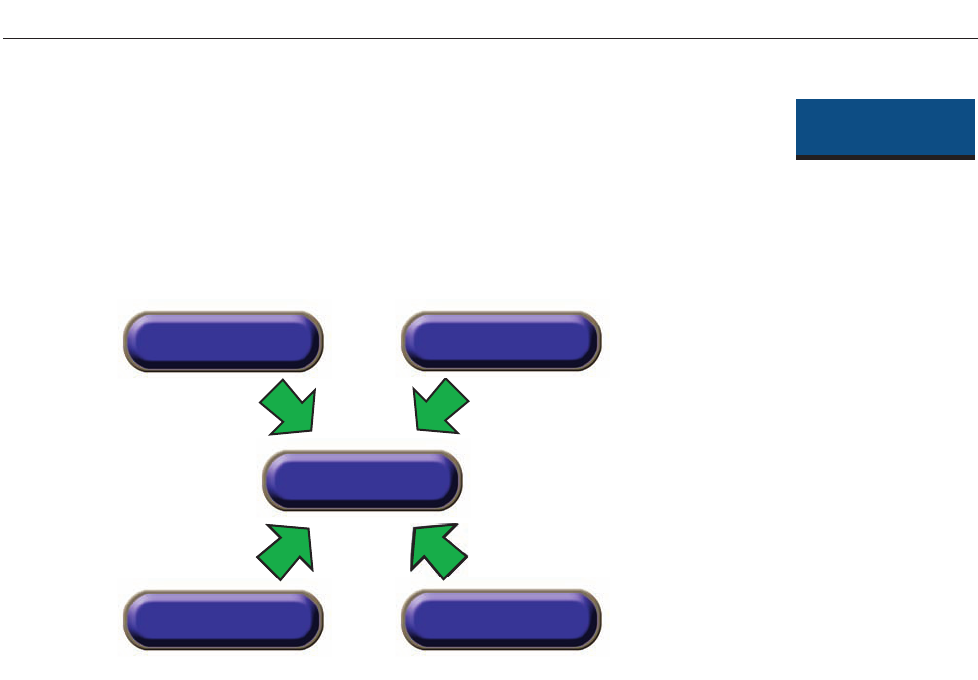

Disaster

Response and

Short-Term Recovery

LTCR

Planning

Community

Recovery

Figure 1

Conceptual LTCR Process

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 5

often change after a disaster. Disasters may even unveil new opportunities that were not

considered earlier. Long-term community recovery provides an opportunity to put a com-

munity back together in an improved way.

LTCR is the process of establishing a community-based, post-disaster vision and identifying

projects and project funding strategies best suited to achieve that vision, and employing a

mechanism to implement those projects. Each community's LTCR program is shaped by the

community itself, the damage sustained, the issues identified, and the community's post-

disaster vision for the future.

Based on past efforts using consultants, LTCR is typically a 6 to 12 week intensive planning

process setting the blueprint for community recovery after a disaster event. The length of

time for your planning process will depend on the resources you have available and the

amount of damage sustained.Your process will probably take longer unless the LTCR team

can devote full time to this effort. In most cases, the LTCR plan should be kept to a tight

time frame with tangible results to avoid public disillusionment with recovery efforts and

to take advantage of the sense of community that usually follows a disaster. Keep in mind

that this is not a typical strategic or master plan. This is a plan that should focus on recov-

ery from the disaster. Many actions taken in the weeks immediately following a disaster

will have long-term community impact. The LTCR program must be developed quickly in

order to provide direction and focus to community rebuilding efforts. Timing is an impor-

tant factor in LTCR.

Benefits of Long-Term Community Recovery

A LTCR plan benefits the affected community but also provides benefits to state and fed-

eral agencies assisting in recovery. The LTCR program consists of both a process and a

product - both are important. Key benefits of the LTCR program include the following:

• Organization - the program provides a consistent approach to LTCR and

promotes cooperation and coordination among federal, state, and local officials.

Chapter I

LTCR

INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

DISASTER RECOVERY

The ideal disaster recovery process is one where the community

proactively manages:

• Recovery and redevelopment decisions to balance competing interests so

constituents are treated equitably and long-term community benefits are

not sacrificed for short-term individual gains;

• Multiple financial resources to achieve broad-based community support

for holistic recovery activities;

• Reconstruction and redevelopment opportunities to enhance economic

and community vitality;

• Environmental and natural resource opportunities to enhance natural

functions and maximize community benefits; and

• Exposure to risk to a level that is less than what it was before the disaster.

Source: Holistic Disaster Recovery: Ideas for Building Local Sustainability after a

Natural Disaster.

6 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

• Holistic Community Recovery - attempts to incorporate all elements of the

community as part of the recovery process, encourages consideration of the

interrelationships of various sectors, such as commercial, environmental, etc., and

forces community, federal and state partners to look at long-term implications of

decisions.

• Focus - provides a clear path for recovery.

• Community Driven - involves and engages the community in the process.

• Hazard Mitigation Actions - provides an opportunity to incorporate hazard

mitigation concepts as part of the recovery effort to eliminate or decrease

exposure to damage in future

disasters.

• Community Healing - provides

opportunity for residents to join

together and function as a community

to vent their concerns, meet with one

another, and be involved in defining

and creating their future.

• Look Beyond Tomorrow - takes the

community and federal/state agencies

beyond response and into the

recovery process.

• Partnerships - fosters cooperation and coordination among federal, state, and

local agencies and organizations, both public and private.

• New Participants - creates an opportunity to bring in new participants and new

leaders from non-traditional sectors within the community.

• Empowerment - provides an opportunity for the community to take control of

its future and facilitate its recovery.

A product of the process (a LTCR plan) provides a road map to community recovery, but

the process employed to develop the plan can play a significant role in the community's

future through local partnerships and community consensus-building. The journey is as

important as the destination. The final products of the LTCR program are the completed

projects and the ultimate recovery of the community.

Basic Principles of Long-Term Community Recovery

LTCR planning is action-oriented and should support existing planning efforts in the com-

munity. The key principles of LTCR assure a focus on community recovery.

Key Principles

Long-term community recovery is:

