1

2

Contents

Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 3

Background ........................................................................................................................................................... 3

Post-Election Audit Overview ............................................................................................................................... 6

State Audit Policies ........................................................................................................................................... 7

Number of States with Post-Election Audit Laws in 2020 ................................................................................ 8

Timing of the Audit ........................................................................................................................................... 9

Traditional Audits ................................................................................................................................................ 10

Fixed Percentage Audits ................................................................................................................................. 10

Sample Sizes ................................................................................................................................................... 10

Contests Included ........................................................................................................................................... 12

Automated Audits ........................................................................................................................................... 13

Risk-Limiting Audits............................................................................................................................................. 15

Ballot Polling Audits ........................................................................................................................................ 15

Ballot-level Comparison Audits ...................................................................................................................... 16

Batch-level Comparison .................................................................................................................................. 17

Multiple Jurisdictions, Alternative Voting Methods, & Privacy ...................................................................... 17

Other Types of Post-Election Audits ................................................................................................................... 18

Tiered Audits ................................................................................................................................................... 18

Bayesian Audits ............................................................................................................................................... 18

Independent Audits ........................................................................................................................................ 19

Procedural Audits ........................................................................................................................................... 20

Project Management Planning ........................................................................................................................... 21

Training ............................................................................................................................................................... 22

Voting Systems.................................................................................................................................................... 22

Security ............................................................................................................................................................... 23

Transparency ...................................................................................................................................................... 24

Legal Considerations ........................................................................................................................................... 24

Federal law ..................................................................................................................................................... 24

State Law ........................................................................................................................................................ 25

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................... 26

Additional Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 26

3

Introduction

Election audits ensure voting systems operate accurately, that election officials comply with regulations or

internal policies, and identify and resolve discrepancies in an effort to promote voter confidence in the

election administration process. There is no national auditing standard, and methods can vary

from procedural, traditional, risk-limiting, tiered, or a combination of one or more types.

Interest in post-election audits has risen amongst the public, researchers, and policymakers in recent years.

In 2021, state lawmakers have introduced over 68 post-election audit bills in 29 states. At the time of

publication, at least nine have been signed into law.

Post-election audits are an essential component of the electoral process. This document provides

comprehensive information about election audits in the United States.

Background

The United States is unique among world democracies. There is no uniform election system under a

centralized election authority governing how elections are administered. Instead, elections are managed by

over 8,000 local governments, with unique rules and laws adopted by individual states.

Voting methods have changed significantly throughout the history of America, from voice voting to modern

computerized voting systems. Before the widespread use of voting systems, ballots were primarily cast in-

person on Election Day and counted by hand at the close of the polls on election night. Vote automation

began with lever machines in the late 19

th

-century, and by the 1960s, voting technology had progressed to

include punch cards and optical scanners. In 1965, California became one of the first states to require post-

election tabulation audits. The law required election officials to hand count ballots in one percent of

precincts that used a voting system to tally election results. The results of the hand count were then

compared with the results of the machine count, to verify the scanners counted ballots accurately. As more

jurisdictions began using modern voting technologies to count ballots, routine post-election audits gradually

expanded. However, states would not widely adopt the practice for another 50 years.

Congress passed the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA) when weaknesses of the punch card voting

system were demonstrated during the recount of the 2000 Presidential election. HAVA appropriated more

than $3.1 billion for the newly formed U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) to distribute to states to

improve election administration, including purchasing new voting systems. Consequently, over the next

decade there was a move away from paper-based and punch card voting systems and widespread adoption

of electronic voting machines.

In 2005, the Commission on Federal Election Reform, commonly known as the Carter-Baker Commission, was

formed to recommend ways to raise confidence in the U.S. electoral system.

1

In its final report, the

Commission recommended that state and local election authorities publicly audit voting machines before,

during and after Election Day, to strengthen public confidence in the accuracy of machine tallies. In 2013,

President Obama issued an Executive Order establishing the Presidential Commission on Election

Administration (PCEA). The mission of the PCEA was to identify best practices and make recommendations to

1

Building Confidence in U.S. Election, Report of the Commission on Federal Election Reform, page 28:

https://www.legislationline.org/download/id/1472/file/3b50795b2d0374cbef5c29766256.pdf

4

improve the voting experience. In its final report, the PCEA recommended that all jurisdictions audit their

election machinery following each election. The PCEA endorsed both risk-limiting audits and performance

audits.

2

At that time, the most widely deployed technology across the United States was Direct-Recording

Electronic Devices (DREs) without a Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT),

3

and less than half of states (23)

were conducting post-election audits.

As security experts raised concerns about vulnerabilities in paperless voting systems, more jurisdictions

moved away from DREs back to voting systems that use hand-marked paper ballots or paper ballot back-ups.

By 2018, according to the Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS), less than two percent of election

jurisdictions were using DREs without VVPATs.

4

This was also the first year EAVS contained comprehensive

data about post-election audits in its final report. The report showed that by 2018 thirty-eight states required

a post-election audit.

5

By 2020, just 32 jurisdictions (0.5%) reported using DREs without VVPATs and nearly 80% (44) of states

required a post-election tabulation audit to verify voting equipment used during an election correctly counts

votes. Some states like Arkansas and Michigan require an audit of election procedures. Other states like

North Dakota require an audit of its voting devices. Even when not required by law, some states like Missouri

and Nebraska conduct an audit by a formal administrative rule or guidance. Other states like Louisiana do not

statutorily require audits, but audits are conducted in all parishes.

6

Although the majority of states are conducting post-election audits, there is no national standard for how

post-election audits should be structured. In August 2021, the National Association of Secretaries of State

(NASS) issued the first of its kind national recommendations for post-election audits.

7

The following are the

recommendations from the NASS Task Force on Vote Verification pertaining to post-election audits:

• States should have a requirement and timeframe, ideally in state statute, for post-election audits in

place prior to an election. These defined requirements should include conducting the audit as soon

as reasonably possible after an election, as well as a process to recertify election results based on the

results of the audit.

• Ensuring chain of custody procedures throughout the post-election audit process is paramount.

Election officials should be able to track the movement and transport of ballots, voting machines,

and other election materials through witnesses, signature logs, security seals, video, etc. A break in

the chain of custody increases the risk that the integrity or reliability of the asset cannot be restored.

The EAC Chain of Custody Best Practices document and

CISA Chain of Custody and Critical

Infrastructure Systems document should be used as a reference when establishing these procedures.

2

Presidential Commission on Election Administration Final Report, page 66:

https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/eac_assets/1/6/Amer-Voting-Exper-final-draft-01-09-14-508.pdf

3

2014 EAVS Report, page 14 :

https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/eac_assets/1/1/2014_EAC_EAVS_Comprehensive_Report_508_Compliant

.pdf

4

2018 EAVS Report, page 21: https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/eac_assets/1/6/2018_EAVS_Report.pdf

5

2018 EAVS Report, page 22: https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/eac_assets/1/6/2018_EAVS_Report.pdf

6

2020 EAVS Report, Executive Summary:

https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/document_library/files/2020_EAVS_Report_Final_508c.pdf

7

See: https://www.nass.org/sites/default/files/Summer 2021/NASS Vote Verification Task Force

Recommendations.pdf (accessed 10/6/2021)

5

• Have state and/or local election officials be an integral part of the post-election audit process,

including in the selection of the precincts or equipment to be audited. The involvement of any third-

party entities, such as a CPA firm, should be determined by the Chief State Election Official or state

legislative act prior to an election, and those entities must work closely with election officials.

• The post-election audit methods and processes must be transparent. This includes identifying who

may observe the audit, which should include members of the public, media, political party and/or

candidate representatives. Once the results of the post-election audit are completed and certified,

they should be made publicly accessible consistent with state law.

• To avert the possibility of voting systems becoming unusable, states should have criteria in place

prior to an election for the use of a federally or a state accredited test lab to perform any audit of

voting machine hardware or software.

• States should make every effort to educate the public on their post-election audit process, as well as

other processes and procedures in place to ensure the accuracy and public trust of the results.

Although NASS issued recommendations for conducting post-election audits, there is no consensus among

election administrators or policy makers on a single audit method. As a result, state and local election

officials use a variety of methods to conduct post-election tabulation audits based on different laws,

resources, and types of voting systems.

Since its formation, the EAC has supported innovating and improving the auditability of elections. The EAC

has made grant awards totaling over $1,463,074 to county and state organizations to support research,

development, documentation, and dissemination of a range of procedures and processes for managing and

conducting high-quality pre-election audits, logic and accuracy testing and post-election audit activities.

The EAC is also charged with developing Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG) and maintains a testing

and certification program to address how voters interact with voting systems and how voting systems are

designed and developed. In February 2021, the EAC adopted VVSG 2.0,

8

which recognizes the importance of

future election equipment’s ability to support efficient post-election tabulation audits and established a new

requirement of software independence. A voting system is software-independent if an undetected change or

error in its software cannot cause an undetectable change or error in an election outcome.

9

EAC developed and adopted VVSG 2.0 to meet the challenges ahead, to replace decade’s old voting

machines, to improve the voter experience, and provide necessary safeguards to protect the integrity of the

voting process, including enhancing the auditability of voting systems. All new voting systems certified to

VVSG 2.0 will ensure votes are marked, verified, and cast as intended, and that the final count represents the

true will of the voters. To ensure integrity of the voting process, new auditability methods were developed to

detect errors through the combined use of an evidence trail and regular audits.

The ultimate goal of verifying the accuracy and integrity of elections is the same in all jurisdictions, regardless

of the type of post-election audit utilized.

8

VVSG 2.0

https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/TestingCertification/Voluntary_Voting_System_Guidelines_Version_2_0.p

df

9

Rivest and Wack, On the notion of “software-independence” in voting systems, MIT and NIST, 2006.