• Community driven

• Based on public involvement

• Locally controlled

• Project-oriented

• Incorporates mitigation approaches and techniques

INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

Chapter I

LTCR

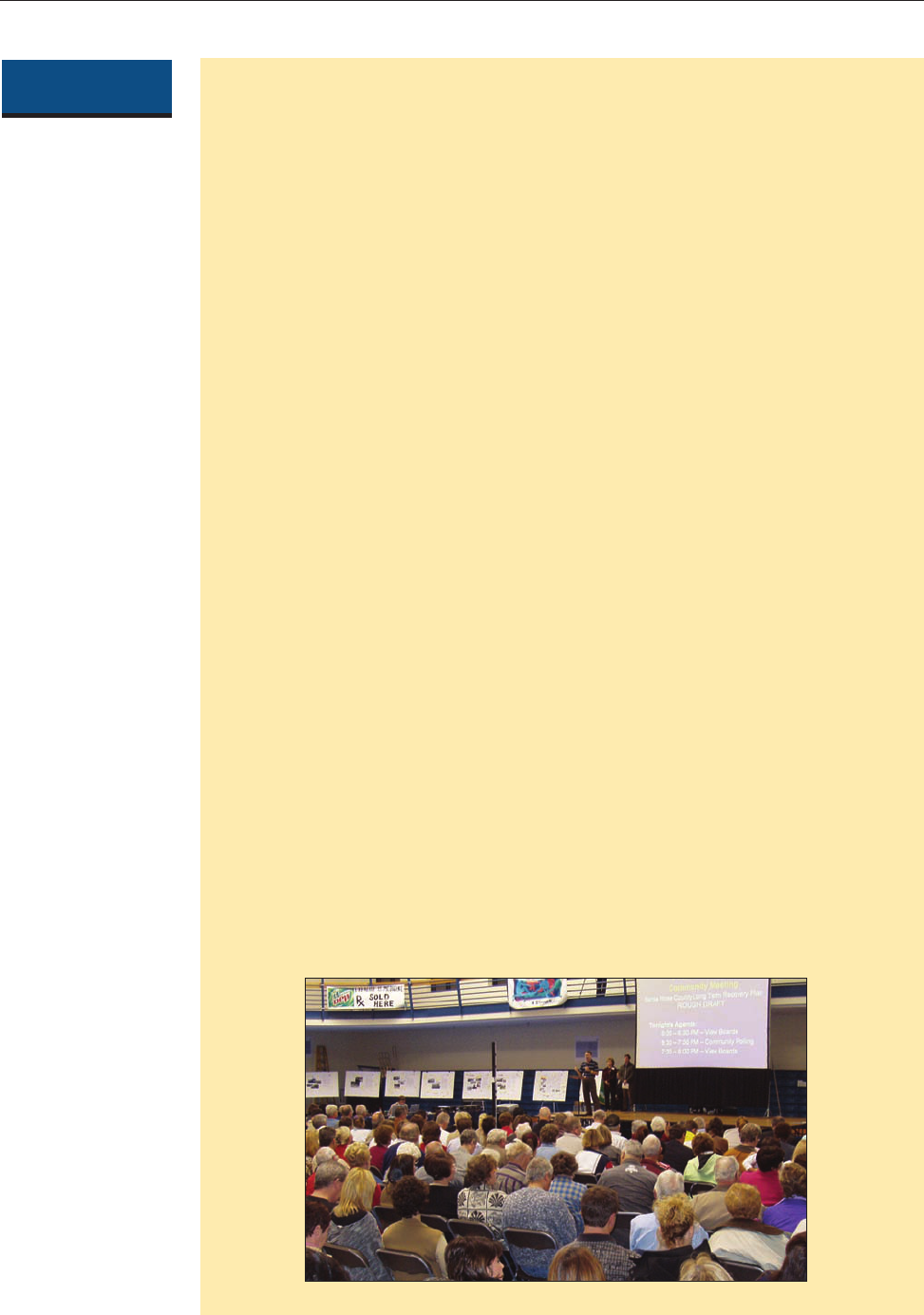

Community Meeting

INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 7

• A partnership among local agencies, jurisdictions, officials, and the state and

federal government

• Focused on projects that most contribute to community recovery from the

disaster

Effectiveness

LTCR can only be effective if the key principles are incorporated in the program. Critical to

the effectiveness of LTCR is the community involvement and consensus building process.

A LTCR plan and the projects contained in the plan will have a better chance to succeed if

there is strong community support. That support also will assist in soliciting funding for

key projects. Incorporating the principles and the steps outlined in subsequent sections

will assist in building consensus.

The partnership aspect of LTCR also is critical to its effectiveness since private sector, fed-

eral, and state agency involvement in the overall process will assist in identifying potential

funding for implementation. After all, the true effectiveness of a plan is measured by what

recommendations/projects are achieved and implemented.

The timing of achievements of the LTCR plan also plays an important psychological role in

the process and provides momentum in building consensus. Determining priorities in

achievements plays an important role in the community's perception of LTCR's success.

LTCR Planning and Comprehensive Planning

The LTCR planning process differs from the typical comprehensive planning process

because it is focused on plans and projects to address damages sustained from the disas-

ter and to aid in the community's recovery from the disaster. Existing plans, policies, and

studies must be reviewed and considered as part of the LTCR process. The LTCR plan is

strategic by nature and is action oriented. All aspects of the community may not be incor-

porated in the LTCR plan unless they were affected by the disaster.

In addition to the comprehensive plan, the LTCR planning process should take into

account other plans that have been prepared for the area or are underway.

• Local Mitigation Plans/Strategies - there are opportunities for collaboration of

the LTCR effort and Mitigation Planning activities. Mitigation techniques are

important considerations for projects in the LTCR plan.

• Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) - this EDA-sponsored

plan can provide support for LTCR strategies and may contain specific

recommendations for project development.

• Transportation Plans - prepared by the local Metropolitan Planning

Organizations, Regional Planning Commission, or State. The Transportation

Improvement Program (TIP) is especially important to review and coordinate.

Users of the Self-Help Guide

The intended users of the guide are communities that have the resources and capacities

to conduct long-term community recovery independently and would benefit from the

ability to implement an established and proven process rather than developing its own

process. Typically, damage to such a community would range from none or minimal for a

limited service government (has few full-time staff and usually no full-time administrator),

from none to moderate damage for a full-service government, and from none to possibly

one area of severe damage for a major metropolitan area government.

Chapter I

LTCR

8 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

It is important that communities have the resources and capacities to conduct long-term

community recovery. A limited service government may not have the resources within

the community but may be able to bring in a consultant, a Regional Planning Agency, or

volunteers to undertake a LTCR process if damages are minimal to moderate. Full service

governments and major metropolitan areas will typically have the resources to carry out a

LTCR process when the damages are not excessive.

Summary

This guide provides guidance for building a LTCR program, documents case studies, exam-

ples, and success stories, and offers guidance and suggestions for involving the communi-

ty in the recovery program. LTCR consists of a process and a product (a LTCR plan), both of

which are critical to the success of the program. Finally, the local, state, and federal part-

nerships required of the LTCR process will contribute to a more rapid and sustainable

community recovery.

This guide is just that - a guide. The material provides a template that has been used for

LTCR in the past. You may want to modify and/or refine the steps set forth in this guide to

suit your particular community and/or the resources at your disposal. The LTCR program

for your community is YOUR program.

INTRODUCTION TO LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY

Chapter I

LTCR

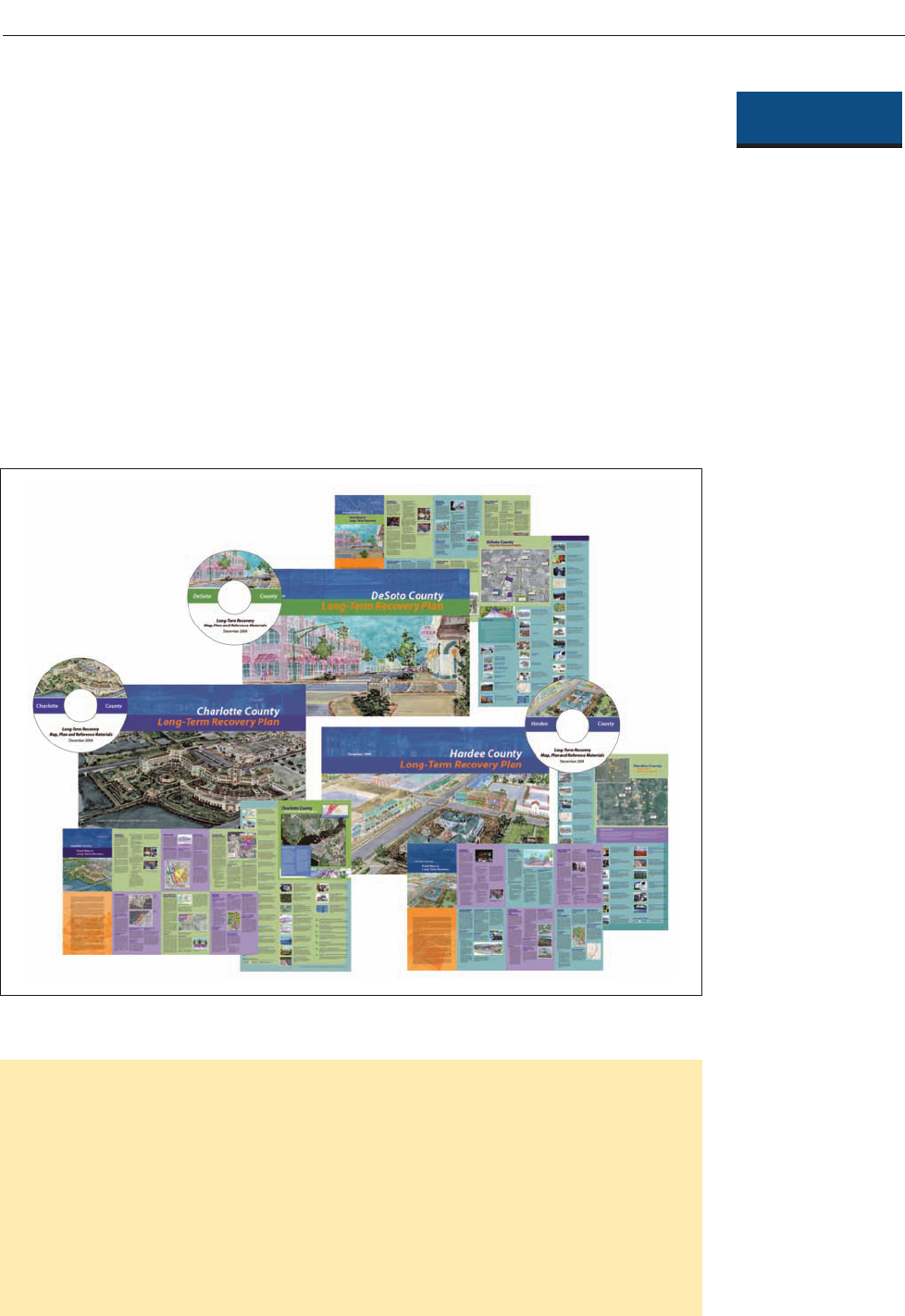

INFORMATION INCLUDED WITH SELF-HELP GUIDE

In addition to this guide other materials and information that might provide assis-

tance in carrying out the LTCR planning process in your community are available to

you. This includes:

• Results of the FEMA Needs Assessment that was conducted for your

community, (if undertaken)

• Compact Disc Containing:

• Electronic version of the LTCR Planning Process Self-Help Guide

• Recent LTCR plans and background materials

• Recovery Value (RV) Worksheet (Step 8)

OTHER RESOURCES

In addition to the materials provided with this guide, other documents/manuals

that may be of assistance include:

• Mitigation Planning 'How To' Guides, (FEMA Pubs. 386-1; 386-2; 386-3;

386-4; 386-6; and 386-7) http://www.fema.gov/fima/resources.shtm

• Technical Guidance Papers - P

lanning for Post-Disaster Recovery and

Reconstruction, Chapters 3, 4, and 5;

http://www.fema.gov/rrr/ltcr/plan_resource.shtm

•Holistic Disaster Recovery: Ideas for Building Local Sustainability after a

N

atural Disaster http://www.colorado.edu/hazards/holistic_recovery/

For a complete list of resources and information refer to the RESOURCES section in

the APPENDIX.

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 9

Chapter II

BUILDING A LONG-

TERM COMMUNITY

RECOVERY PROGRAM

LTCR

BUILDING A LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PROGRAM

10 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

BUILDING A LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PROGRAM

LTCR

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 11

Chapter II

LTCR

II. BUILDING A LONG-TERM COMMUNITY

RECOVERY PROGRAM

Typically, there are 13 separate steps that comprise the long-term community recovery

planning process. Some steps must be completed chronologically and others can be

done concurrently. The typical LTCR steps are:

Step 1: ASSESSING THE NEED - Do we need long-term community recovery planning?

Step 2: SELECTING AN OVERALL LEADER AND OUTLINING A LTCR PROGRAM -

Where do we begin?

Step 3: SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT - Where can we get help?

Step 4: ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN - How do we keep the

community informed and involved in the process?

Step 5: REACHING A CONSENSUS - How do we secure community buy-in to move

forward?

Step 6: IDENTIFYING THE LTCR ISSUES - What are our opportunities?

Step 7: ARTICULATING A VISION AND SETTING GOALS - What will strengthen and revi-

talize our community?

Step 8: IDENTIFYING, EVALUATING AND PRIORITIZING THE LTCR PROJECTS - What

makes a good project?

Step 9: DEVELOPING A RECOVERY PLAN - How do we put it all together?

Step 10: CHOOSING PROJECT CHAMPIONS - Who will provide leadership for

each project?

Step 11: PREPARING A LTCR FUNDING STRATEGY - Where do we get the funding for

these projects?

Step 12: IMPLEMENTING THE PLAN - How do we make it all happen?

Step 13: UPDATING THE PLAN - When are we finished?

Each of these steps is important in the overall process. The following sections detail each

step.

BUILDING A LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PROGRAM

12 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

LTCR

BUILDING A LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PROGRAM

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 13

LTCR

STEP 1:

ASSESSING THE NEED

Do we need long-term community recovery planning?

What are the Community Needs?

FEMA has developed an " Assessment

Tool" used to assess the long-term impact

of damages sustained by a community

and the resources and capacity of the

community to recover from the disaster.

This assessment focuses on damages and

resources in three general areas:

• Housing Sector

• Infrastructure/Environment Sector

• Economy Sector

The level of federal involvement in the

LTCR process is based on the findings of

the assessment as well as input from

other state and local sources that can

identify specific community needs. Based

on experience in other disasters, these are

the three general categories of need in a

community during the disaster recovery

process.

Focusing on the Specific Needs

of Your Community

The LTCR program should focus on the

specific long-term disaster-related needs

of your community. These disaster-relat-

ed needs typically fall into the three cate-

gories identified above, but other needs

may emerge that are unique to your

community. You can use the LTCR

process, or adapt it as necessary to

address these additional issues. Use the

results of the FEMA assessment to pro-

vide focus to the LTCR process. If the

Housing Sector is identified as represent-

ing a significant community need and

other sectors do not necessarily show a

need, the LTCR process should focus pri-

marily on the housing needs.

Identification of specific issues and proj-

ects related to these needs are addressed

in subsequent steps in the LTCR program.

Chapter II

Step 1

Assessing the Need

ASSESSING THE NEED • STEP 1

CONSIDER CONDUCTING

A SWOT ANALYSIS

• What are the community's

STRENGTHS?

• What are the community's

WEAKNESSES?

• What are our

OPPORTUNITIES as a result

of the disaster?

• What are the THREATS?

Housing

Infrastructure

Economy

14 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Chapter II

Step 1

Assessing the Need

LTCR

STEP 1 • ASSESSING THE NEED

WHAT ARE YOUR COMMUNITY'S NEEDS AS A RESULT OF THE

DISASTER?

• What extent/type of damages did we sustain and to what areas?

• What are the potential long-term impacts of these damages?

• What do we need if we don't undertake LTCR?

• What are the housing needs in the community? Quantity? Quality/Type?

Location? Obstacles?

• What are the community infrastructure needs or environmental issues that

need to be addressed? Are these existing? Growth plans?

• What are the community's economic needs as a result of the disaster? New

economic opportunities? Bolstering current opportunities?

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 15

Chapter II

Step 2

LTCR

STEP 2:

SELECTING AN OVERALL LEADER AND

OUTLINING A LTCR PROGRAM

Where do we begin?

Who initiates the LTCR Program?

The appropriate local governing body, such as the County Commission, Parish Leaders,

City Council, Board of Aldermen, etc., should initiate the LTCR program. It is important that

local government initiates the LTCR program and supports the overall process since key

public decisions and actions will emerge from the process. Residents of the community

need to know that their elected officials are actively engaged in the LTCR planning

process and intend to follow through on resulting recommendations.

Identifying a Leader of the LTCR Program

Once the local government decides to initiate the program, the local governing board

should appoint an individual or a small group of individuals as leader of the LTCR pro-

gram. The leader will be the spokesperson for LTCR, will "kick-off" the process, serve as the

coordinator/facilitator at the community meetings, and establish partnerships with local,

state, and federal organizations and agencies. The leader can come from the local govern-

ment or from the community at large. In either case, the leader should be someone who

has the respect of the community and whose lead the community will follow in establish-

ing a LTCR program. This leader should work hard to unify rather than divide the commu-

nity on future recovery actions.

Leadership is a critical step in the LTCR program. A good leader will serve as a beacon for

community and government involvement and will convey the importance of the recovery

process to local, state, and federal officials. A good leader will draw others into the LTCR

program and solicit individuals to serve as champions for specific projects that evolve

from the process. A good leader will make sure that all community members are given an

opportunity to participate in the LTCR program and will assure that the LTCR plan and

projects focus on the community vision for recovery from the disaster.

Communities may want to consider two leaders - one to manage the day-to-day aspects

of the LTCR program (possibly a community Planning Director, County Administrator, City

Manager, etc.) and one to serve as the visible, public face of the program (mayor, chief

elected official, or community leader) who will work together to carry out the program.

Establishing a LTCR Team

There is an advantage to establishing a planning team with broad public and private sec-

tor representation that can function as a sounding board for the LTCR program leader and

provide routine input into the overall recovery process. Such a team does not replace the

community involvement process but can often provide realistic guidance as the process

moves forward. A LTCR team should not be too large. Consideration might be given to

representatives from the following organizations for membership:

• Public Works Department

• Public Information Office

• Planning Department

• Emergency Management/Local Mitigation Coordinator

• Chamber of Commerce

SELECTING AN OVERALL LEADER AND OUTLINING A LTCR PROGRAM • STEP 2

16 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Chapter II

Step 2

Selecting an Overall

Leader and Outlining

a LTCR Program

LTCR

• Homebuilders Association (if housing is an issue)

• Neighborhood representation

• Environmental groups

• Critical Industries

• Citizen at Large

• An elected official from the community

governing body

• Public health and/or medical community

representative

• Voluntary agency representative

This LTCR team is likely to be comprised of people

who already are involved in the hazard mitigation and

comprehensive planning processes.

It is important that this planning team be used as a

sounding board for ideas. This team should not delay

the process but should facilitate issue and project

identification, provide assistance in the community

involvement process, help author the plan, and assist

in finding project champions. The team should not be

asked to provide a stamp of approval to the LTCR plan

but should seek community consensus on the plan

and eventually submit the plan to the governing body

for their approval and implementation.