6

Post-Election Audit Overview

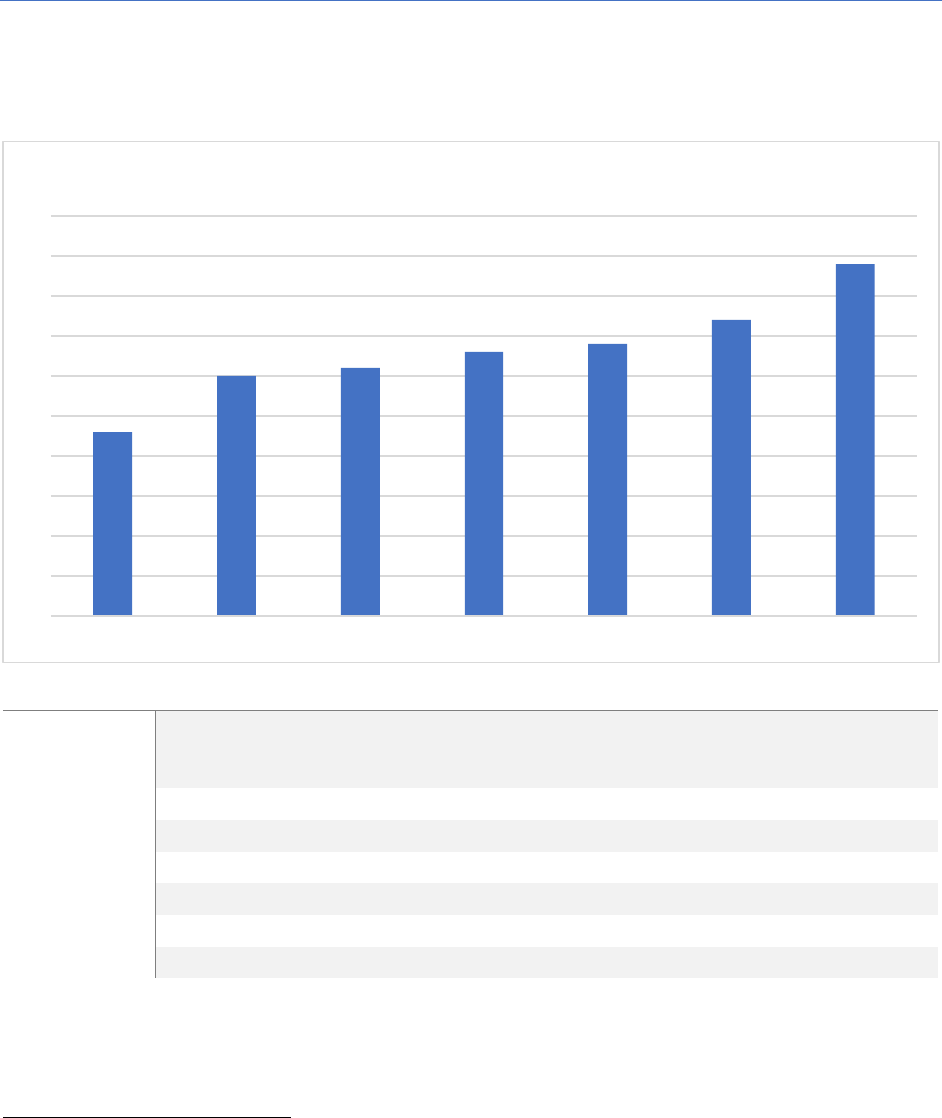

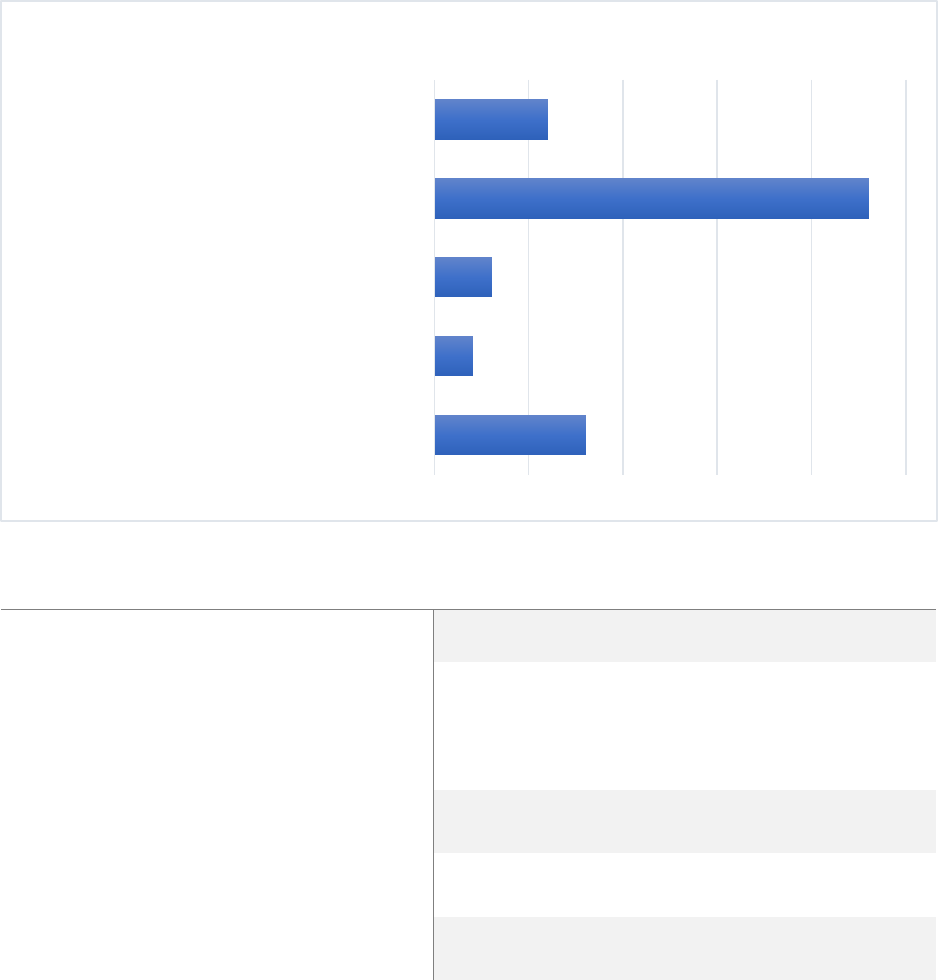

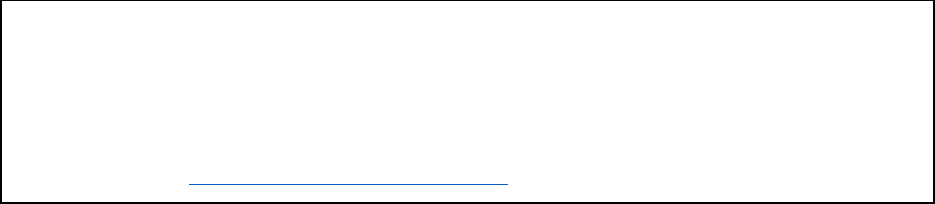

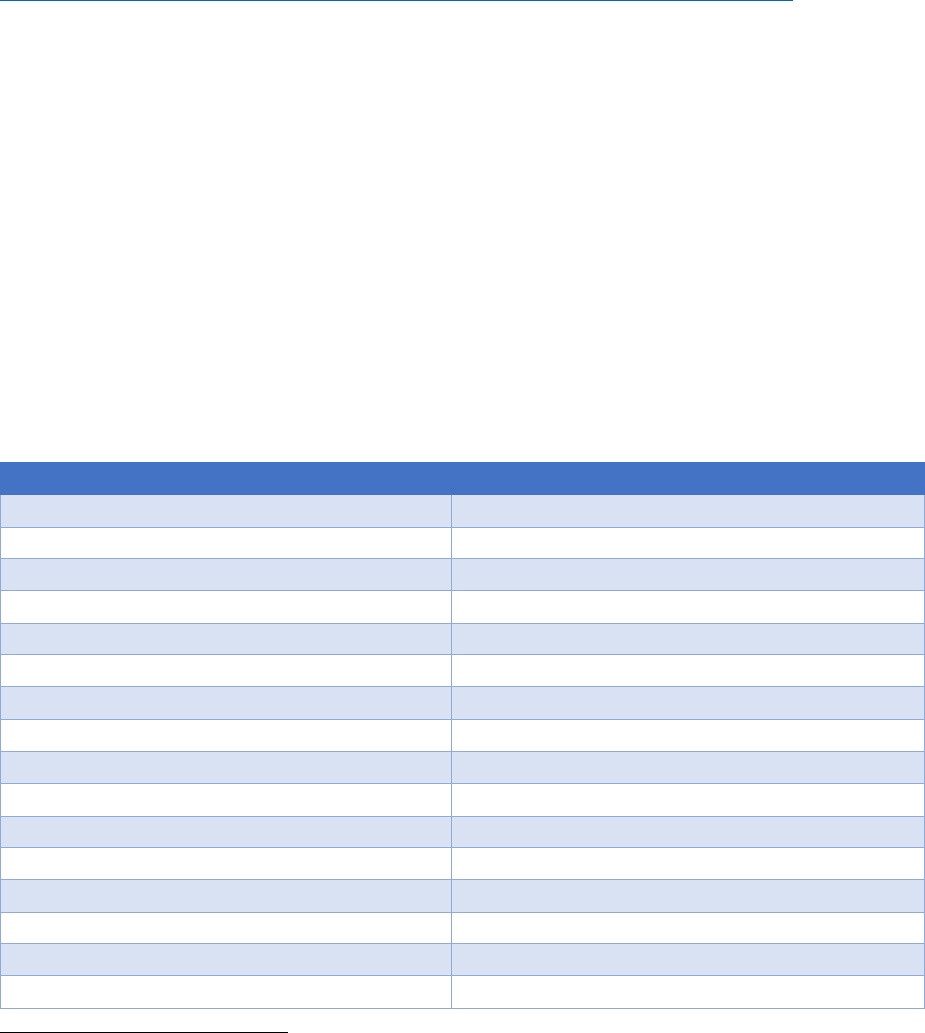

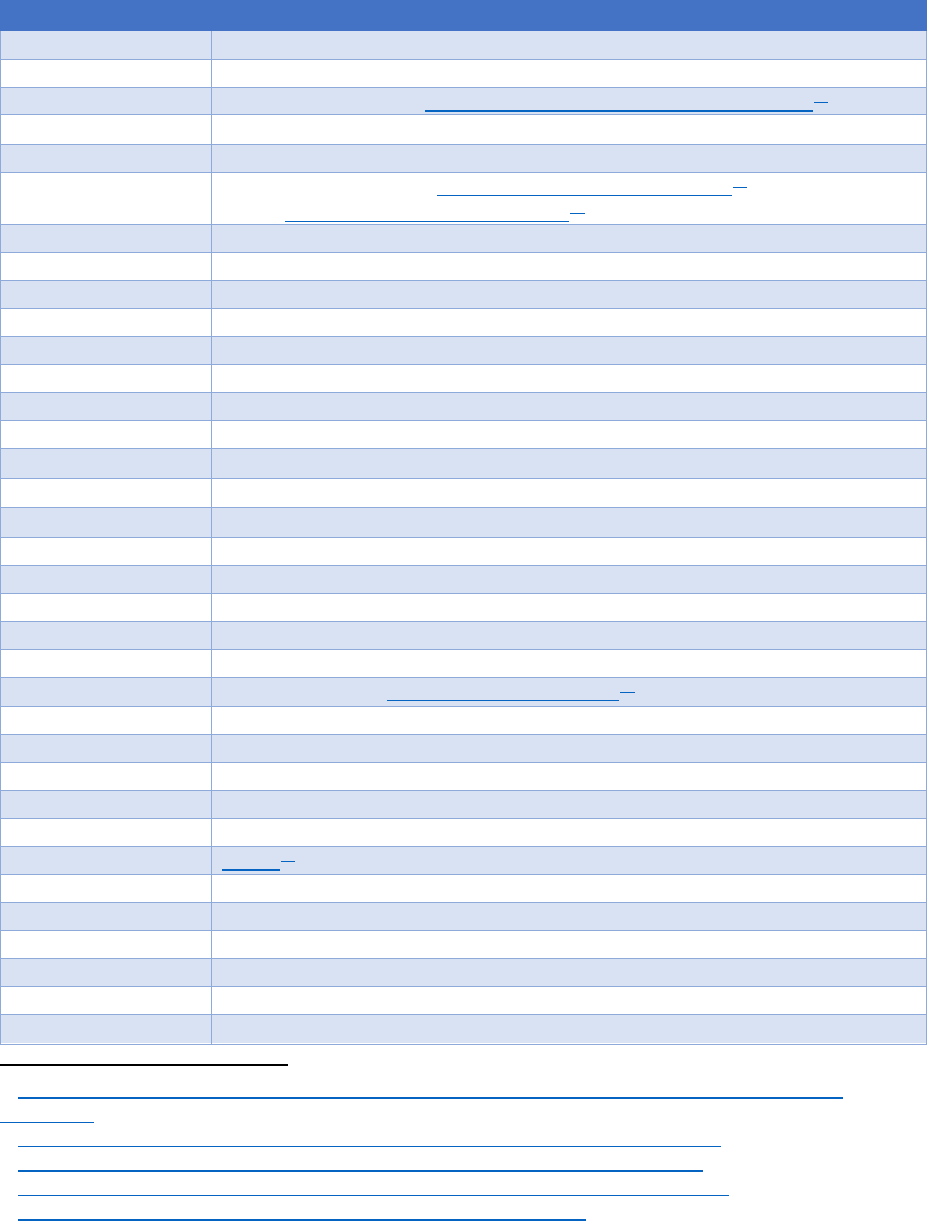

In 2008, the EAC began collecting comprehensive data about post-election audits through Statutory Overview

and Policy surveys as part of the data collection for the biennial EAVS. The chart below shows which states

reported that a post-election audit was required in each reporting year.

10

Year

States

2008

Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Florida,

Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, New York, North Carolina, North

Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin

2010

+Delaware, Hawaii, Montana, New Mexico, Ohio, Tennessee, Wyoming

2012

+Nebraska

2014

+South Carolina, Vermont

2016

+Massachusetts

2018

+Iowa, Kentucky, Rhode Island

2020

+Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, New Jersey, Oklahoma

10

Throughout this document, the District of Columbia is included when referring to the states. Information on

post-election audits in the five U.S. territories (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico,

and the U.S. Virgin Islands) was not submitted in EAVS data in all reporting years, and therefore is not included in

this document.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020

States with Post-Election Tabulation Audits

7

State Audit Policies

Post-election audit methods vary by election. The map below shows audit methods that were either required

or optional by state law in 2020. Some states also implemented additional RLA pilot programs, although it

was not mandated by statute.

State

Other & Traditional*

Idaho

*A post-election audit is only conducted when a recount is required. For federal and

statewide office - 2% of the ballots cast in each county. For all other offices or

measure - 100 or 5% of ballots cast. Requirements escalate depending on the margin

of results.

South Carolina

*The audit process compares the tabulated results of the election with the raw data

collected in the electronic audit files by each voting machine on a flashcard.

Nebraska

*Not required by statute.

North Dakota

*1% of voting system programming in each county in the state.

Wyoming

*The pre-election logic and accuracy testing is repeated after the election. A random

audit of ballots is conducted by processing the pre-audited group of test ballots on

5% of the automated tabulating machines for that county.