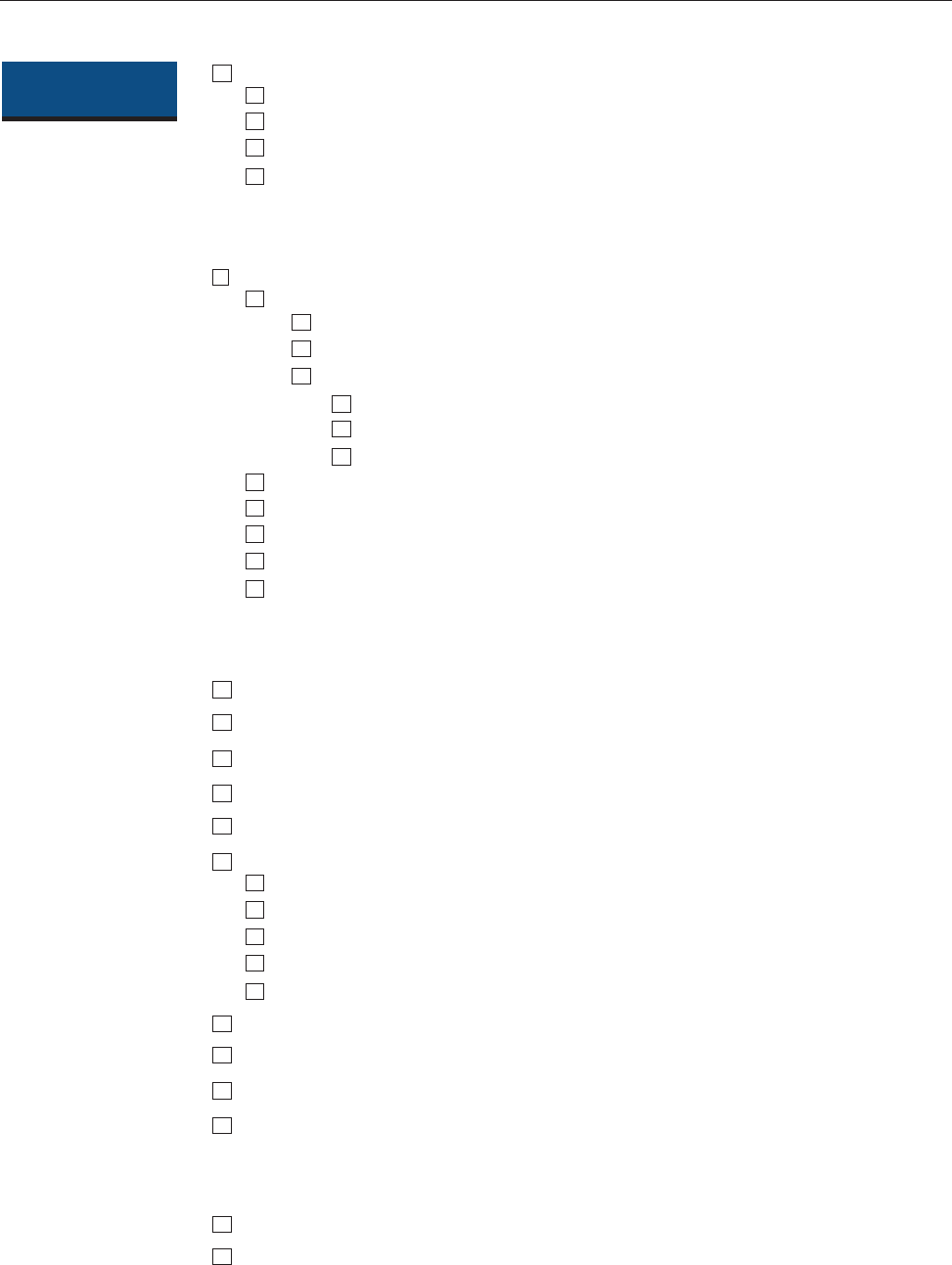

Components of a LTCR Program

The individual components of a LTCR program are

detailed and discussed in ensuing sections of the

guide and illustrated in Figure 2. The LTCR program

contains the following components:

• Securing outside support

• Establishing public information and involvement

program

• Achieving consensus

• Identifying opportunities

• Articulating a vision and setting goals

• Identifying, evaluating and prioritizing projects

• Developing a recovery plan

• Choosing project champions

• Developing a funding strategy

• Implementing the plan

• Updating the plan

LTCR Planning Time Frame

Generally, the LTCR planning activities should be initiated 4 to 8 weeks after a disaster and

be completed within 6 to 12 weeks depending on the severity of the damages and the

STEP 2 • SELECTING AN OVERALL LEADER AND OUTLINING A LTCR PROGRAM

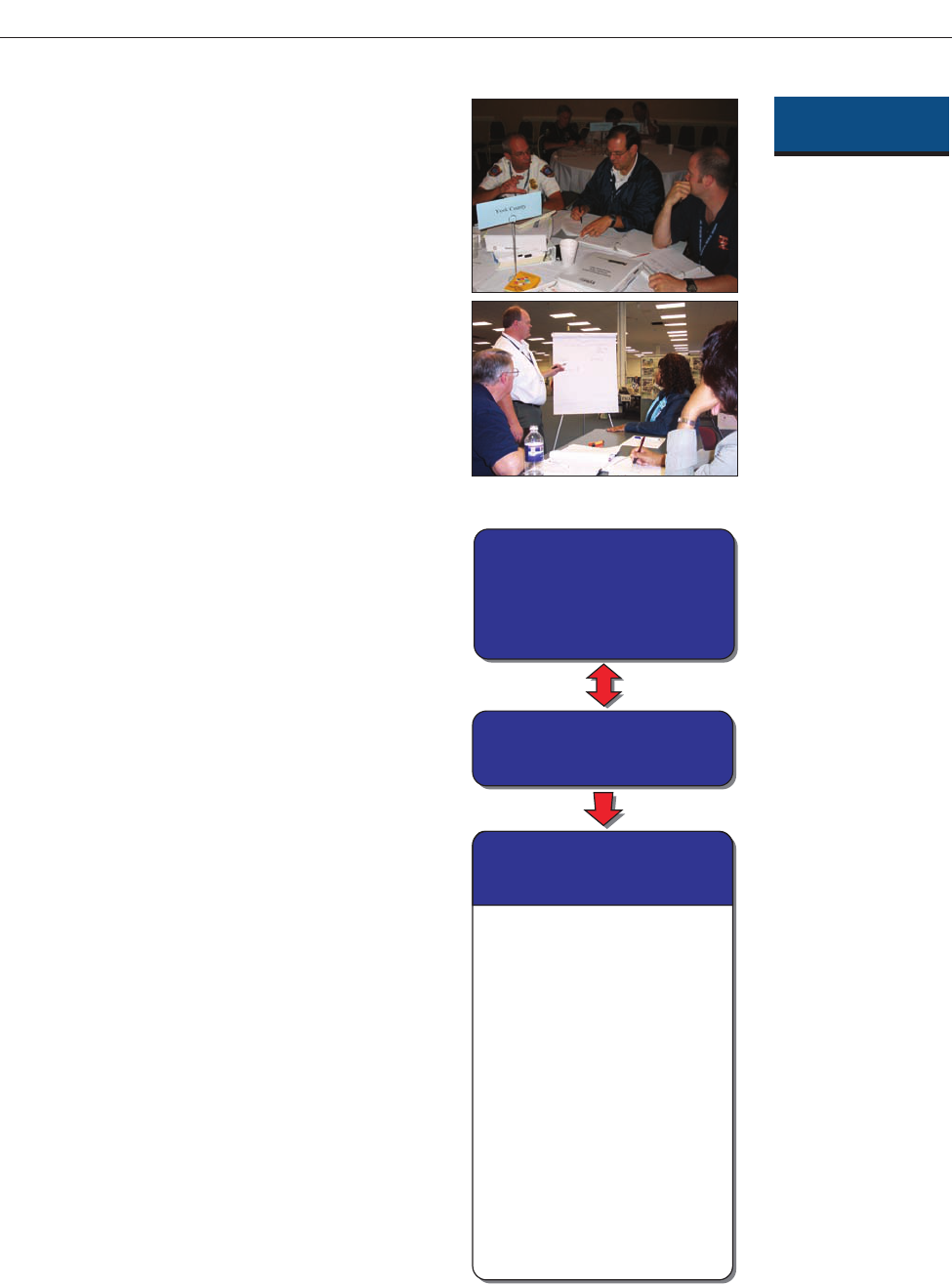

FEMA

Conducts needs assessment

Meets with local government

partners to discuss needs assessment

results and transmits Self-Help Guide

1.