8

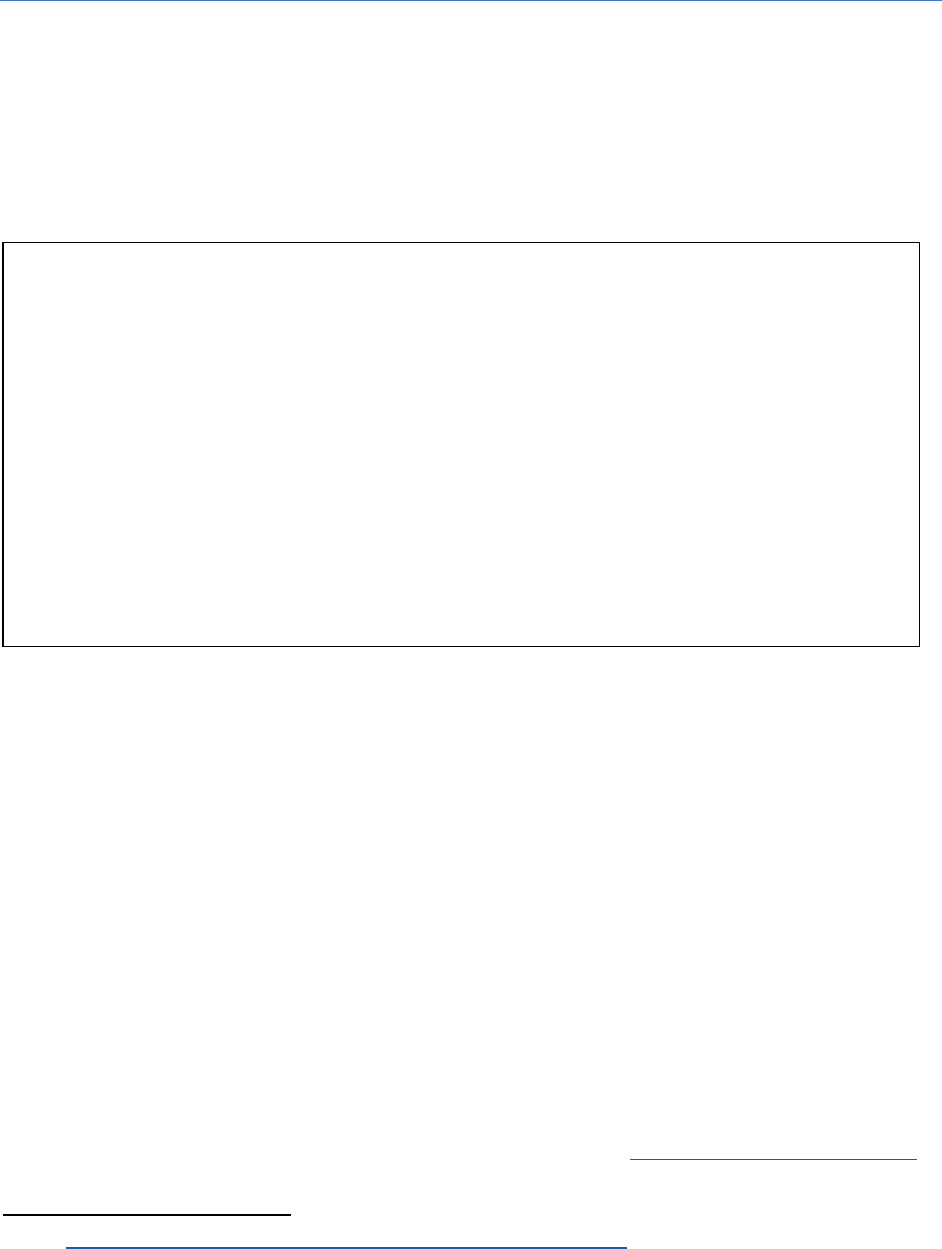

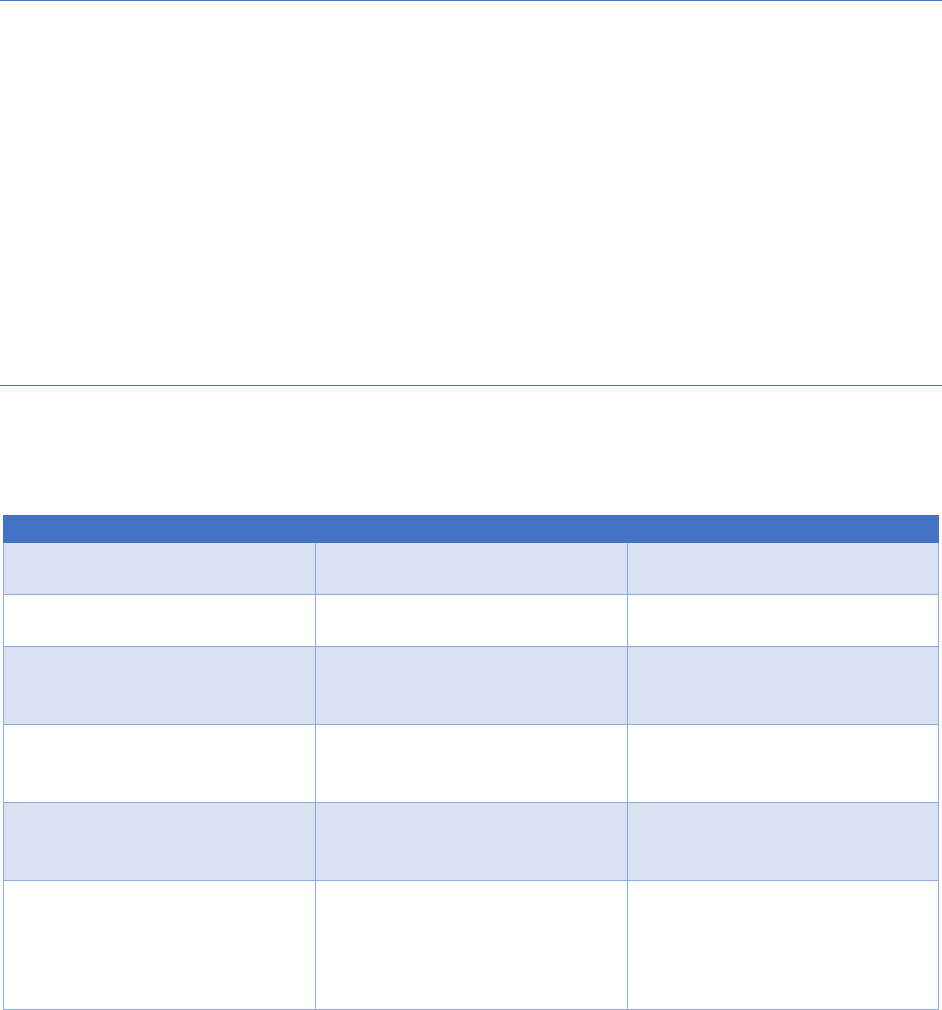

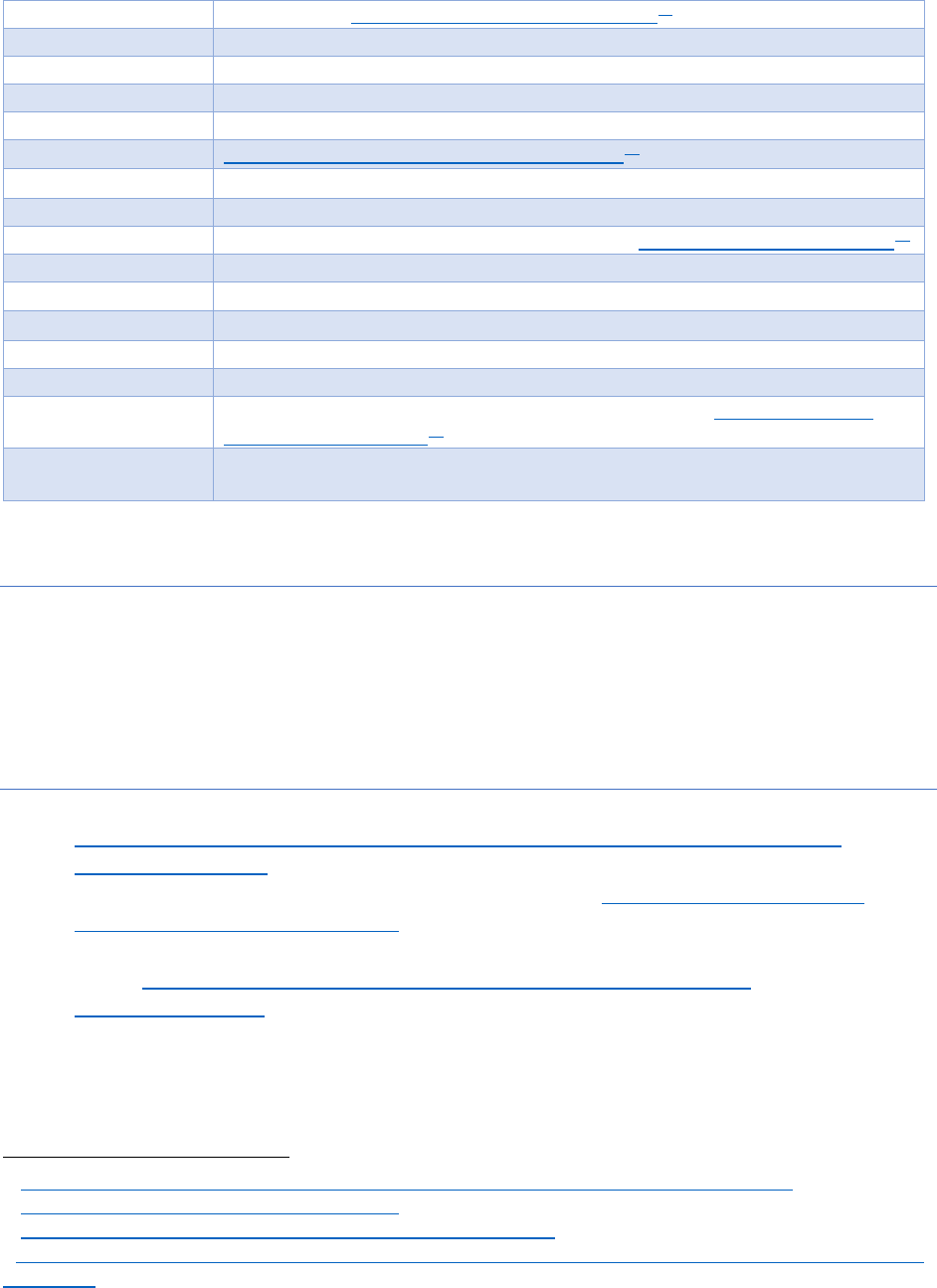

Number of States with Post-Election Audit Laws in 2020

States use a variety of post-election audit methods, including procedural, traditional, risk-limiting audits

(RLAs) or a combination thereof. Some jurisdictions conduct post-election audits, even when not required.

Audit Type

States

Traditional

Alaska, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida,

Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan,

Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New

York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Utah,

Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin

Risk Limiting

California, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon,

Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Virginia, Washington

None

Alabama, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, New Hampshire, South Dakota

Other

Idaho, North Dakota, South Carolina, Wyoming

Procedural

Arkansas, Indiana, Michigan

3

4

6

14

36

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Procedural

Other

None

Risk Limiting

Traditional

Number of States with Post-Election Audit Laws in 2020

9

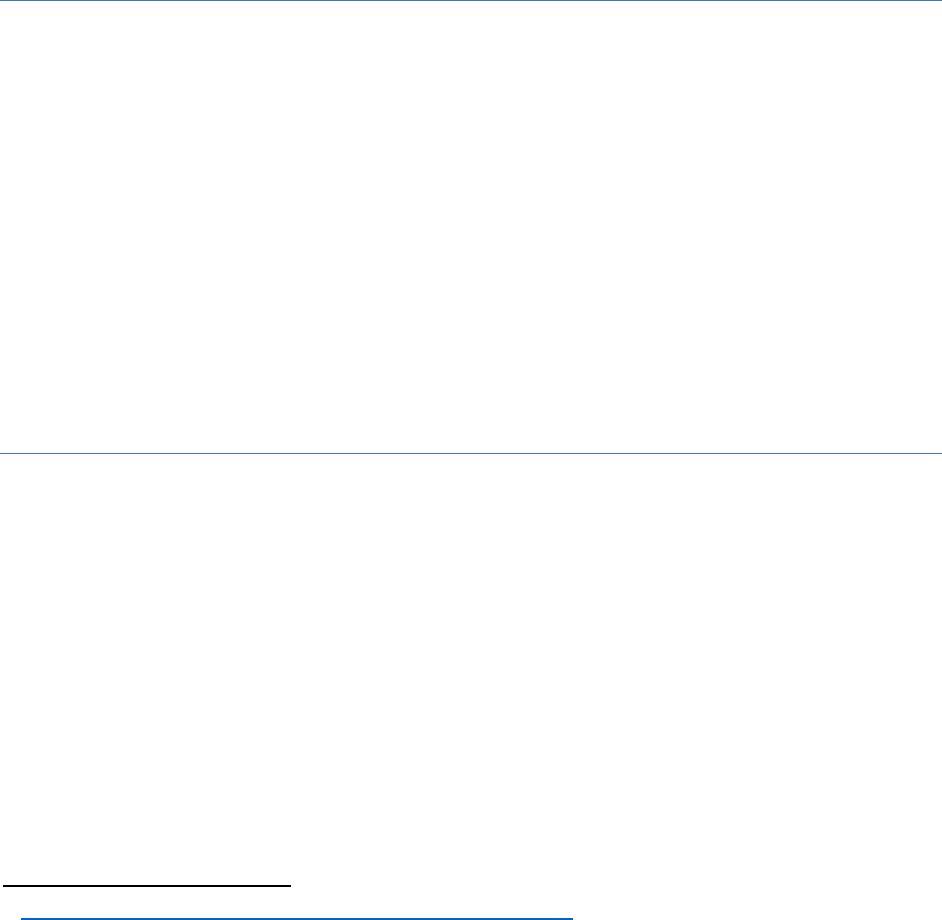

Timing of the Audit

The timing of post-election audits also differs among states. Some states require audits to be completed

before certifying final election results, either before beginning the canvass and prior to the certification

deadline. Other states require election audits after final results have been certified.