2.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

(city, county, state, tribal authority)

Long-Term Community

Recovery Program

Identify and choose a leader

Establish a planning team

Secure outside support

Establish a public

information campaign

Achieve consensus

Identify LTCR issues

Articulate a vision

Identify, evaluate and

prioritize LTCR projects

Develop a plan

Choose project champions

Funding strategy

Implementation

Update the plan

Figure 2

LTCR Steps

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 17

LTCR

SELECTING AN OVERALL LEADER AND OUTLINING A LTCR PROGRAM • STEP 2

resources available. Initiating and completing the LTCR planning process in a relatively

short time frame is important in order to capture the cooperative community spirit that

usually exists immediately following a disaster and to take advantage of the attention

(and funding opportunities) provided by federal and state agencies. Although this

process has been carried out by experienced LTCR planning teams within the 6-12 week

time frame, it may take longer for a community without experience in the process.

Summary

The LTCR leadership is critical to the overall process. The local government must initiate

the LTCR program, select a leader and support the program.

Chapter II

Step 2

Selecting an Overall

Leader and Outlining

a LTCR Program

18 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

LTCR

STEP 2 • SELECTING AN OVERALL LEADER AND OUTLINING A LTCR PROGRAM

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 19

LTCR

STEP 3:

SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT

Where can we get help?

You Can't Do This Alone

The LTCR program will be much more effective if the community reaches out to local,

state, and federal agencies, the private sector and non-governmental organizations to

establish partnerships in the recovery process. Involving various organizations and agen-

cies in the LTCR program will eventually help to establish project "ownership" at the

agency level. Establishing ownership can facilitate support during the implementation

process when funds or technical assistance may be needed. Support from these organiza-

tions and agencies should not be limited to funding but should include ideas, insights,

time and energy. Experts in these groups may be willing to offer free advice or assistance

while others may be willing to share their insights and experiences.

Who Can Help Us?

There are a number of local, regional, state, and federal organizations and agencies that

may be able to provide assistance in a community's long-term recovery efforts. In many

cases, organizations and agencies may be eager to provide assistance following a disaster

but need to be invited to become involved.

The following represent some of the agencies, organizations, and institutions that a com-

munity should consider involving in the LTCR program. Figure 3 illustrates the relation-

ship of the outside support to the LTCR process and steps.

• County government agencies - Can any county government agencies provide

assistance? Does the county have greater resources than your community and

could it partner with you in the recovery process?

• Metropolitan Planning Organization - Is there a Metropolitan Planning

Organization (MPO) in your area that coordinates transportation planning?

Include them in your recovery planning efforts, especially if there are

transportation infrastructure needs or issues to be addressed.

• Regional Planning Commission - Does the community participate in the

activities of the Regional Planning Commission (RPC)? Is it a member? RPCs may

have outreach programs for their member communities or may be able to

provide technical assistance with project development or grant writing and

project funding identification.

• State agencies - The state will have several agencies that can provide assistance

and be partners in the recovery process. Each state will have different

department designations and organizations, but these types of agencies should

be considered:

•

Governor's Office

•

Department of Administration

•

Department of Economic Development

•

Department of Housing or Community Development

•

Natural resources or environmental agency

•

State emergency management agency / State Hazard Mitigation Officer (SHMO)

•

Department of Transportation

•

State public health organization

•

Department of Agriculture

•

State historic preservation office

•

Private foundations that emphasize projects within the state

Chapter II

Step 3

SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT • STEP 3

20 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Chapter II

Step 3

Securing Outside

Support

LTCR

• Federal Agencies - Similar to the state, the federal government has a number of

agencies that could be potential partners in the recovery process. Here are a few

to consider involving in the LTCR program:

•

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

•

Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

•

Economic Development Administration (EDA)

•

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

•

USDA-Rural Development

•

National Oceanic &

Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA) - Ocean and Coastal

Resource Management

(OCRM)

•

Resource Conservation and

Development Councils

• Adjacent communities and/or

counties - Are there larger

communities or counties nearby

that you can collaborate with on the

LTCR plan? Do they have resources

they would be willing to provide as

part of the LTCR program? These

communities/counties are often

willing to donate staff time to a

neighboring community's recovery

efforts.

• Professional Organizations -

Depending on the specific needs of

your community, a professional

organization may be able to provide

planning resources and/or possible

project funding for the LTCR

program. Many of these

organizations have local or state chapters that could be involved in your LTCR

program or provide expertise in a particular area. Some of the organizations that

may be of assistance include:

•

International City Manager's Association (ICMA)

STEP 3 • SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT

EMERGENCY SUPPORT FUNCTION #14

Emergency Support Function #14 (ESF #14), Long-Term Community Recovery and

Mitigation, has been established to address recovery issues from a comprehensive

perspective following an incident of national significance. Under the National

Response Plan, ESF #14 coordinates the resources of federal departments and agen-

cies to support the Long-term community recovery of states and communities, and

to reduce or eliminate risk from future incidents. ESF #14 is led by FEMA and sup-

ported by the following primary agencies, including the Departments of

Agriculture, Commerce, Housing and Urban Development, Treasury, and the Small

Business Administration. A number of other agencies serve in a support role. The

state can also assist in identifying those federal agencies that would be of assis-

tance in your particular recovery effort.

FEMA REGIONAL OFFICES

FEMA has ten regional offices. Each

region serves several states to help

plan for disasters, develop mitigation

programs, and meet needs after major

disasters. The following is a web site

reference for FEMA regional offices:

www.fema.gov/regions

FEMA LONG -TERM

COMMUNITY RECOVERY

Long-term community recovery (LTCR)

takes a holistic, long-term view of criti-

cal recovery needs, and coordinates

the mobilization of resources at the

federal, state, and community

levels.The following is a web site refer-

ence for LTCR:

www.fema.gov/rrr/ltcr

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 21

Chapter II

Step 3

Securing Outside

Support

LTCR

•

Urban Land Institute (ULI)

•

American Planning Association (APA)

•

American Institute of Architects (AIA)

•

American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA)

•

State Municipal League

•

State Association of Counties

•

Association of State and Territorial Health Organization (ASTHO)

•

National Association of City and County Health Officials (NACCHO)

• Educational Institutions - Is there a college, university, or community college in

the area that has departments or centers that could facilitate the LTCR program?

Many educational institutions have community outreach programs that may be

of assistance. Some educational institutions also may be willing to expand their

curriculum to accommodate a new area identified in your LTCR plan.

• Private Sector - large businesses, employers, benefactors

• Other Non-Profit Organizations

•

Extension service

•

State rural development council(s)

•

Faith-based organizations

•

Community development corporations

Coordination of Support

Any outside support will require coordination. There are several ways to coordinate out-

side support depending on the specific needs of the community and the scope of the

LTCR program. Some of the methods for coordinating support include:

• Inviting key agency staff to become members of the LTCR team. This assures that

you have the opportunity to receive their input on key issues but also inserts

them into the process and gives them a stake in its outcome, which may be

beneficial when technical, political, or financial assistance is needed for

implementation of the LTCR plan.

• Establishing weekly/regular conference calls for all outside support member

participation. This could constitute a support team task force that could be kept

apprised of the status of the process and asked for input regarding key steps in

the overall program.

• Establishing weekly/regular meetings if the support is local. This can function in

much the same way as the above support team task force but has the advantage

of face-to-face interaction.

• Inviting all appropriate organizations and agencies to the community meetings

to both solicit their input and to allow them to see the community involvement

process and community support for the LTCR program. This action also continues

to involve the media support for the LTCR process.

• Consider scheduling a "Community Recovery and Resource Day" where all local,

regional, state, and federal organizations and agencies (public and private) are

invited. Use this event as an opportunity to present the community needs, issues,

draft plans and projects and request their input, assistance, and especially

partnership in making the LTCR program successful.

SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT • STEP 3

22 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Chapter II

Step 3

Securing Outside

Support

LTCR

STEP 3 • SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT

ITEMS TO CONSIDER WHEN DEVELOPING A COMMUNITY

RECOVERY AND RESOURCE DAY WORKSHOP:

1. Local communities should identify and invite state, federal, and other

resource agencies or entities (Trust for Public Land; Habitat for Humanity,

Transportation entities, Congressional staff members; etc.) to participate.

Use existing agency contacts to seek out other potential attendees.

2. Local project stakeholder participants should include administrative,

regulatory, and technical staff.

3. The workshop forum should be informal and in a setting that will allow

discussion and brainstorming among all parties. The meeting space should

be arranged for all parties to interact. For example, a horseshoe shaped

table arrangement will allow face-to-face contact for discussion as well as a

focal point for presentations.

4. Allow at least several weeks advance notice when scheduling a workshop

to ensure adequate attendance by the participating agencies.

5. Advertise the workshop as a one-day event, but provide enough time at

the beginning and end of the meeting for people to commute to and from

the workshop, especially when considering the location of state and federal

agency offices (For example, schedule the workshop from 10:00 a.m. until

4:00 p.m.).

6. The forum process and agenda should be clearly defined for participants

prior to the meeting. Emphasize the informal dialogue and networking

opportunity

7. Schedule the meeting date to coincide with a local event, activity or

festival. This will provide an incentive for attendees to attend the

workshop.

8. If possible, include meals and snacks on-site to maximize workshop

effectiveness and to facilitate additional networking or discussion.

9. If possible, include a tour of proposed projects or sites to allow participants

to experience the project or setting in person.

10. Don't ask for money from prospective partners! Instead, build relationships

that will extend well beyond a meeting or workshop. Request ideas,

suggestions and solutions to project challenges. Seek partnerships and

assistance - technical, organizational, regulatory and financial.

11. Provide a meeting summary for all participants.

12. Host a Resource Day on a regular basis (semi-annual, annual, biannual, etc.)

depending on scope and nature of the project(s).

13. Be patient and accept that the process takes time - even disaster recovery.

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 23

Chapter II

Step 3

Securing Outside

Support

LTCR

Focus on Community Needs

Keep the community's needs and issues in mind when securing outside support. Be selec-

tive, but thorough. Don't involve the state department of transportation if there are no

transportation needs or issues. On the other hand, if housing rehabilitation in the older

area of town is a need and an issue, make sure that you not only involve the state's hous-

ing agency but also the historic preservation office, the community development agency,

etc. Various state programs may be needed to bring a project to fruition.

Keep Your Partners in the Loop

Make sure all your partners inside and outside the community are kept current and up to

date on the status of the LTCR program. Use phone calls, meetings, status reports,

newsletters, as a means to keep them connected to the process. When needed, be sure to

solicit their input on steps in the LTCR program - don't just send them information. You

have involved them because they can be of assistance to your recovery. Use them.

SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT • STEP 3

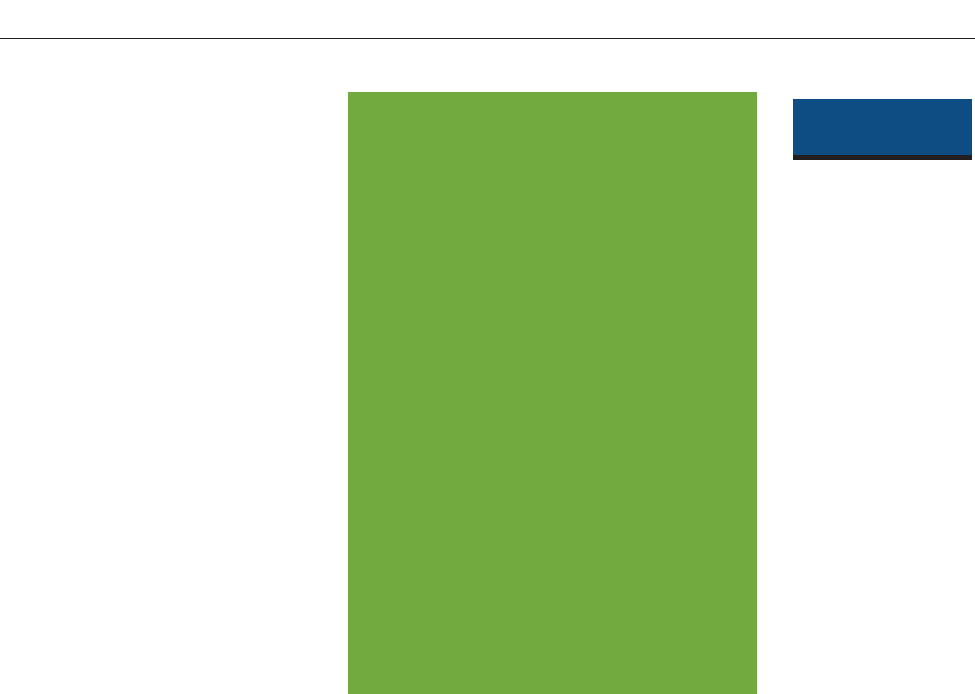

FEMA

Conducts needs assessment

Meets with local government

partners to discuss needs assessment

results and transmits Self-Help Guide

1.

2.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

(city, county, state, tribal authority)

Long-Term Community

Recovery Program

Identify and choose a leader

Establish a planning team

Secure outside support

Establish a public

information campaign

Achieve consensus

Identify LTCR issues

Articulate a vision

Identify, evaluate and

prioritize LTCR projects

Develop a plan

Choose project champions

Funding strategy

Implementation

Update the plan

POTENTIAL AGENCY & ORGANIZATIONAL SUPPORT

County Government Agencies

Metropolitan Planning Organizations

Regional Planning Commissions

State Agencies

Economic Development

Natural Resources

Environment

Emergency Management /

Hazard mitigation

Administration

Governor's Office

Transportation

Housing

Community Development

Historic Preservation

Health

Agriculture

Federal Agencies

FEMA

HUD

EDA

EPA

USDA - Rural Development

NOAA - OCRM

Adjacent Communities / Counties

Professional Organizations

ICMA

APA

ULI

AIA

ASLA

State Municipal League

State Association of Counties

Educational Institutions

Private Sector and Non-Profits

LONG-TERM

COMMUNITY RECOVERY

PROGRAM

LTCR Steps and Outside Support

Figure 3

LTCR Steps and Outside Support

24 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Chapter II

Step 3

Securing Outside

Support

LTCR

STEP 3 • SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT

Case Study

North Central Illinois Council of Governments

Securing outside support is a multi-faceted objective that should be tackled from

several directions. Involving the Council of Governments (COG) in your region can

be a very productive outreach effort. After a destructive tornado hit the Village of

Utica, Illinois,in April 2004, the LTCR team elicited the support of the North Central

Illinois Council of Governments (NCICG). NCICG is a non-profit planning organiza-

tion that supports local governments by providing planning, technical assistance,

and grant writing services for communities like Utica, where many local officials are

part-time. NCICG had provided planning services to Utica in the past. They knew

the local officials and key stakeholders, understood the state agency framework and

contacts, and held the planning-related documents for Utica and the region's com-

munities. The success of the LTCR process would depend on securing support from

this group.

The connection between the LTCR team and the NCICG staff was encouraging from

the start. NCICG Executive Director Nora Fesco-Ballerine brought boxes of planning

and environmental documents to help inform the LTCR team about regional growth

strategies, environmental concerns, and existing projects. Kevin Lindeman, senior

planner at the NCICG, supported the LTCR team by sharing his experiences in devel-

oping the Utica Comprehensive Plan and providing technical assistance as projects

were identified. Because the NCICG had experience in grant writing, they also

helped the LTCR team communicate with state and federal agency representatives

in charge of grant programs. Without the pivotal support of the NCICG, the Utica

United Recovery public planning process would not have been so successful. And

with their hands-on involvement in the LTCR process, NCICG staffers were able to

push the plan into the implementation phase by writing grants and securing dollars

for identified project.

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 25

Chapter II

Step 4

LTCR

Step 4:

ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN

How do we keep the community informed and involved in the process?

Why do we need a public information campaign?

The LTCR plan's success depends on the extent of community involvement. The goal of a

LTCR public information campaign is to get community members involved in the process,

while the challenge is to focus attention on long-term planning for the community when

many individuals' long-term circum-

stances may be unclear.

It is easy to become caught up in the

LTCR effort and neglect the community

involvement aspect until it is too late.

Often, community members' and com-

munity leaders' visions are similar and,

because no discernable gap is apparent,

a strong public information strategy

may not seem important.

Should we appoint an official

Public Information position?

It is useful to appoint one person to

carry out the public information cam-

paign. However, this decision is

dependent on your budget, the scope

of the LTCR effort and the size of your

community. A LTCR team member or

public/private volunteer can be consid-

ered for this role. The importance of this

role increases as the scale of the LTCR

effort increases.

It is useful to appoint someone who can

work efficiently and creatively with min-

imal oversight. This position is different

from the rest of the team because with

it comes the unique responsibility of

conducting an informational campaign

targeted to all members of the commu-

nity - many of whom have never attend-

ed a public meeting. The person in this

role should develop a strategy tailored

to the community's LTCR effort. In addi-

tion, the role requires excellent oral and

written communication skills to write

press releases, answer media inquiries,

and respond positively to media and

community member criticism.

ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN • STEP 4

PUBLIC INFORMATION

CAMPAIGN

Committing to the public information

campaign early and fully ensures a suc-

cessful plan by:

• Giving community members a

chance to develop their own

vision for the future of the

community and transcend

individual issues - it gives them

hope for the future and

empowerment for the present

• Establishing a high LTCR

profile, which may bring issues

to the forefront and increase

the possibility of garnering

funding

• Encouraging the community

to take ownership of the plan

and expect results - even after

the LTCR team is finished

• Making it easier to find project

champions and funding

• Prioritizing projects in the LTCR

plan

• Establishing community 'buy-

in' to the plan and the process

• Clarifying that the plan is

indeed driven by community

members - and not by outside

parties who may have another

agenda

26 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Chapter II

Step 4

Establishing A Public

Information

Campaign

LTCR

Establishing a vision

Many community members may be overwhelmed and inundated with information after a

disaster - this drives the need to keep the public information campaign simple and

straightforward, and to establish an early vision. Public information materials should have

a consistent look and feel to help distinguish this effort in the community. These materials

might consist of the following elements:

• Choosing a slogan for the LTCR effort, for example "Your projects.Your future. Get

involved."