Timing

States

Before the Canvass

Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada,

North Dakota, Utah

Before Certification

California, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky,

Massachusetts, Missouri, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon,

Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Washington, West Virginia

After Certification

Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Virginia, Wisconsin

Other

Maryland, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Vermont, Wyoming

10

Traditional Audits

Traditional audits look at a pre-determined number of ballots, voting precincts, or devices and compare

reported results from voting systems to the paper ballot records. State rules or laws determine who conducts

the audit, when the audit occurs, the methodology, and scope.

Fixed Percentage Audits

The most common type of post-election audit is one based on a percentage of precincts. The second most

common type requires a local election official to audit a number or percentage of voting devices. Some states

require a percentage of ballots to be audited. Required percentages range from 1% - 10% or could be

determined for each election by state election officials. In general, a state’s chief election official, an

independent audit board, or local election official randomly selects the precincts, devices, or ballots subject

to the audit, according to a pre-determined formula. A state may determine if all contests or only specific

contests on a ballot need to be recounted.

Once the specific ballots have been identified, an audit board tabulates the selected ballots, and the results

are compared to the reports issued from the voting system. If there is a discrepancy between the two, a state

may require additional ballots to be audited. The audit is considered complete if there are minimal or no

discrepancies, and election officials are satisfied that voting systems accurately tabulated ballots.

Sample Sizes

A variety of methods are used to determine audit sample sizes for traditional audits. Most states that use

traditional post-election audit methods can be broadly categorized as follows:

• Fixed Percentage Determined by State Law. These states will have the minimum percentage of

precincts, devices, or ballots set by statute and will not change unless state law is amended.

• Determined by State Election Official. In these states the chief election official is responsible for

determining the post-election audit procedures.

• Variable or Variable Fixed Percentage. These states will usually have either a fixed percentage that

varies with population size or some other formula. For example, Montana requires an audit of at

least 5% of the precincts in each county or a minimum of one precinct in each county, whichever is

greater; and the audit must include an election for one federal office, one statewide office, one

legislative office, and one ballot issue.

• Fixed Number of Precincts. These states have set a fixed number of precincts to be audited, instead

of a percentage of precincts. For example, Delaware requires an audit of all results of one election

district in each county and one election district in the city of Wilmington. A second option is to

randomly select a statewide race in one election district in each county and one election district in

the City of Wilmington.

• Other. These states will either have a fixed percentage of ballots cast, a minimum number of ballots

required to be audited, or another post-election requirement unique to the state. An example is

Pennsylvania which requires an audit of either 2% of ballots cast in each county or 2,000 ballots,

whichever is less. This category also includes states with different auditing requirements based on

the type of ballots cast (e.g., early voting or by mail) or depending on the type of election.

11

Many jurisdictions will audit more than the minimum percentage required. This could either be by the

discretion of election officials, triggered by contest margins or the percentage of precincts or devices in

smaller jurisdictions will be statically higher than the minimum required. For example, if a county only has 20

precincts and is required to audit 1% of them, it would be statistically equivalent to auditing 5% of precincts.

The map below displays the different types of audits based on the percentage of precincts within these broad

categories, but there are nuances in how every state selects sample sizes.

State

Other

Alaska

*1% from each Congressional district that accounts for at least 5% of ballots cast.

Arizona

*2% of precincts or two precincts/vote centers, whichever is greater for regular

ballots. 1% of ballots cast or 5,000 ballots, whichever is less, and up to 400 ballots for

each machine, including at least one accessible device, for early ballots.

Maryland

*At least 1% of ballot cast.

Pennsylvania

*2% of ballots cast in each county or 2,000 ballots, whichever is less.

Utah

*Vote-by-mail counties audit 1% or 1,000 mail ballots, whichever is less. Batches to

be audited are randomly selected by the Lt. Governor’s Office (LGO). One accessible

voting machine per 100 deployed in every Utah Congressional district, selected

randomly by the LGO, is audited.

12

Contests Included

The contests included in traditional post-election audits vary widely, with most states using unique

methodologies. The most common method requires auditing some statewide contests and at least one other

type of contest, such as a local office or ballot measure. The second most common method is for election

officials to audit every contest on the ballots selected for the audit. Iowa and Tennessee require an audit of

the Presidential or gubernatorial contest, depending on which race is on the ballot. Variations include

combinations of federal, statewide, and local contests, a minimum number of races, or vary with the type of

election.

Contests included in the Audit

State

Statute does not specify

Alaska, Arkansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Oklahoma,

Virginia

Some statewide and some other

contests are audited

Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of

Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas,

Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri,

Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio,

Oregon, Rhode Island, Texas, Washington

All statewide contests are eligible to be

audited, but no other contests

Georgia, New Mexico, Wisconsin

Pre-specified statewide contests are

audited

Iowa, Tennessee

Every contest and ballot issue on the

ballot is audited

California, Indiana, Nevada, New York, Pennsylvania,

Utah, Vermont, West Virginia

0 5 10 15 20 25

Every contest and ballot issue on the ballot is audited

Pre-specified statewide contests are audited

All statewide contests are eligible to be audited, but no

other contests

Some statewide and some other contests are audited

Statute does not specify

Contests Included in the Audit

13

Automated Audits

Traditional post-election audits are usually conducted by hand tallying a sample of paper records and

comparing the results to electronic reports produced by voting systems. However, hand counting can be

expensive, time-consuming, error prone, labor-intensive. To create efficiencies in the process, some states

allow the audit to be conducted electronically. For example, in Hawaii, the chief election official and a

bipartisan team have the option to retabulate 10% of precincts with their voting system as a part of their

post-election audit.

Another type of machine-assisted audit is known as a transitive audit. Transitive audits digitally scan the

ballots using a different voting system or tabulator, other than the primary voting system and compare the

two systems’ results. If both systems report the same winner(s), it provides evidence that the outcome is

correct, even if there are some discrepancies. For example, Florida election officials have the option to

conduct an independent automated audit, which involves using independent hardware and software

technology to tally votes cast across every race that appears on ballots in at least 20% of precincts chosen

randomly.

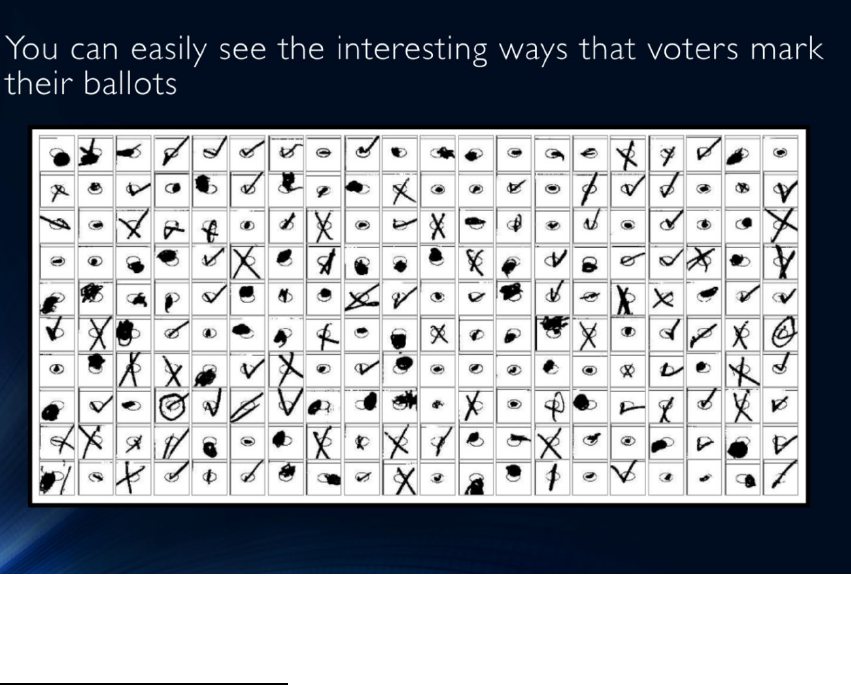

Below is an example of how automated software visually displays ballots with an undervote, overvote to

review voter intent and identify poorly marked ballots not tabulated.

11

. This also serves the dual purpose of

improving training for election officials to instruct voters on how to properly mark their ballots and helping to

identify tabulators that may need to be adjusted or cleaned if the images are crooked or misreading voter

intent.

11

14

Although automated audits can reduce costs and improve the efficiency of post-election audits, there are

important factors election officials consider when using this audit method. Using the same equipment to re-

tabulate ballots may not reveal programming or tabulation errors in the voting system.

Case Study of Maryland State Board of Elections Tabulation Audit

Following the April 2016 Primary Election in Carroll and Montgomery Counties, the Maryland State Board

of Elections conducted a pilot post-election tabulation audit. According to the audit report issued, the

pilot program’s goal was to evaluate feasible post-election tabulation audit methods and based on the

pilot jurisdictions’ experiences, to select the most cost-effective, efficient, and accurate audit method for

use after the November 2016 General Election.

The pilot program used three post-election audit methods:

1. Retabulating all ballot images using an independent third-party technology company

2. Identifying patterns in the ballot images of improper ballot marking

3. Identifying devices with crooked or low-resolution ballot images

Election officials could then use this information to improve poll worker training materials and voter

instructions.