• Communicating a consistent message

• Emphasizing this is the community's plan

• Explaining the purpose of LTCR

Make local media partners in the process

It is critical to establish positive relationships with a variety of media sources and to con-

sider them partners in the public information campaign. Keep the media informed

throughout the process. A strong media presence will put the LTCR effort in the public

spotlight and encourage strong community participation. Past LTCR efforts received such

strong support from the media that aver-

age meeting attendance hovered around

600 people.

LTCR efforts usually receive excellent cov-

erage from major local newspapers with

many front-page stories. Newspapers

were the most useful supporters in past

LTCR efforts and provided excellent cov-

erage of the community meetings. Also

be sure to establish relationships with

small local newspapers that are distrib-

uted on a weekly or monthly basis. Local

papers often support the LTCR planning effort by offering free advertising space and

opportunities for interviews.

Getting the message out

The scale of your communications strategy will not only depend on the size of the com-

munity and scope of your LTCR effort, but also on your budget. This section suggests a

variety of options intended to inform the community and motivate individuals to attend

LTCR community meetings. The options vary in price from free to several thousand dollars

- market rates can often be negotiated.

People or groups that may be of assistance

• LTCR Team - The LTCR team is an excellent resource and must be tapped to reach

out to community leaders, organizations and associations. Since the team will be

meeting with these parties, members must come equipped with communication

materials and available meeting dates. An example may include an informational

packet regarding LTCR.

STEP 4 • ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 27

Chapter II

Step 4

Establishing A Public

Information

Campaign

LTCR

• Mass Retailers - Flyers are most easily distributed through mass means. Large

chain stores (i.e., Lowe’s, Home Depot, Wal-Mart) are often willing to distribute

flyers.

• School System - Past efforts also found the school superintendents' offices to be

very cooperative and willing to send home a flyer with each child in the public

school system.

• Chambers of Commerce - Local Chambers of Commerce are useful sources for e-

mail blast lists and may be of assistance in recruiting the support of local

business owners.They may be willing to add an update corner in their

weekly/monthly newsletter. Flyers also could be attached to the mass e-mails so

local business owners can put them in their windows.

• Volunteers - Often, volunteer assistance may be recruited from sources such as

community colleges or retirement communities.

• Organizations, associations and faith-based groups - Assistance may be

recruited from local organizations, civic associations and faith-based groups.

Communication mediums

• Newspapers - Past, large-scale LTCR

efforts conducted advertising

campaigns to get people to the

LTCR community meetings. To

further this goal, 2 newspaper

inserts were placed in the major

newspaper in each county: 1) a

listing of all

suggestions/recommendations

made during the LTCR community

meetings, and 2) the rough-draft

LTCR plan. Both inserts included an

email and physical address to mail

comments.

• Blast Fax / Email Lists - Each team

member should ask every contact if

he/she has access to a fax or email

blast list - these are invaluable for

getting the community leadership,

activists and business owners

involved in the process.

• LTCR Mailing List - Use the team to assist in the development of a contact list

that includes each person or group each member met with. Email this list before

every meeting.

• Radio - Radio often offers a variety of free opportunities to advertise workshops

and may also be interested in conducting interviews with community leaders and

LTCR team members. If time permits, it is useful to write copy for a 15 second, 30

second and 1 minute radio time.

ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN • STEP 4

Example of Newspaper Insert

28 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Chapter II

Step 4

Establishing A Public

Information

Campaign

LTCR

• Flyers - Flyers advertising the

community meetings also are

beneficial and may be distributed

through the channels mentioned

above. It is best to keep the flyer

message simple and concise.

• Internet - The Internet is a great

tool to supplement your advertising

efforts. Since the PR message must

be kept simple, establishing a web

site would provide an excellent

additional information source to

your marketing campaign.

• Office open house - If you are

fortunate enough to have a

separate LTCR office, stage a grand

opening for the press and local

community members. Include

informational packets for the press

and display past LTCR plans.

• Television - The local cable access

channel and local news channels

are often interested in participating in the LTCR events or conducting interviews

and usually request to be kept updated with current information.

• Newsletters - utility providers, organizations and governmental entities

Reaching minority groups

It is essential to reach minority and/or low-income groups who represent a significant part

of the population, especially if their native language is not English. These groups rarely

participate in public meetings but are often affected by the projects proposed in the LTCR

plan. Their voices need to be heard. They are often reached via radio stations, by placing

flyers at shops they frequent, or through faith-based groups and churches.

How do we respond to criticism?

The LTCR effort may encounter criticism from various sources. The best defenses against

this are to keep the press updated on the LTCR efforts and to wage a successful PI cam-

paign that results in high attendance at the LTCR community meetings. While past LTCR

efforts faced media challenges, the effort was almost always fully supported after a high

resident turnout at the community meetings - when attendees realize that the plan is

truly driven by the community.

You can expect some community members to speak out against components of the LTCR

effort. When this occurs, it is useful for the LTCR team leader and appropriate team staff to

meet with these community members individually. While this may not resolve all issues, it

will clear up any misunderstandings about the LTCR mission.

STEP 4 • ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN

Example of Community Flyer

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 29

Chapter II

Step 4

Establishing A Public

Information

Campaign

LTCR

ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN • STEP 4

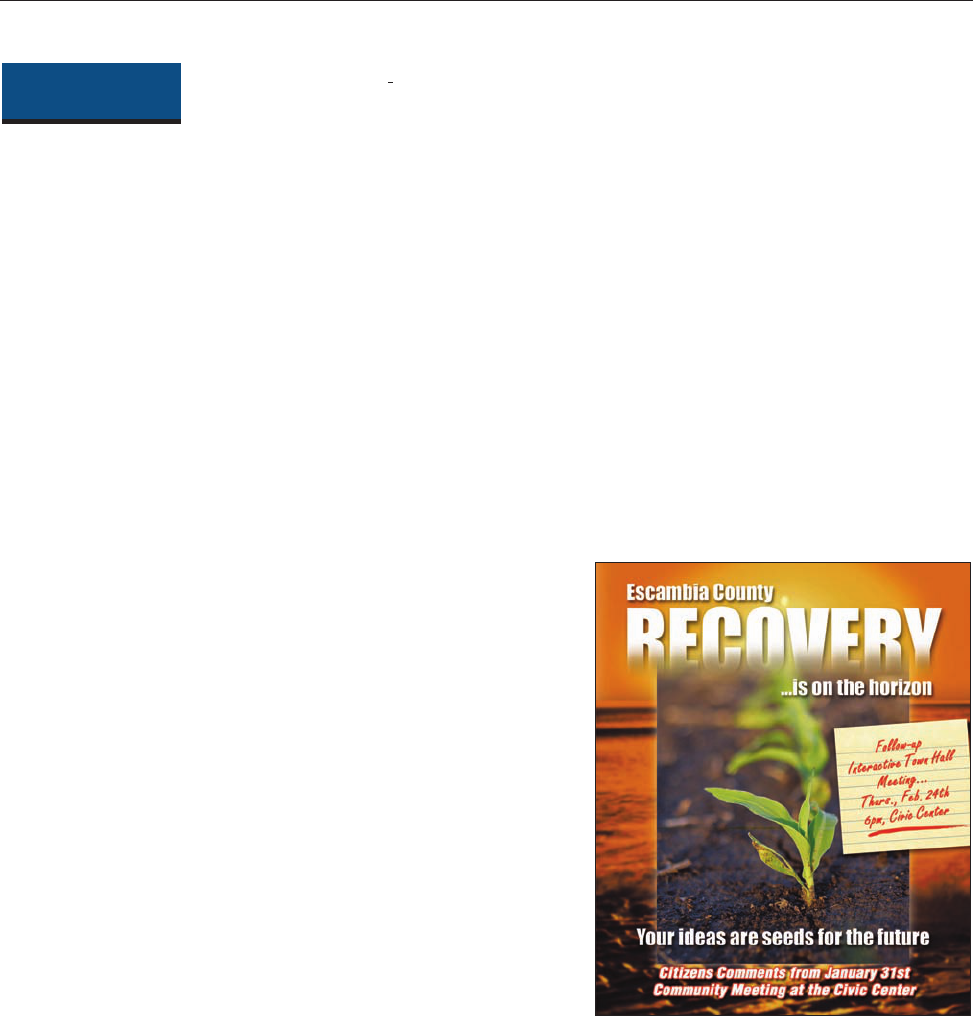

Case Study

Public Information Campaign - Santa Rosa County, Florida

Hurricane Ivan struck Santa Rosa County in September of 2004 and damaged or

destroyed just over half of its 44,000 housing units. Post-disaster, residents were

inundated with information and the Public Information Campaign needed to be

focused and concise. The campaign consisted of two distinct phases - meeting one

and meeting two. Since the first meeting had relatively low turnout (approximately

300 people), the campaign changed its strategy for the second meeting, which

resulted in a tripling of attendance.