Following this successful pilot program, the Maryland Legislature passed House Bill 1278 which

established a legal post-election audit requirement for the State of Maryland. This bill required both

automatic audits of ballot images as well as manual post-election tabulation audits. After the 2018

General Election, the Maryland State Board of Elections contracted with an independent auditor to

retabulate all of the ballot images from the election. This audit reviewed 11.5 million ballot images which

contained 693 individual contests. Among these contests, only 18 had a vote total difference of any size.

If a contest were found to vary from the previously reported totals by more than 0.5%, then an additional

audit would be conducted; however, none of the contests from this election reported a variance of 0.5%

or greater.

More information about Maryland’s pilot audit program, dated October 2016, can be found here:

https://elections.maryland.gov/press_room/documents/Post%20Election%20Tabulation%20Audit%20Pil

ot%20Program%20Report.pdf

A full report from Maryland’s official 2018 General Election audit, dated May 6, 2019, can be found here:

https://www.elections.maryland.gov/voting_system/documents/2018%20Post%20Election%20Tabulatio

n%20Audit%20Legislative%20Report.pdf

15

Risk-Limiting Audits

In 2010, the EAC made grant awards available to county and state organizations to support research,

development, documentation, and dissemination of a range of procedures and processes for managing and

conducting high-quality pre-election audits, logic and accuracy testing and post-election audit activities. Since

then, many states and jurisdictions have implemented RLAs, either as an alternative to traditional post-

election audits or as pilot programs.

RLAs are based on statistical methods and use specific terminology.

• Ballot manifest - A catalog prepared by election officials listing all the physical paper ballots and

their locations in sequence. This is a requirement for a Risk Limiting Audit but can be used to track

ballot inventory and create an audit record for other types of audits.

• Cast Vote Record (CVR) - Permanent record of all votes produced by a single voter whether in

electronic, paper, or other form. Also referred to as ballot image when used to refer to electronic

ballots.

• Seed - means a number consisting of at least 10-20 digits used to generate a random number

sequence to select ballot cards for audit.

• Risk limit - The largest statistical probability that, if an outcome is wrong, the RLA does not correct

that outcome. For example, assume the reported outcome of an election contest is wrong, and the

risk limit for the audit is 5%. In this instance, there is at most a 5% chance that the audit will not

correct the wrong outcome, and at least a 95% chance that the audit will correct the wrong

outcome. The risk limit is a number between 0 and 1 that limits the risk of certifying an incorrect

outcome and is chosen by the RLA administrative authority before the audit is conducted.

Ballot Polling Audits

A ballot polling RLA is similar to an exit poll, except that ballots, instead of people, are randomly selected and

tabulated (polled). These audits require minimal set-up costs, can be conducted independent of voting

system data, and offer an efficient way to audit contests with 10% or greater margins. Depending on the

number of ballots to be audited, ballot polling RLAs may require additional human resources and can be

time-consuming for contest margins under 10%. Any jurisdiction that uses paper ballots can conduct a ballot

polling audit, regardless of the type of voting system used.

K-cuts

One variation for selecting ballots is by using a method referred to as sampling with k-cuts. This procedure

eliminates identifying specific ballots in a batch, by performing a k “cut” sequence, like cutting a deck of

cards. In practice, the auditors determine how many times to randomly move a fraction of ballots in a stack

from the top of the batch to the bottom. This can be a preselected number or can be determined randomly

with a multi-sided die. The ballot selected for the audit is the final ballot remaining on the top of the stack

after the cuts have been made. A detailed analysis of the k-cut method appears in Mayuri Sridhar’s Master’s

thesis, and in a publication by Rivest and Sridhar published in 2018:

https://fc19.ifca.ai/voting/program.html.

12

12

Mayuri Sridhar and Ronald L. Rivest. k-cut: A Simple Approximately-Uniform Method for Sampling Ballots in

Post-Election Audits. Proceedings Financial Cryptography, February 2019, Fourth Workshop on Advances in Secure

Voting. https://fc19.ifca.ai/voting/program.html

16

Scales

Scales allow election officials to quickly identify the needed ballots to audit during a ballot polling audit.

Batches of a known size are placed on a precision scale. The number of ballots in the batch is entered on the

scale and, as ballots are removed from the top of the stack, the scale counts down. Ballots are removed until

the desired ballot is reached in the stack, eliminating the need to count each individual ball

ot.

Ballot-level Comparison Audits

For a ballot comparison RLA, individual ballots are randomly selected and compared to the cast vote record

(CVR) for each ballot. A CVR is an export of data from the voting system showing how the voting system

interpreted markings on every ballot. Ballot comparison RLAs require fewer human resources to conduct the

audit, allows the auditor to correct any errors, and are efficient for margins of any size. At the same time,

ballot comparison RLAs depend on a voting system that can produce a CVR. They also require maintaining

ballots in the exact order they are scanned or the labeling of ballots with a unique ballot ID and can be time-

consuming to retrieve specific ballots.

Imprinting a unique ID on ballots improves the efficiency of conducting a ballot comparison RLA, but there

are additional considerations that should be considered when labeling ballots. The unique ID should not be

imprinted on sections on the ballot that will cause the ballot to be unreadable by the ballot scanner. The

unique ID must not be able to tie a ballot back to the voter. Finally, the unique ID should be a field in the cast

vote record. For example, if the unique ID on the ballot is “A-1111,” then the cast vote record should reflect

“A-1111,” not “1111. Due to ballot misfeeds, some ballots will have multiple numbers imprinted on them.

Case Study of Colorado Statewide RLA

Colorado was the first state to conduct a statewide RLA for a live election for the 2017 Coordinated

Election. Fifty-six of the sixty-four counties in Colorado participated. Fifty counties conducted a

comparison RLA (forty-seven completed the audit in the first round and three completed the audit in

the second round). Six counties conducted a ballot polling RLA (three completed the audit in the first

round and three in the second round). Six counties did not have elections and two counties hand-

counted ballots. Since then, Colorado has continued to refine their post-election RLAs procedures and

have been assisting other states with adopting ballot-comparison RLAs.

Case Study of Williams County, Ohio RLA Pilot

In August 2021, the Williams County, Ohio Board of Elections conducted a ballot polling audit pilot. The

pilot used a countywide race with 28-point margin from the November 2020 General Election and a 10%

risk limit. The nearly 19,000 ballots cast were divided into batches of approximately 600 ballots. Three

bipartisan ballot boards using precision scales pulled all of the randomly selected ballots in the course of

a morning. The risk limit was met after one round.

17

Batch-level Comparison

Batch-level comparison audits are similar to traditional tabulation audits but are broken down into smaller

units, or “batches,” of ballots scanned on a particular tabulator. This type of audit requires a voting system

that can produce reports of vote totals by the batches they were scanned in. A batch may consist of all

ballots in a precinct, or only those scanned on particular machines. The votes in each selected batch are

manually tallied and compared to the reported tabulation subtotals for the selected batches. Auditors check

that the batch subtotals — including all batches, not just the selected batches — add up to the reported vote

totals.

Multiple Jurisdictions, Alternative Voting Methods, & Privacy

There are some unique considerations for election officials when considering adopting RLAs.

Multiple Jurisdictions

For the results of an RLA to provide statistically significant evidence that reported outcomes are correct, all

ballots in a contest must be subject to inclusion in the audit. This will require coordination among election

officials to perform RLAs in statewide contests, or those contests that cross jurisdictional boundaries.

Alternative Voting Methods

Alternative voting methods, such as Ranked Choice Voting which allows voters to rank their preference order

of candidates, are increasing across the United States. The complexity of alternative voting methods

introduces new challenges to auditing these elections with RLAs. However, RLAs have been used to audit

plurality, majority, super-majority, multi-winner plurality, and ranked choice voting methods.

Privacy

One challenge of auditing elections is that voters are guaranteed the right to a secret ballot in the United

States. Secret ballots are designed to protect voters’ privacy and strengthen elections against attempts of

intimidation, coercion, and corruption from tactics such as vote buying. As election systems become more

sophisticated, with the ability to provide cast voter records which contain granular details about individual

ballots, it can be challenging for election officials to provide enough transparency to validate election

outcomes, while also maintaining voter privacy. Of particular concern is when rare ballot styles, or ballot

types (e.g., ballots cast on accessible voting devices or provisional ballots), can be traced back to particular

voters.

Case Study of the RLA of Instant Runoff Voting in San Francisco, CA

In 2019, the City and County of San Francisco became the first election jurisdiction to conduct a pilot RLA

on an Instant Runoff Voting contest. The pilot audited vote-by-mail ballots in the District Attorney’s race.

Although the RLA did not include all ballots in the contest, it did prove the feasibility of using RLAs for

alternative method voting. For more about this pilot RLA, see the final report YOU CAN DO RLAS FOR IRV

dated April 2, 2020: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.00235.pdf

18

Other Types of Post-Election Audits

Tiered Audits

A tiered audit is when the number of precincts or devices to be audited uses a sliding scale based on the

margin of victory. The narrower the margin of victory, the more ballots and machines are audited. The larger

the margin of victory, the fewer ballots and machines are audited. Tiered audits can also include

requirements that if discrepancies are found in the initial round of auditing, an additional percentage of

precincts or devices must be audited.

Bayesian Audits

Bayesian refers to an approach to statistics in which all forms of uncertainty are expressed in terms of

probability. Like an RLA, this auditing method relies on statistical methods to determine if reported election

outcomes are correct. The main difference between methods is that an RLA concludes when a pre-

determined risk limit has been met. A Bayesian audit concludes when it can be ruled out that the reported

outcome will upset the probability that the winner is correct. They are similar in that each requires the audit

to continue up to a full hand count if the risk or probability limit is not met. In practice, a Bayesian audit

requires that a random sample of ballots be manually examined to determine voter intent. Once examined,

the same sample of ballots are randomly reexamined based on a probability formula. The audit is repeated

until the pre-defined upset probability limit.

Bayesian audits are not widely used in elections, but they have been used in some pilot audits. For example,

in 2018, it was used in Marion County, Indiana and in Rochester Hills, Michigan.

13

One advantage of using the Bayesian audit method is that they are compatible with alternative voting

methods such as ranked-choice voting. More information about Bayesian audits can be found in Ronald L.

Rivest’s paper titled B

AYESIAN TABULATION AUDITS: EXPLAINED AND EXTENDED: https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.00528 .

13

See: (http://electionlab.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2018-12/eas-bagga.pdf), accessed on 9/21/2021

Case Study of Ohio’s Tiered Audits

In Ohio, election officials have the option to conduct tiered audits. The chief election officially generally

prescribes the percentages of ballots to be audited. For the 2020 General election, the Ohio Secretary

of State issued a directive that at least one “top of the ticket” contest (i.e., President or Governor), one

statewide contest (chosen at random by the Secretary of State), and one non-statewide contest

(selected by the board of elections) would be subject to the post-election audit. The local jurisdiction

determines if they will audit by precinct, polling location, or individual voting machine. A county is

required to escalate the audit if Its accuracy rate is:

• Less than 99.5% in a contest with a certified margin of over 1%; or

• Less than 99.8% if the contest has a certified margin of less than 1%.

If the accuracy rate is less than 99.5% after the second round of auditing, the county may be required

to do a complete hand count.

19

Independent Audits

First-party audits, or internal audits, occur when they are performed within an organization. Most post-

election tabulation audits are considered first-party because they are conducted by election officials as a part

of certifying election results. Many jurisdictions require citizens of differing party affiliations to convene audit

boards to conduct post-election audits. However, audit boards are still under the supervision of election

officials.

Third-party audits occur when they are performed by independent audit organizations, separate from the

officials who initially completed the work. Third-party audits can be implemented by other government

agencies or by independent organizations. For example, the Secretary of State in Michigan oversees

procedural audits of local election officials, and the Secretary of State in New Mexico hires an independent

contractor to oversee and assist counties with their post-election audits.

State and local election offices have increasingly contracted with organizations, non-profits, and academics

who have professional backgrounds in statistics, data analytics, cybersecurity, or auditing to improve auditing

methodologies. One such example is the Monitoring the Election Project pilot project between researchers at

the Caltech/MIT Voting Technology Project, the Orange County California Registrar of Voters (OCROV) office,

and the John Randolph Haynes Foundation in 2018.

14

In this pilot project, for both the 2018 primary and

general elections in Orange County, the team built and implemented several different performance

methodologies:

1. Mail ballot transmission and return tracker

2. In-person observation studies of early and Election Day voting

3. Post-election precinct-level turnout. candidate forensics and anomaly detection analytics

4. Post-election voter surveys (general election)

5. Voter registration auditing

6. Observation and study of OCROV’s post-election risk-limiting audits

7. Social media monitoring

Through this partnership, improved auditing methodologies were developed, and actionable performance

measurements were identified. Reports and summaries are available on the project’s website:

https://monitoringtheelection.us/

After the 2020 election cycle, several state legislatures have pursued independent or third-party audits of

election results. Some notable examples include the Arizona State Senate President issuing a subpoena to

audit election records in Maricopa County and the New Hampshire State Legislature passing Senate Bill 43

14

See: https://monitoringtheelection.us/ , accessed 9/10/2021

Case study of Vermont Independent Post-Election Tabulation Audits

In Vermont, elections are administered by Town Clerks with general oversight from the Secretary of

State. Within 30 days of an election, the Secretary directs town officials to transport select ballots to the

office of the Secretary of State. The Secretary then conducts the audit using equipment that is

independent of the tabulators originally used to count ballots by the Town Clerks. The Secretary then

publicly announces the results of the audit.

20

(2021) to require an independent audit of the State Representative contest in Rockingham County District 7

(the Town of Windham).

When election systems are audited or examined by third parties, clear procedures for ensuring the chain of

custody is not broken are critical to avoid risks related to the voting system’s confidentiality, integrity, and

availability. The EAC published a comprehensive Chain of Custody Best Practices guide, with additional

guidance for working with third parties:

https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/bestpractices/Chain_of_Custody_Best_Practices.pdf

Procedural Audits

Audits conducted to determine if election procedures are followed are often referred to as procedural,

performance, process, or compliance audits. These audits include ensuring that forms are signed, vote

tabulation equipment is tested, ballot materials are securely sealed, and the custody of critical election

materials is documented. Some jurisdictions reconcile voter registration records and associated voting credit

with the number of ballots cast as a part of their procedural audit. For example, Florida has a post-election

reconciliation statute and rule that requires voter registration information and information about who voted

in the election to be compiled and a report issued within 30 days after the election results are

certified.

15

Procedural audits have some similarity with the “canvass.” During the canvass, election officials

reconcile the number of provisional, early, and in-person ballots cast with the number of voters who signed

poll books. The purpose of the canvass is to make sure that every valid vote is included in the final results. In

2018, the EAVS Policy Survey collected comprehensive data about post-election audits requirements in

states. Although 16 states reported requiring some form of procedural audit, it is unclear if the states

reported these activities as a part of the canvass or a separate procedural audit. According to the 2018 EAVS

report, the following 16 states reported that a procedural audit was required:

16

State

State Requires Procedural Audit

Alaska

Every election

Arizona

Every election

Hawaii

Every election

Iowa

Under certain conditions

Maryland

Every election

Michigan

Every election

Mississippi

Every election

New Hampshire

Every election

Puerto Rico

Every election

South Carolina

Under certain conditions

Tennessee

Every election

U.S. Virgin Islands

Every election

Washington

Every election

West Virginia

Under certain conditions

Wisconsin

Every election

Wyoming

Under certain conditions

15

. F.S. 98.0981 and Rule 1S-2.053(7), DS-DE 141 SOE guide to Division of Elections.

16

2018 EAVS

21

Project Management Planning

In some states, audit procedures and standards are required to be published well in advance of an election.

Planning for a post-election audit helps set expectations and timelines. Examples of project management

plans include:

• A workflow diagram for officials conducting the audit.

• A checklist of tasks to be accomplished during the audit.

• Rigorous security and chain of custody procedures, including sign-in/out logs and a security video.

• Identification badges for everyone present at the audit.

Case study of Michigan Procedural Audits

Michigan began conducting post-election audits in 2013. The audit process begins as a review of

administrative procedures.

Michigan is one of several states with a highly decentralized election system. Local city and township

clerks are responsible for registering voters, hiring poll workers, and issuing ballots to voters. County

clerks are responsible for programming voting equipment, printing ballots, and training poll workers at

the county level. County clerks are also responsible for conducting post-election audits. Because of

Michigan’s decentralized system, county clerks are responsible for auditing the work of their local

counterparts.

As part of Michigan’s procedural audits, the local clerks selected for the audit must produce

documentation showing that key pieces of the electoral process were completed. These include several

categories of items that are reviewed:

• Poll Workers:

o Poll workers attended training and received a training certificate.

o Poll workers were appointed by the local Election Commission to serve during the

election.

o Each of the two major parties was represented in the precinct, and that all poll worker

party affiliation was shared with county-level political parties.

• Election Technology:

o Electronic poll book was properly downloaded and installed on Election Day.

o Voting equipment was tested correctly and functioning before the election.

• Paper Documentation:

o Each voter appeared on the list of voters and has a ballot application on file (both in-

person and absentee voters).

o Chain of custody certificates have been signed by members of the two major political

parties, and all seal numbers have been properly recorded.

• Ballot Review:

o Adequate accounting of provisional ballots.

o Ballots that required duplication (typically mailed-in ballots unable to be scanned) were

duplicated correctly.

o The total number of votes cast in specific contests matches the official canvass results

in those contests.

22

• Procedures for sorting ballots, if required by state statute or regulation.

• Tally sheets used in the audit, if required.

• Procedures to address and explain discrepancies, if found.

Elections are typically funded at the local level, which determines staffing levels, voting equipment, or

software tools available to perform the audit function. Budgets and resource management will factor into

each election jurisdictions’ project planning process.

Training

Successful implementation of any process involves robust training. Procedures for conducting post-election

audits will vary from small to large jurisdictions. Lessons learned from states who have implemented new

post-election audit requirements include providing training to local election officials, considering differences

in budget, staffing, number of ballots, voting system, storage, and tabulation facilities. In addition, following

each audit, officials routinely evaluate whether processes could be improved in future elections.

Hands-on practice is an effective training method. Observing audits in other jurisdictions is one method

election officials have successfully used to become familiar with new audit methods. Participating in or

observing mock and pilot audits can help election officials understand new procedures in a learning

environment where it is safe to make mistakes. This way, election officials can prepare, a before adopting

new protocols, to successfully perform an audit under real-world pressure.

Voting Systems

The type of voting system used in a jurisdiction can affect post-election audit capabilities. Some states use a

single vendor voting system, but most states allow their local jurisdictions to use one of a variety of state-

approved voting systems. Following are the types of voting systems currently certified by the EAC and the

types of post-election audits methods each system supports.

Voting System

Ballot Record Type

Audit Methods

Hand Count

Voter marked paper ballot

Procedural, Traditional, Risk

Limiting

Hand Marked Paper Ballots, with

Scanner

Voter marked paper ballot

Procedural, Traditional, Risk

Limiting, Automated

Ballot Marking Device, with

Scanner

Voter marked electronic ballot

that produces a paper record of

the vote selections

Procedural, Traditional, Risk

Limiting, Automated

DRE with VVPAT

Voter marked electronic ballot

with vote selections recorded on

VVPAT and memory card

Procedural, Traditional, Risk

Limiting

DRE without a Voter Verified

Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT)

Voter marked electronic ballot

with votes recorded on memory

card

Procedural

Uniformed and Overseas Civilian

Act (UOCAVA) and Remote

Accessible Voting by Mail

(RAVBM)

Ballots which are duplicated at

the local election official’s office

Procedural (Once duplicated,

these ballots are tabulated with

other paper ballots and are

included in regular post-election

audits)

23

Tabulation Environment

The type of tabulation environment a jurisdiction uses will affect post-election audit capabilities. Vote

tabulation occurs at a central count location (usually a local election official’s office/facility), polling place or

vote center, or a combination of both.