The preparation for the first meeting included many initiatives: the opening of a

LTCR storefront to encourage citizen walk-ins; keeping newspapers up-to-date via

press releases; distribution of flyers by large chain-stores and the public school sys-

tem; emailing blast lists; and conducted limited grass-roots marketing. The newspa-

per advertising campaign included a somewhat busy half-page advertisement that

focused on informing the public, rather then getting them to the meeting. This

made for lengthy copy and added to residents' information overload. The effort

received excellent newspaper attention overall and was mentioned on the front

page the day of the meeting. However, attendance at the first meeting was low, and

the team was concerned that it would not have enough public support behind the

plan.

The Public Information Campaign developed a new strategy following the first

meeting’s low turnout. The new strategy focused on extensive grass-roots commu-

nication and development of a simple newspaper advertising campaign with a

straightforward full-page advertisement (a one line slogan and meeting informa-

tion) in addition to an insert in the local paper detailing all the comments and ideas

obtained from the first meeting. The effort continued to receive frequent newspa-

per coverage (not all of it was positive).The flyer distribution continued, but the fly-

ers were changed to a simpler layout similar to the newspaper advertisement -

therefore adding a 'branded' element to the effort. In addition, many local business-

es agreed to put meeting flyers in their windows and a few of the large churches

announced the LTCR meeting information. Turnout tripled from the first meeting to

the second meeting.

30 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

LTCR

STEP 4 • ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC INFORMATION CAMPAIGN

LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • DECEMBER 2005 31

Chapter II

Step 5

LTCR

STEP 5:

REACHING CONSENSUS

How do we secure community buy-in to move forward?

Introduction

You've gathered data to make coherent and compelling presentations to community

stakeholders and the general public. It is time to determine which stakeholder groups

need to agree in order for the LTCR program to move forward.

Spelling Things Out

You have been building support for your LTCR program from the day you begin gathering

the data necessary for identifying the community issues and needs. Data gathering or

research is like good listening. The LTCR plan is a way of spelling out what the community

is saying and what your research has identified.

"Spelling things out" may be a step that recurs several times as part of an overall feedback

loop. You may need to go back to spell things out more than once in an effort to build

consensus among multiple stakeholder groups.

Mapping Your Network of Stakeholders

Every community includes a complex network of relationships, all of which affect whether

your LTCR program will ultimately succeed or not. Typically, that network consists of the gen-

eral public, the private sector, and government (see STEP 3: SECURING OUTSIDE SUPPORT).

But your community may have other significant stakeholder groups. Be sure to include them

in the process of building consensus.

Based on the support you've identified in STEP 4 and other community stakeholder

groups, you should consider creating a network "map" that shows all of the constituencies

that will have to be taken into account if your LTCR program is going to succeed.

Keeping the Public Involved

The public is one of your best resources,

and without the public’s support the

LTCR plan will likely fail. The advantages

of that public involvement include:

• Improved community relations;

• Learning from and informing

citizens;

• Persuading citizens;

• Building trust and allaying anxiety;

• Building strategic alliances; and

• Gaining legitimacy for decisions.

There are also benefits for citizens when they are included in a participatory process. They

include: education; increased feelings of control, helpfulness, and responsibility;

decreased feelings of alienation and anonymity; the ability to persuade and enlighten

government; and practicing active citizenship.

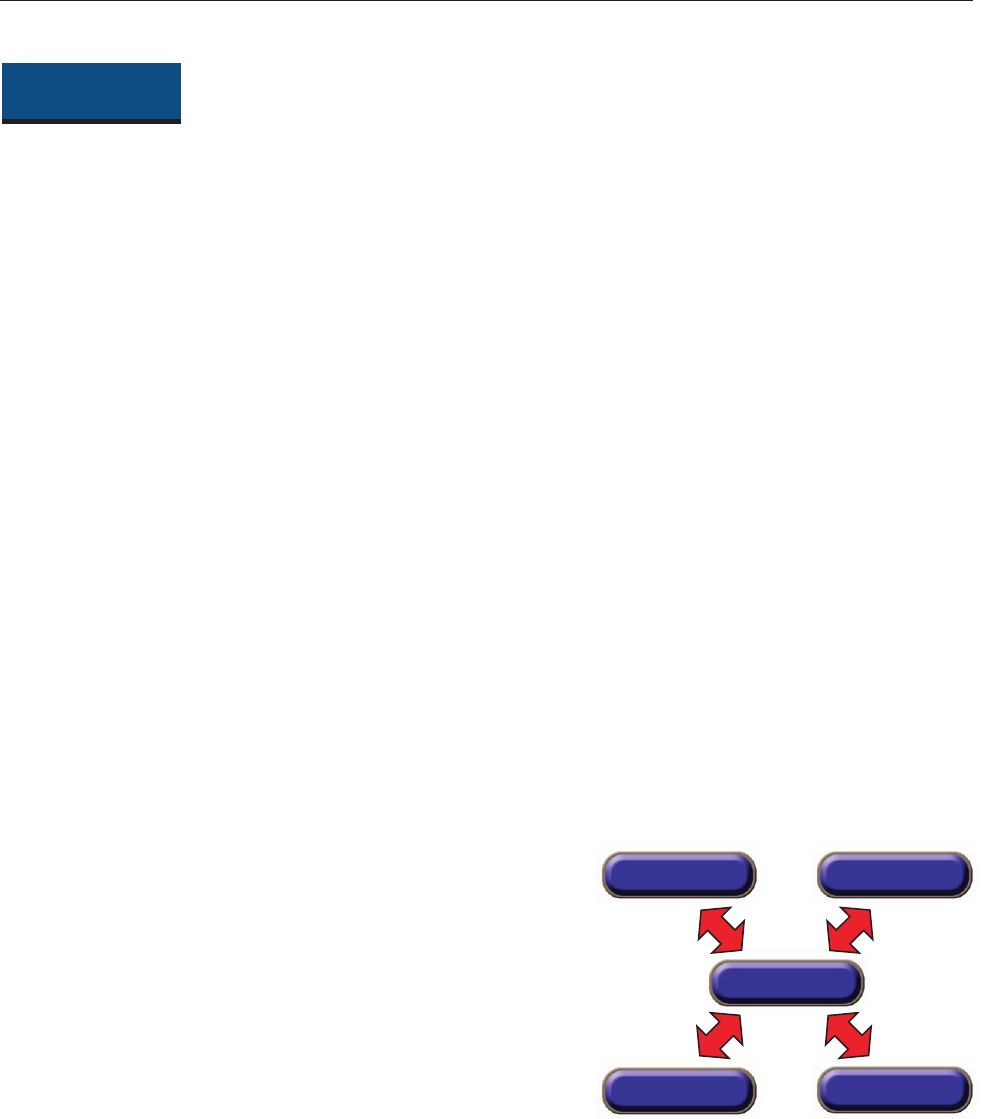

LTCR

Public

Private

Other

Government

Figure 4

Network of Stakeholders

REACHING CONSENSUS • STEP 5

32 DECEMBER 2005 • A SELF-HELP GUIDE • LONG-TERM COMMUNITY RECOVERY PLANNING PROCESS

Chapter II

Step 5

Reaching Consensus

LTCR

Aligning with Private-Sector Interests

The private sector brings extensive resources to bear along with an unwavering commit-

ment to the restoration and revitalization of the communities that support and promote

their livelihood. Businesses may also wield a great deal of political power in your commu-

nity. It is important to access their resources and consider the realities of their influence.

Working Collaboratively with Government

The State and Federal governments-beyond simply those departments or agencies that

may be directly involved in the long-term community recovery effort-offer resources

(including information and contacts). They may be able to identify linkages, overlap,

and/or gaps in proposed LTCR projects

and recommend alternative solutions

that would maximize the use of available

state and federal recovery and rebuilding

resources.

Identifying Other Stakeholder Groups

When identifying other key stakeholders

to include while building consensus, con-

sider their ties to the community, ability

to access and leverage resources, their

political influence, and their relationships

to, and potential impact on different

aspects of your LTCR program.

Reaching Out to All Stakeholders

Establish a time frame for outreach to all stakeholders that fits within the LTCR program