• Central Count Environment – Voted ballots are placed in secured ballot boxes and are transported to

a central location to be tabulated by election officials.

• Precinct Count/Vote Center Environment - Ballots are tabulated on DREs or scanning devices at the

polling location, and results are transmitted to election officials at the end of the voting period.

Independent Software Systems

Traditional hand tally and procedural audits do not require the use of independent software systems. Some

aspects of a procedural audit may rely on software independent audit tools if they require verifications, such

as whether audit logs were altered.

Conducting small RLAs entirely by hand may be possible, but most jurisdictions will need to acquire a

software system for RLAs. These systems are used to calculate the risk limit, generate the list of ballots

selected for the audit, capture human interpretations of voter intent, and compare machine and human

interpretations of election results.

There are several open-source repositories of RLA software. However, software options may be regulated by

state rules or laws. All voting systems certified by the EAC need to be software independent to conform to

the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG). Software independence means that an undetected error or

fault in the voting system’s software is not capable of causing an undetectable change in election results.

There are two essential concepts behind applying software independence:

• It must be possible to audit voting systems to verify that ballots are being recorded correctly; and

• Testing software is so difficult that audits of voting system correctness cannot rely on the software

itself being correct.

Cybersecurity

Election officials utilize a variety of methods to prevent administrative errors and to defend against cyber-

attacks. Rigorous post-election audits are one way to mitigate cyber-threats. While audits cannot prevent

attacks on voting systems, post-election audits can reveal if a breach or administrative error occurred.

Alternatively, audits can also provide strong evidence that voting systems were secured if the election results

are challenged.

Security

Nearly 90% of Americans voted on paper ballots in 2020. Ballots and ballot paper stock are highly regulated,

with some states requiring additional security measures such as serial numbers or watermarks, and they are

tracked from the time they are received, throughout the election process. Prior to an audit, ballots are stored

in sealed containers and kept in a secured area with restricted access. Examples of steps incorporated into

audit security plans include:

• Two or more staff members overseeing the transfer of ballots to and from the audit location.

24

• Securing additional election materials–including memory cards, rosters, etc.–needed for the audit.

• Using a check-in/out system for ballots during the audit, with the audit teams signing and indicating

time of taking and returning each batch.

• Audit teams documenting the number of ballots removed and replaced in each ballot box.

• Clear instructions of who may touch ballots during the audit and boundaries marked for observers.

• Video monitoring.

• For a multi-day audit, planning to either move ballots back to secured storage locations at the end of

each day or securing the ballots and equipment at an auditing location.

• At the conclusion of the audit, ensuring all ballots are resealed in their containers for transportation

back to the secured storage location.

Transparency

Transparency can be the key to a successful post-election audit. Many states require post-election audits to

be conducted in public. Some states like Minnesota allow observers to verify marks on ballots, so that

observers can verify audit conclusions. Examples of transparent audit procedures include the following:

• Distributing information on voter intent laws to those conducting the audit and to observers.

• Providing copies of any rules and regulations for the conduct of observers.

• Distributing chain of custody procedures used in the audit.

• Distributing materials explaining any rules on the use of cellphones, audio, or video recording.

• Developing written procedures for addressing discrepancies and if additional targeted samples

must be counted.

• Posting final results promptly and transmitting the results to state election officials, if required.

• Communicating the results of the post-election audit to the media.

• Issuing a report including an analysis of any discrepancies and recommendations for

improvement.

Legal Considerations

The applicable laws, regulations, and procedures in a jurisdiction are the framework for what is required or

allowed in a post-election audit. Some states allow flexibility in determining what and how elections can be

audited or if parallel and pilot audits can legally be performed.

Federal law

There is no federal law requiring election audits in the United States. However, some federal laws that

impose constraints on the destruction of election materials with which every jurisdiction must comply, are

outlined in F

EDERAL LAW CONSTRAINTS AND POST-ELECTION “AUDITS” a document published by the U.S.

Department of Justice on July 28, 2021.

17

State law will restrict or authorize who has access to local election

materials post-election for audit purposes.

17

https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1417796/download

25

State Law

Below is a reference key of individual state laws in effect at the time of publication.

State

Post-Election Audit Laws

Alabama

N/A

Alaska

Alaska Stat. §15.15.420, §15.15.430, §15.15.440, §15.15.450, §15.10.170

Arizona

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §16-602 State of Arizona Elections Procedures Manual

18

Arkansas

Ark. Code § 7-4-101, § 7-4-121, § 7-5-702

California

Cal. Elec. Code §336.5, §15360, §15365 et seq. (West 2015)

Colorado

Colo. Rev. Stat. §1-7-515 Colo. Sec. of State Election Rule 25

19

on risk-limiting

audits. Colo. Sec. of State Election Rule 8

20

on watchers.

Connecticut

Conn. Gen. Stat. §9-320f

Delaware

Del. Code. Title 15 § 5012A

District of Columbia

D.C. Code Ann. §1-1001.09a

Florida

Fla. Stat. Ann. §101.591

Georgia

Ga. Code Ann. §21-2-498

Hawaii

Hawaii Rev. Stat. §16-42, Haw. Admin. Rules § 3-172-102

Idaho

Idaho Code §34-2313

Illinois

Il. Rev. Stat. Ch. 10 §5/24A-15, Ch. 10 §5/24C-15

Indiana

Indiana Code, §3-12-13, §3-12-14, §3-12-3.5-8

Iowa

I.C.A. § 50.51

Kansas

K.S.A. 25-3009

Kentucky

Ky. Rev. Stat. §117.383 §117.305 §117.275(9)

Louisiana

N/A

Maine

N/A

Maryland

Code of Md. Regs. §33.08.05.00 et seq., Md. Election Law §11-309

Massachusetts

Mass. Gen. Law Ann. Ch. 54 § 109A

Michigan

M.C.L.A. § 168.31a Post-Election Audit Manual

21

(2018)

Minnesota

Minn. Stat. Ann. §206.89

Mississippi

N/A

Missouri

15 Mo. Code of State Regs., §30-10.090, §30-10.110

Montana

Mont. Code Ann., §13-17-501 -§13-17-509

Nebraska

Not required by statute

Nevada

SB 123

22

(2019) Nev. Admin. Code 293.255

New Hampshire

N/A

New Jersey

N.J. Stat. Ann. §19:61-9

New Mexico

N.M. Stat. Ann. §1-14-13.2 et Seq., N.M. Admin. Code 1.10.23

New York

N.Y. Election Law § 9-211 (McKinney 2015), 9 N.Y. Comp. Rules & Regs. 6210.18

North Carolina

N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann. §163-182.1

North Dakota

N.D. Cent. Code 16.1-06-15

18

http://live-az-sos.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2018 0330 State of Arizona Elections Procedures

Manual.pdf

19

https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/rule_making/CurrentRules/8CCR1505-1/Rule25.pdf

20

http://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/rule_making/CurrentRules/8CCR1505-1/Rule8.pdf

21

http://www.michigan.gov/documents/sos/Post_Election_Audit_Manual_418482_7.pdf

22

https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/80th2019/Bill/6130/Text

26

Ohio

R.C. 3505.331, Secretary of State Directive 2019-30

23

Oklahoma

Okla. Stat. §26-3-130

Oregon

Or. Rev. Stat. §254.529, §254.535

Pennsylvania

Pa. Cons. Stat. tit. 25 §3031.17 §2650

Rhode Island

§ 17-19-37.4

South Carolina

Description of Election Audits in South Carolina

24

South Dakota

N/A

Tennessee

Tenn. Code Ann. § 2-20-103

Texas

Tex. Election Code Ann. §127.201 (Vernon 2015) Election Advisory No. 2012-03

25

Utah

Election Policy Directive, Utah Code Ann. §20A-3-201

Vermont

17 Vt. Stat. Ann. §2493, §2581 - §2588

Virginia

Va. Code § 24.2-671.1

Washington

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §29A.60.185, §29A.60.170, Wash. Ad. Code 434-262-105

West Virginia

W. Va. Code, §3-4A-28

Wisconsin

Wis. Stat. Ann. §7.08(6), Wisconsin Elections Commission 2018 Post-Election

Voting Equipment Audit

26

Wyoming

W.S. 22-11-104, Wyo. Admin. Rules Secretary of State Election Procedures

Chapter 25

Conclusion

Post-election audits are routinely performed by a majority of states. RLA pilot programs are also becoming

more common. The way that each state conducts post-election audits vary significantly. These variations

provide a wealth of information that can be analyzed and inform election officials, researchers, and

policymakers when considering adopting new post-election audit procedures.

Additional Resources

• NASS Task Force on Voter Verification: Post Election Audit Recommendations Report:

https://www.nass.org/sites/default/files/Summer 2021/NASS Vote Verification Task Force

Recommendations.pdf

• EAC webpage dedicated to post-election audits and recounts: https://www.eac.gov/election-

officials/post-election-audits-recounts

• National Conference of State Legislatures webpage on post-election

audits: https://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/post-election-

audits635926066.aspx

23

https://www.ohiosos.gov/globalassets/elections/directives/2021/eom/eom_ch09_2021-02.pdf

24

https://www.scvotes.org/data/AuditDesc.html

25

http://www.sos.state.tx.us/elections/laws/advisory2012-03.shtml

26

https://elections.wi.gov/sites/default/files/memo/20/commission_sep_25_meeting_audit_decision_10_01_18_

_29601.pdf